When the Watchdog Lost Line-of-Sight

A story about the Fourth Estate, the feed, and the new architecture of persuasion.

I remember the old habit of choice as something physical.

A newspaper had weight. A TV channel had a number. Even the act of turning a page or switching a remote carried a small democratic meaning: I was selecting my gatekeeper. I might have been selecting bias, ideology, or class, but I was selecting it knowingly. If I wanted to challenge my own intake, I could buy a different paper. I could watch a different bulletin. I could argue with an editorial line because I could see it.

Then the front page disappeared.

Not in the sense that journalism vanished, but in the sense that the public square stopped being shared. The news became a feed. The gate stopped being a door and became a current. And somewhere inside that current, the watchdog of democracy, the press, lost something it had always depended on: line-of-sight.

The Fourth Estate is not “the truth.” It is visibility.

We often describe the media as a “fourth power,” a Fourth Estate, a watchdog that balances the state. That framing can sound ceremonial, like an old constitutional decoration. But it describes a very practical function: public visibility.

The press does not have to be perfect to be useful. It does not even have to be neutral. What it must do is make power legible: who decided what, who benefited, who lied, who hid, who paid. It creates a record. It puts actions into a shared space where they can be challenged.

Democracy is not built on omniscience. It is built on the assumption that citizens can see enough of the same world to judge it together. That overlap, the common file, is the oxygen.

In the old media era, the public sphere was flawed but legible. The errors were visible. The incentives were imperfect but knowable. And crucially, everyone could point to the same front page and argue about it.

The old bargain: biased, but auditable

Yes, there were monopolies. Yes, there were propagandists. Yes, there were owners with interests. But the architecture of persuasion had a particular shape.

It was public.

When a politician lied on television, the lie happened in the open. When a newspaper ran a slanted story, it was printed for all to see. When an editor pushed a narrative, that narrative could be contested because it had a clear source and a stable form. You could quote it. You could archive it. You could hold someone accountable to it.

Even the most partisan station still broadcast one program at a time. You could accuse it of bias because you could identify the thing you were accusing.

The watchdog, for all its flaws, had line-of-sight.

The new bargain: personalized, but unknowable

Social media did not eliminate choice. It reframed it.

You still “choose” what to follow. You choose a few friends, a few accounts, a few topics. But the decisive choices, the choices that shape reality, sit elsewhere:

- what appears first

- what gets repeated

- what is recommended

- what is quietly suppressed

- what is amplified into the millions

In the feed, the editor is not a person. It is a function.

And that function is rarely optimized for civic clarity. It is optimized for attention.

That is not a conspiracy. It is a business model. Engagement is the currency. Time is the product. And the most reliable way to win time is to trigger emotion: anger, fear, indignation, tribal belonging, humiliation, outrage. These are not moral judgments. They are predictable human reactions.

Once you accept that, the rest becomes easier to understand. Manipulation does not require mind control. It requires architecture.

Want the full evidence base and EU policy details? Download the full report:

A feed is not a list. It is a hierarchy.

Two people can follow the same accounts and live in different realities because what they receive is ordered differently, repeated differently, and surrounded by different “context.” One person sees politics every day and believes society is collapsing. Another sees lifestyle content and believes nothing is happening. Same city. Same week. Different weather systems.

In the old world, agenda-setting was public. In the feed, agenda-setting becomes private. You are not only consuming content. You are consuming a decision about what matters.

When order is personalized, reality becomes negotiable.

In a feed economy, the most contagious content is not always the most accurate. It is the most reactive.

A calm correction is boring. A misleading clip is electric. A careful explanation loses to a confident accusation. Even if you never share falsehoods, you still participate in their advantage if you pause longer on them, comment on them, quote them to debunk them, or screenshot them to complain about them. Attention is counted even when it is angry.

This creates a distortion that looks like “public opinion” but is often just “what the system found to be sticky.” Visibility becomes mistaken for importance.

In this world, the market price of attention is often paid in truth.

The feed is not only algorithmic. It is social.

We trust things not because they are true but because they arrive through familiar people. A rumor forwarded by a friend does not feel like propaganda. It feels like community. It feels like “people are talking about it.” It feels safe.

That feeling is a vulnerability.

