The Boys Who Fell Out of the Story

How loneliness, digital markets, and grievance quietly reshape the politics of young men

Editor's Note

In political economy we tend to tell a familiar story: when unemployment rises, wages stagnate, and inequality bites, extremist movements gain ground. That story is not wrong, but perhaps incomplete.

Over the last few years, a parallel story has emerged from public health. Loneliness is now treated as an epidemic, with evidence that chronic social isolation raises the risk of serious illness and premature death, in some studies rivaling heavy smoking or excessive alcohol use. Men, in particular, report fewer close friendships, more online-only connection, and strong pressure to stay “strong” and unemotional.

This piece asks what happens when those emotional and social pressures intersect with the digital markets that structure young men’s lives – dating apps, social media feeds, and the influencers who offer simple explanations for complex disappointments. It explores how romantic failure, unequal attention markets, and grievance-based narratives can, over time, harden into a distinct pattern of political attraction.

This is not a story about how “incels cause fascism” or “dating apps elect strongmen.” That kind of linear thinking is both wrong and politically dangerous.

Most men who are lonely or frustrated will never become extremists.

Most men who hold sexist beliefs will never commit violence.

Most people who hear a demagogue speak will never storm a building.

The value of following Nate’s trajectory is to trace a contour of:

- unmet expectations about love and status,

- narrative supply – who steps in to explain that disappointment,

- institutional absence – who doesn’t.

We have long accepted that investor panic can destabilize markets, that consumer confidence can prolong a recession, that a story about “everyone else is pulling their money out” can become self-fulfilling.

We are slower to accept that young men’s shifting emotional economies – their mixtures of shame, resentment, and longing – might play a similar role in our democracies.

But the data are starting to point there.

The case studies are starting to point there.

The feeds, if you watch them closely, have been pointing there for a while.

Find out more about what science tells us and what it does not, by reading the full report here:

Prologue

He is not at a rally when our story starts.

He is in his room. The phone screen is inches from his face, the blue light flattening his features into something older and more tired than his 22 years.

Let’s call him Nate.

It is after midnight in a mid-sized Western city. The blur of the day has faded – another shift at the warehouse, another awkward silence on the bus, another swipe session that led nowhere. On Tinder, he has 0 new matches. On Hinge, the app tells him, helpfully, that he has “liked 113 profiles” this week.

No one has liked him back.

So he does what he has started doing most nights: he taps out of the dating apps and into a forum where the tone is different. There, the usernames have harsh, bitter humor – LeftoverGene, FacialWound, BetaGrind. The posts are longer. Men describe their weeks, their face shapes, their loneliness. They complain that women only want “Chads,” that feminism has “broken the market,” that men like them have been “priced out of intimacy.”

Nate reads a long thread titled: “Women ruined dating.”

He nods along. He can feel the anger clarifying into something that feels like understanding.

This is where the story begins – not with mobs and flags, but with a young man alone in his room, looking for a reason why his life feels stuck.

The New Gender Gap: Two Stories, One City

A few miles away, another phone screen glows.

This one belongs to Leah.

She is the same age, in the same city, on the same apps. Her notifications look different. Her problem is not silence but saturation. Every time she opens the app there are new likes, new messages – some sweet, some creepy, many exhausting.

When she scrolls social media, her feed is full of feminism and therapy posts, mutual-aid campaigns, calls for climate marches. Her group chat argues about elections, trans rights, the right to abortion. She has a sense – fuzzy but firm – that progress means moving left: more fairness, more equality, more inclusion.

Nate’s feed, meanwhile, has drifted. It used to be soccer clips and gaming content. Now the “For You” page is threaded with a different tone:

- videos of men warning that “men are under attack,”

- clips of an influencer talking about how “feminism has ruined women,”

- shorts of a muscular man in sunglasses saying that “weak men create bad times.”

Two young adults, same city, same platforms, and their digital realities are no longer overlapping.

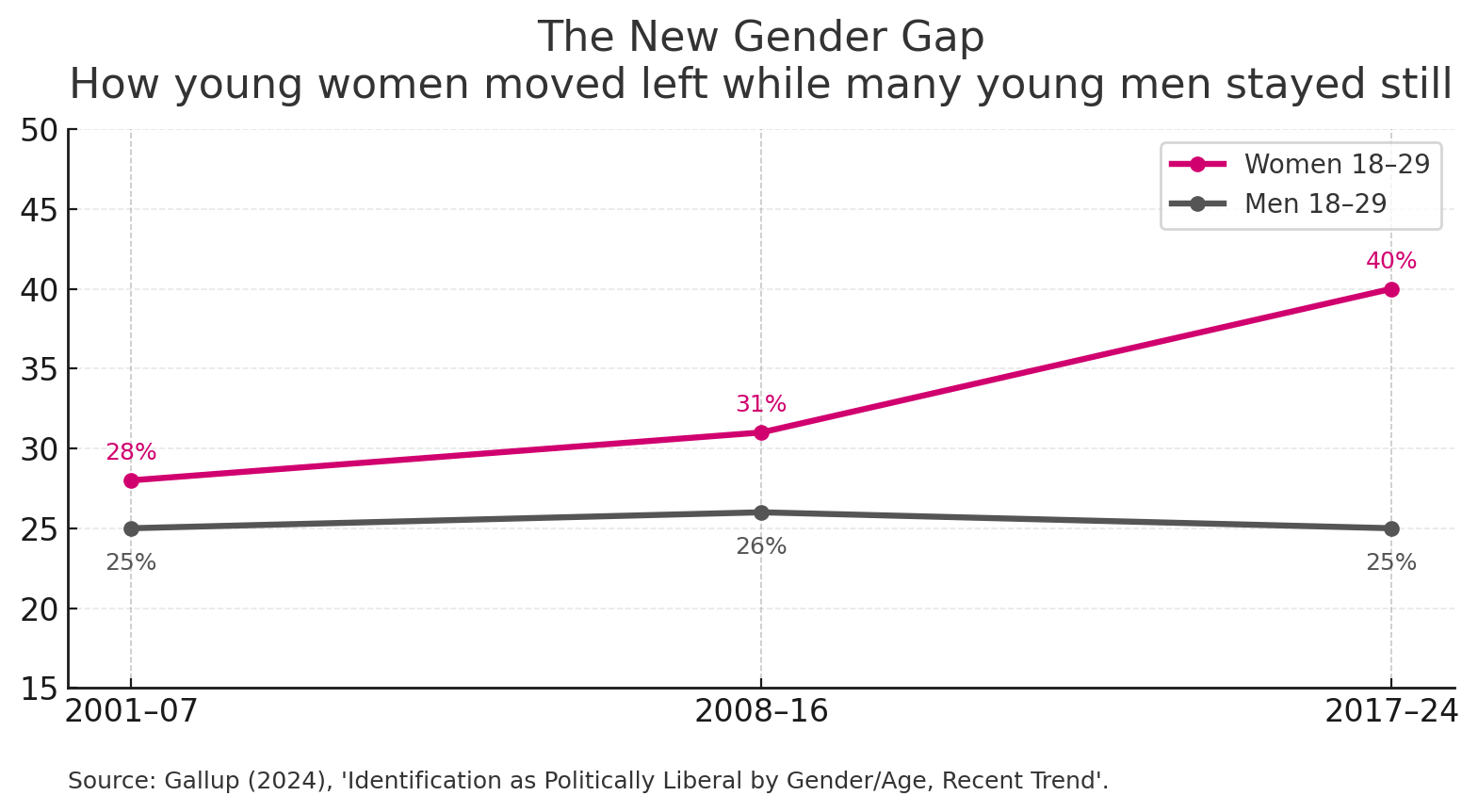

Behind these two lives sits a simple set of numbers.