If you want to manipulate a person, you do not always try to persuade them directly. You seed their network and let their network persuade them. You do not need a million believers to create a million impressions. You need a few thousand strategically placed accounts and a system that rewards repetition.

In the feed, persuasion is outsourced to friendship.

This is where the old democratic logic breaks most cleanly.

Democracy assumes that politics is a public argument. You make claims in the open, opponents challenge them, journalists test them, citizens judge them. That is the point of the public square.

Microtargeting can turn politics into private persuasion.

One group is shown a message about crime. Another is shown a message about climate. Another is shown a message about immigration. Each message is engineered for the anxieties of that group. The contradiction between them is invisible because the audience is fragmented. There is no shared record to contest.

A public lie can be corrected. A private lie can scale.

This is not only about foreign interference. Domestic campaigns can do it too. The danger is structural: once political speech becomes individualized at scale, accountability becomes optional.

The most effective influence rarely looks like influence.

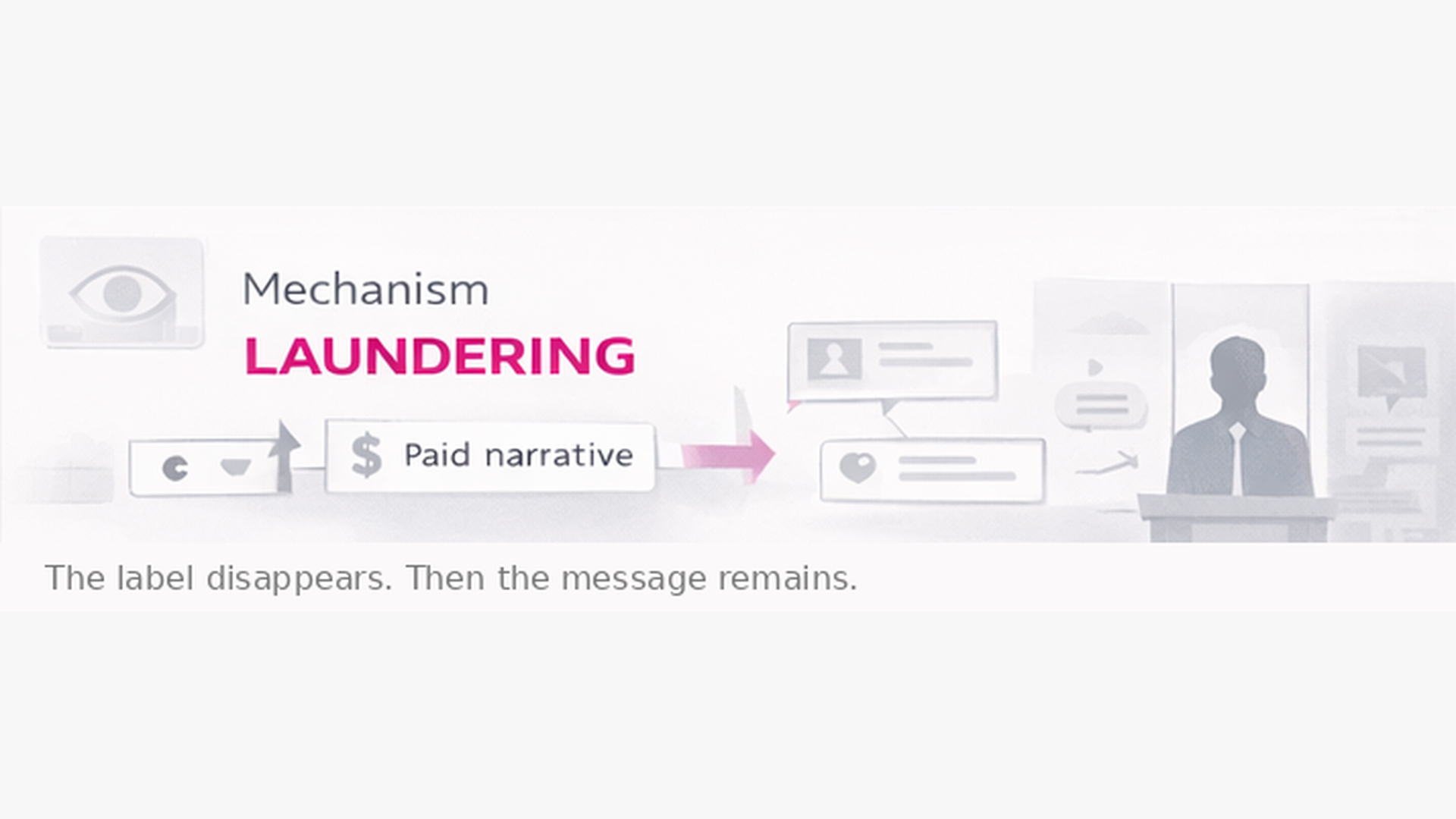

A paid narrative can arrive as an influencer “just asking questions,” as a meme, as a clip stripped of context, as a “leak,” as a screenshot without a source. It can circulate through humor and identity long before anyone argues about facts.

By the time a journalist debunks it, it has already done its work. Not because it convinced you of a specific claim, but because it shifted your mood: cynicism, distrust, disgust, resignation. That mood is politically powerful.

Propaganda works best when it does not look like propaganda.

There is a particular kind of manipulation that does not try to convince you of a claim. It tries to convince you that a claim is everywhere.

A coordinated cluster of accounts can manufacture the feeling of a wave. They can make an idea trend, brigading it with comments and reposts, then point to its visibility as proof of its legitimacy. Journalists cover “the debate.” Politicians respond. The idea becomes real through reaction.

This is how a fringe narrative becomes a national conversation.

Visibility becomes mistaken for popularity, and popularity becomes mistaken for truth.

Now the loop completes.

You watch a clip. You react. The system learns. It gives you more of that category. Your peers, exposed to similar content, share similar signals. The cycle tightens. Over time, your feed becomes not a window but a mirror.

The algorithm does not radicalize by argument. It radicalizes by repetition.

People imagine manipulation as a single moment of deception. In practice, it is often a slow narrowing of what feels plausible.