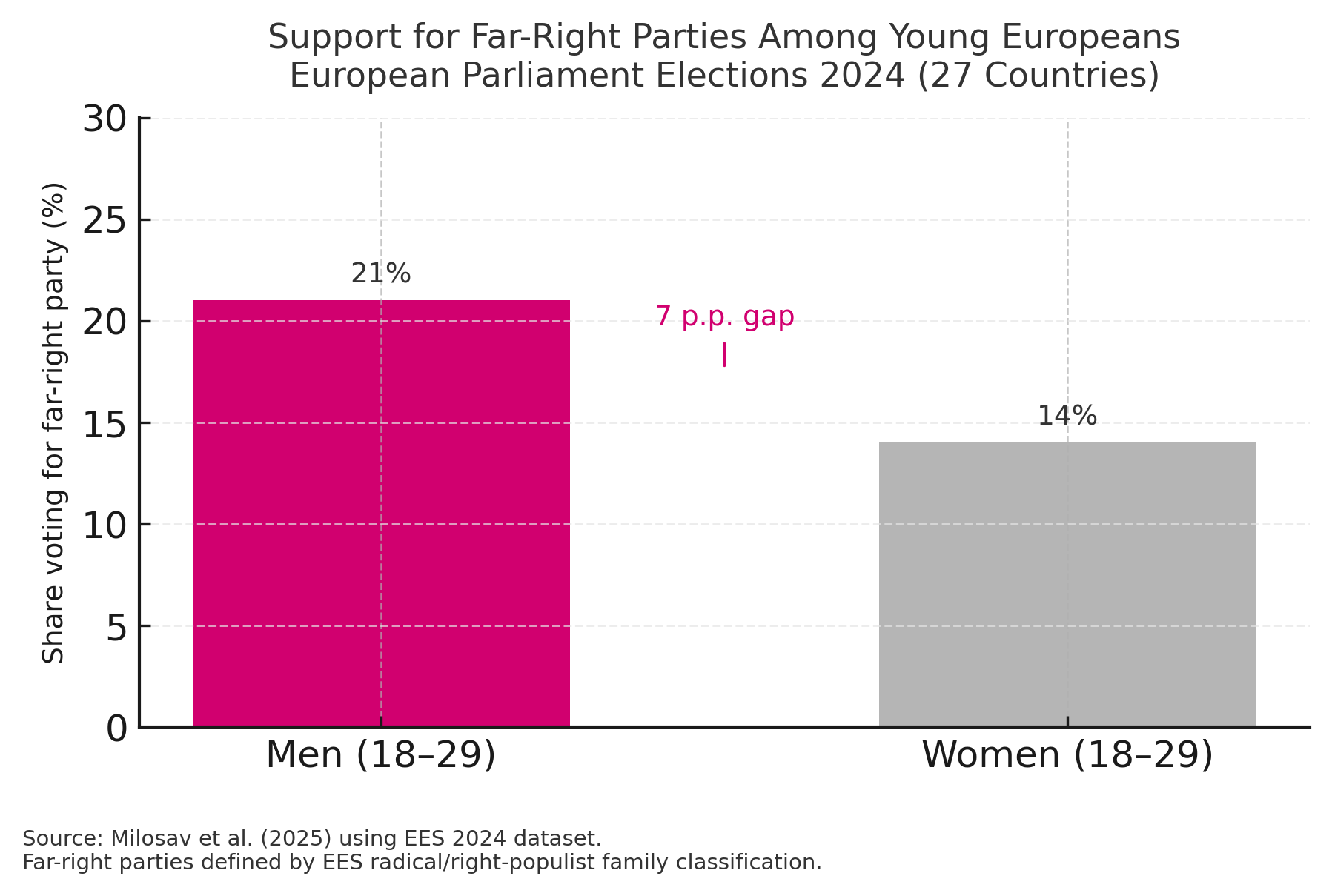

In most Western democracies, women in their teens and 20s have become decisively more liberal, more feminist, and more supportive of equality than men their age. Young men, by contrast, have changed far less – and in some countries have become more skeptical of feminism, more sympathetic to “anti-woke” rhetoric, more attracted to strongmen who promise order.

At the same time, Nate’s private problem is not just in his head. Across the rich world, young men are:

- more likely to be single than young women,

- more likely to report no sexual activity in the last year,

- more likely to say they want a partner but can’t find one.

Leah is inundated with options she doesn’t trust.

Nate is starved of options he desperately wants.

And both of them live inside platforms that monetize their attention and their emotions.

The Market Nobody Designed

Economists like to talk about two-sided platforms: places like Uber or Airbnb that connect two groups and profit from the match. Dating apps are the most intimate version of this.

They have created what we might call a digital sexual market – liquid, global, always on.