What this costs: the loss of a shared record

The deepest damage is not that citizens disagree. Democracies can tolerate disagreement. They are designed for it.

The damage is that citizens stop agreeing on what happened.

When each person’s information environment becomes uniquely tailored, the common file dissolves. Accountability weakens. Cynicism rises. The space becomes fertile for two kinds of power:

- the power that lies openly because correction is fragmented

- the power that acts quietly because attention is elsewhere

In this environment, the Fourth Estate struggles not only because it is under pressure, but because it is trying to shout into a room that no longer exists.

The watchdog has not vanished. It has lost line-of-sight.

So what can be done without turning democracy into censorship?

This is where Europe enters the story, not as a legal saga but as an attempt to restore visibility.

The EU’s emerging approach can be understood in three plain goals:

- Make the system legible

If feeds and ads shape reality, citizens should be able to see why something reached them and who paid for it. - Make manipulation harder

Limit the most abusive targeting, especially in politics. Create friction for covert amplification. - Make oversight possible

Give researchers and regulators enough access to test claims, audit systems, and enforce rules with evidence, not vibes.

That is the moral logic. The detailed report you will attach is the machinery.

But the narrative readers need is simpler: Europe is trying to rebuild line-of-sight in a world where persuasion has become individualized, invisible, and scalable.

The citizen’s line-of-sight kit

No regulation will fully solve a cultural and technological transformation. Even the best rules cannot force people to seek nuance. But citizens are not powerless. There are small habits that blunt the mechanisms above.

- Build a pull layer: subscriptions, newsletters, direct sources. Choose inputs deliberately.

- Treat outrage as a “verify” trigger: if something spikes emotion, pause and check the source before sharing.

- Rotate your lenses: one outlet you agree with, one you don’t, one that is boring and factual.

- Use whatever transparency tools exist: “why am I seeing this,” ad labels, topic controls. They are imperfect, but they restore a little visibility.

- Remember the difference between “I saw it” and “it is widespread.” Visibility is not prevalence.

The point is not to become paranoid. The point is to become literate in the new architecture of persuasion.

Because the question that defines our era is not only “what is true?” It is also: who decided what you saw first?

When you cannot answer that, you cannot tell whether you are informed or merely addressed.

And when citizens cannot tell the difference, democracy does not collapse in one dramatic moment. It slowly loses its line-of-sight.