In this market:

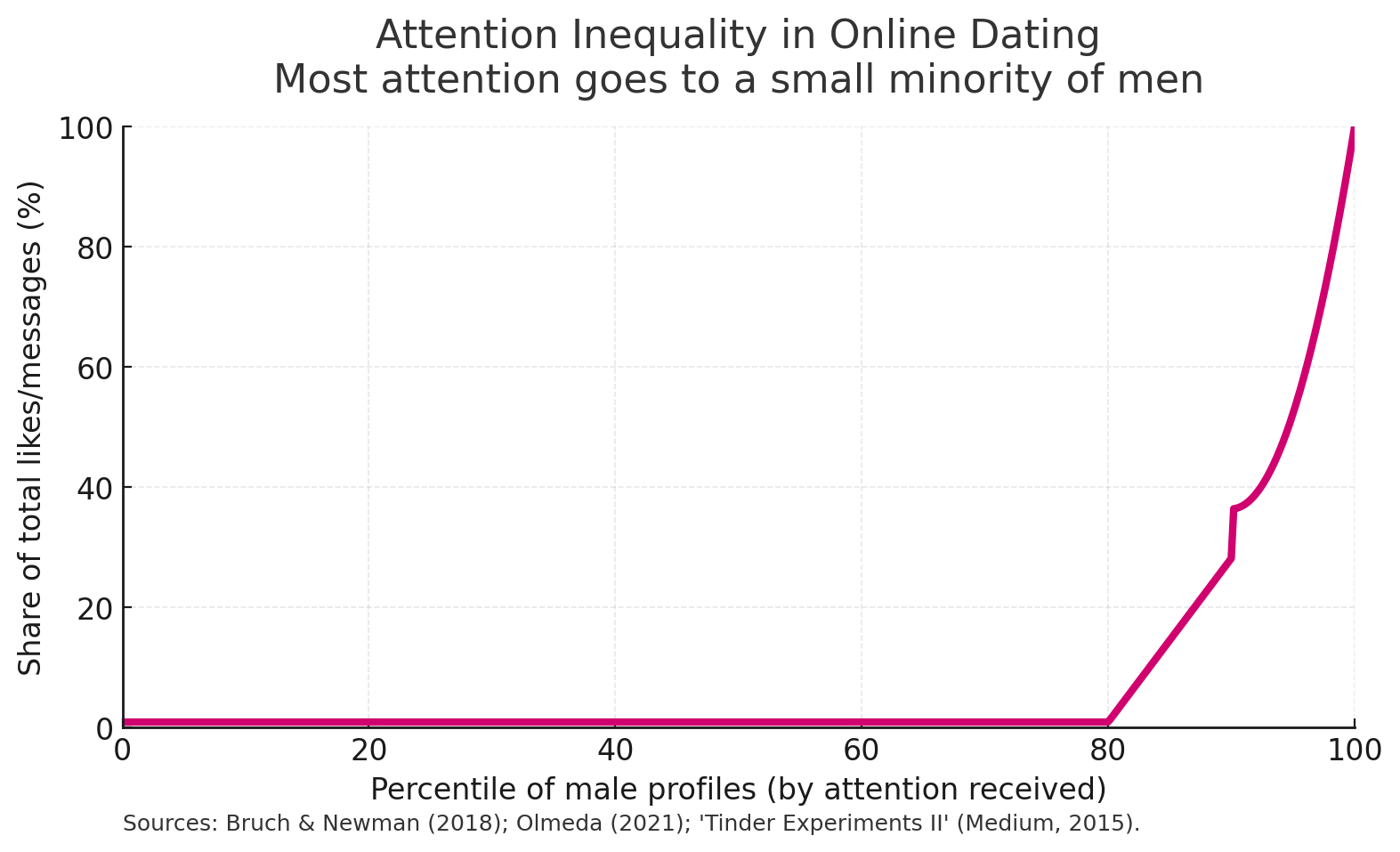

- There are more men than women. App user bases skew male. For heterosexual men like Nate, that means more competition.

- The distribution of attention is extreme. A small fraction of profiles – the most conventionally attractive or charismatic – get a huge share of likes and messages. The “middle” gets little or nothing.

- Women swipe more selectively; men swipe more widely. A typical male user will swipe right on most women he finds mildly attractive. A typical female user will swipe right on a small subset of men. For someone in Nate’s position – average looks, few photos, not very socially skilled – the probability of a match collapses.

If we drew this market, the Gini coefficient – the measure economists use for inequality – wouldn’t show income. It would show replies, matches, and dates.

- Bruch & Newman (2018): https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6082652/

- Olmeda (2021): https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.14076

- Tinder Experiments II (2015): https://medium.com/@worstonlinedater/tinder-experiments-ii-guys-unless-you-are-really-hot-you-are-probably-better-off-not-wasting-your-2ddf370a6e9a

For Leah, this market feels chaotic and noisy. She’s overwhelmed, skeptical that any of these men are serious, wary of harassment.

For Nate, it feels like a silent auction he keeps losing. The app interface is gamified: heart icons, streaks, suggestions to “boost” his profile for a fee. It promises possibility. The reality is often a long sequence of micro-rejections – likes that never turn into matches, matches that never respond, conversations that die after “hey”.

Over weeks and months, that has an emotional cost.

The behavioral economists of an earlier age – the ones who wrote about “animal spirits” in markets – were talking about investors whose moods swing between fear and greed. But there is another kind of animal spirit at work here: the way a person’s sense of worth rises or falls with the pings of a phone.

Nate starts to internalize a simple story:

“If no one ever matches with me, maybe I am worth nothing.”

That’s not a rational inference. It’s an emotional one. And emotional inferences are precisely what populist storytellers know how to harvest.

The Search for Blame

At first, Nate blames himself.

He tells himself he is too short, too awkward, too poor. He notices which of his friends have girlfriends and what they have that he doesn’t – a jawline, a car, a social circle that actually goes places.

Then something in his feed shifts.

A video suggests that “modern dating is broken.” Another claims that women today are programmed by Instagram to chase only rich men. A man in a podcast clip says that feminism has made women entitled and men disposable.

One night, Nate clicks. He listens. The words feel like relief.

These voices offer him three gifts:

- An explanation: It’s not your fault; it’s the system.

- An enemy: the system has a name – feminism, hypergamy, SJWs, the woke.

- An identity: you are not a loser; you are one of the “real men” who see the truth.

Some of these voices are slick self-help gurus. Some are angry YouTube ranters. Some are anonymous posters in forums like the one Nate now visits every night.

They differ in aesthetics but share a core script:

“The reason you are struggling is that women changed, and society took their side. You are owed respect and sex. You were robbed.”

The social psychologist Michael Kimmel calls this “aggrieved entitlement”: the feeling of having been promised something – status, sex, dominance – and then being cheated out of it. It is not simple victimhood; it is a rageful victimhood that says: “This was supposed to be mine.”

For Nate, this narrative is intoxicating because it turns humiliation into righteousness.

His animal spirits change sign. The despair is still there, but now it has a direction: against.

- What is the manosphere? UN Women explainer: https://www.unwomen.org/en/articles/explainer/what-is-the-manosphere-and-why-should-we-care UN Women

- Study: “From Privilege to Threat…” (2025) – psychological pathways: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12011899/ PMC

The story in Nate’s head is no longer “I am unlovable.” It’s “I have been wronged.”

And that change matters.

Because once you believe you have been wronged, the next natural question is: by whom, and what should be done about it?

The Bridge from Gender to Politics

For Leah, politics flows naturally from her daily life. When she walks home at night with keys between her fingers, she thinks about safety and policing. When she sees debates about abortion, she feels them in her body. When she sees another story about wage gaps or harassment at work, it fits into a pattern she already believes in.

For Nate, politics used to be background noise. Then the voices that explained his dating life started talking about politics, too.

They tell him that:

- Feminism is not just about women; it’s a power project by a liberal elite.

- The same people who “lied” about gender are “lying” about race, migration, climate.

- Politicians who stand up to “woke feminists” are the only ones willing to defend men like him.

He learns that there are parties and leaders who talk about restoring “real masculinity,” defending “traditional families,” pushing back against “gender ideology.” In their speeches, he hears echoes of the podcasts he now listens to daily.

At first it’s casual: he laughs at a meme mocking a female politician as hysterical. He shares a video of a commentator saying “men built this world and are treated like garbage.”

But slowly, voting and ideology stop being abstract policy choices and become something closer to a loyalty test in a gender war.

- Milosav et al. (2025) — The Youth Gender Gap in Support for the Far Right

https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/127750/1/The_youth_gender_gap_in_support_for_the_far_right.pdf

When survey researchers ask about hostile sexism – statements like “women seek to control men” or “when women lose, they cry discrimination” – the men who agree most strongly are also the ones most likely to support reactionary candidates, authoritarian governing styles, even political violence. The pipeline is not perfect, but the correlation is robust.

In Nate’s mind, the terrain one day looks like this:

- On one side: the apps, the HR trainings, the campus activists, the female journalist who blocked him on Twitter, the girl who unmatched him after he made a joke, the politician who says “believe women,” the HR memo about inclusive language.

- On the other: the podcaster who says he understands how men feel, the politician who jokes about “soy boys,” the YouTuber who swears women secretly want strong men to take control, the meme page that mocks “lib feminists.”

One side looks like the people who reject him.

The other side looks like the people who finally see him.

At some point, without consciously deciding it, Nate’s grievance crosses a border:

It stops being a personal grievance about dating and becomes a political grievance about the kind of society he lives in.

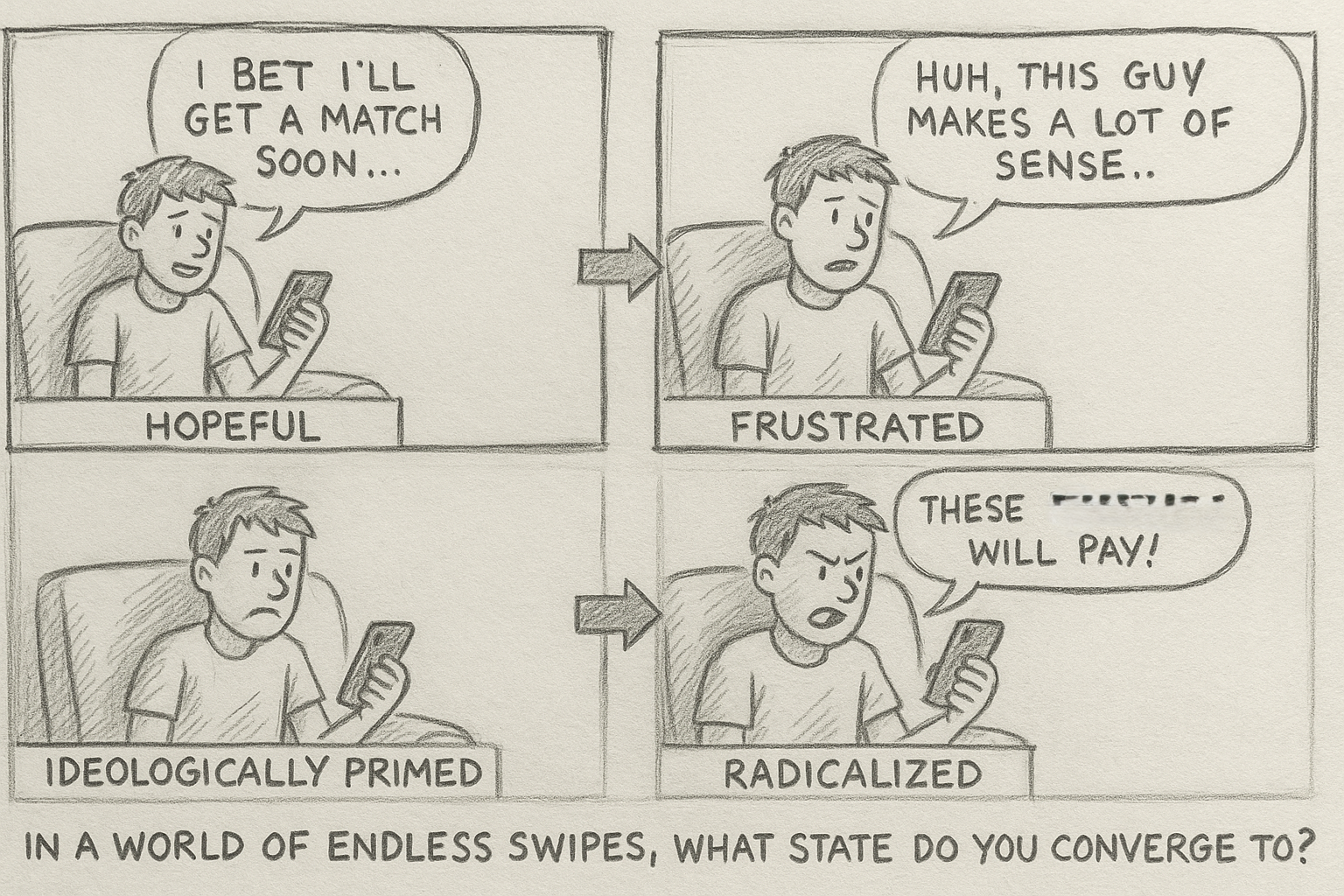

The Role of the Feed

None of this happens in a vacuum.

If you sit with Nate and watch his phone for an hour, you can see how the feed does the work.

He clicks on a video about “why men are falling behind in school.” The next recommendations include:

- “Why feminism is a scam”

- “Dating is impossible for average guys now”

- “How the left is destroying masculinity”

He clicks on one of those. The next batch leans harder:

- “The truth about female nature they don’t want you to know”

- “Why real men should oppose the woke agenda”

He follows a creator. That creator appears on a podcast hosted by a pundit who spends half his episodes on immigration, crime, and “globalist elites.” Nate’s feed starts showing those clips, too.

Before long, a session that started with “how to text women” ends with “why you should vote for leaders who will crush the woke mob.”

The technology doesn’t hate women or love authoritarians, but it does love engagement.

Anger is engaging.

Outrage is engaging.

The thrill of being told you are part of a small group who “see through the lies” is engaging.

So the algorithm serves more of it.

The economists’ animal spirits are now fully inside the machine. Our emotional volatility – our shame, pride, anger – have become a revenue stream. And they do not stay confined to the dating market or the comment section. They spill over into ballot boxes, protests, and in a few awful cases, into acts of violence.

When the Story Turns Dark

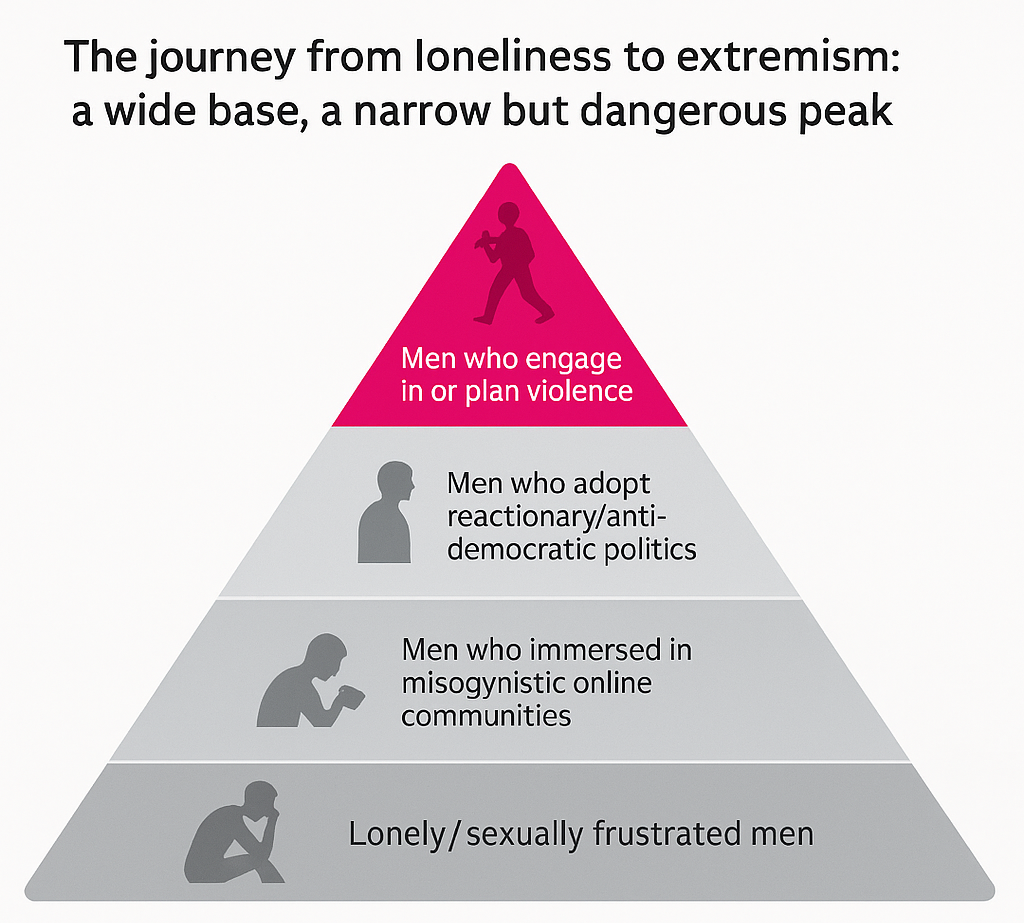

Most Nates will never hurt anyone.

Many will simply stay stuck in bitterness, or age out of it when they finally find a partner or a different narrative.

But if we zoom in on the men who did something terrible – the ones whose names make it into threat assessments and front pages – we see a familiar structure.

- A man who writes for pages about his inability to get a girlfriend.

- Years of rejection and social discomfort.

- Hours steeped in online forums glorifying those who “strike back” at women.

- A manifesto that reads like the ugliest threads Nate has started to scroll.

- A final act framed as “punishment” or “revolution.”

What is striking, reading these documents, isn’t how alien they are. It’s how familiar the first chapters sound.

They start where Nate is.

The goal of telling Nate’s story is not to excuse or to dramatize. It’s to see the pipeline early, when it is still made of fragile narrative threads rather than hardened ideology.

Because the story lines that carry him forward are all, at their core, stories about who owes what to whom.

Who owes whom respect, sex, a job, a future, a country that feels like home.

Those are economic questions as much as cultural ones.

We can chart the animal spirits of a generation of young men with three simpler graphs:

- The share of young men who are single and sexually inactive compared to young women.

- The gender gap in self-reported political ideology over time.

- The growth of search interest and engagement around manosphere terms and influencers.

We can make those charts. They will show lines moving in the wrong directions.

But what they will not show is the last scene, the one we do not want: another young man, alone in his room, writing a manifesto in which dating and politics, sex and power, women and “the system” all blur into one overwhelming story of grievance.

The Years When Stories Harden

By twenty-six, Nate is not quite the same boy.

He has moved twice, changed jobs three times, gained ten kilos. The warehouse became a call center became a delivery route. His friendship circle shrank as people coupled off and moved away. Leah, for her part, moved into a shared apartment with two friends and a cat, then to a different city for a nonprofit job. Their paths never crossed; they are statistical counterparts, not characters in each other’s lives.

The apps changed, too.

At first there were upgrades: smarter matching, better prompts, video dates during the pandemic. Then came the quiet attrition. Some of his friends met partners and deleted the apps. Women his age started writing “no hookups” and “looking for something serious” in their bios. Younger women seemed to swipe an entirely different cohort of men.

By twenty-six, Nate had a handful of short, halting relationships behind him, each ending in different words that all sounded like “you’re not enough.”

He still opens the apps sometimes. But he no longer thinks of them as possibility machines. He thinks of them as confirmation engines. They confirm what he has already decided to believe.

That belief is now thicker, more ideological. It is a story with chapters:

- The feminine delusion: feminism has given women unrealistic expectations.

- The male dispossession: men like him have been robbed by a rigged marketplace.

- The elite betrayal: universities, media, HR departments, politicians all took the other side.

The details are filled in nightly by the voices in his earbuds.

On slow afternoons, he listens to a three-hour podcast about “the crisis of masculinity.” On weekends he half-watches a livestream of someone explaining how “globalists” and “feminists” are two arms of the same octopus. The chat is full of jokes about soy, cucks, cat ladies, “NPCs”.

He laughs. He types a few comments.

The laughter doesn’t feel joyful. It feels like an exhale of pent-up contempt.

The regression lines would look neat and clean. The inner life would not.

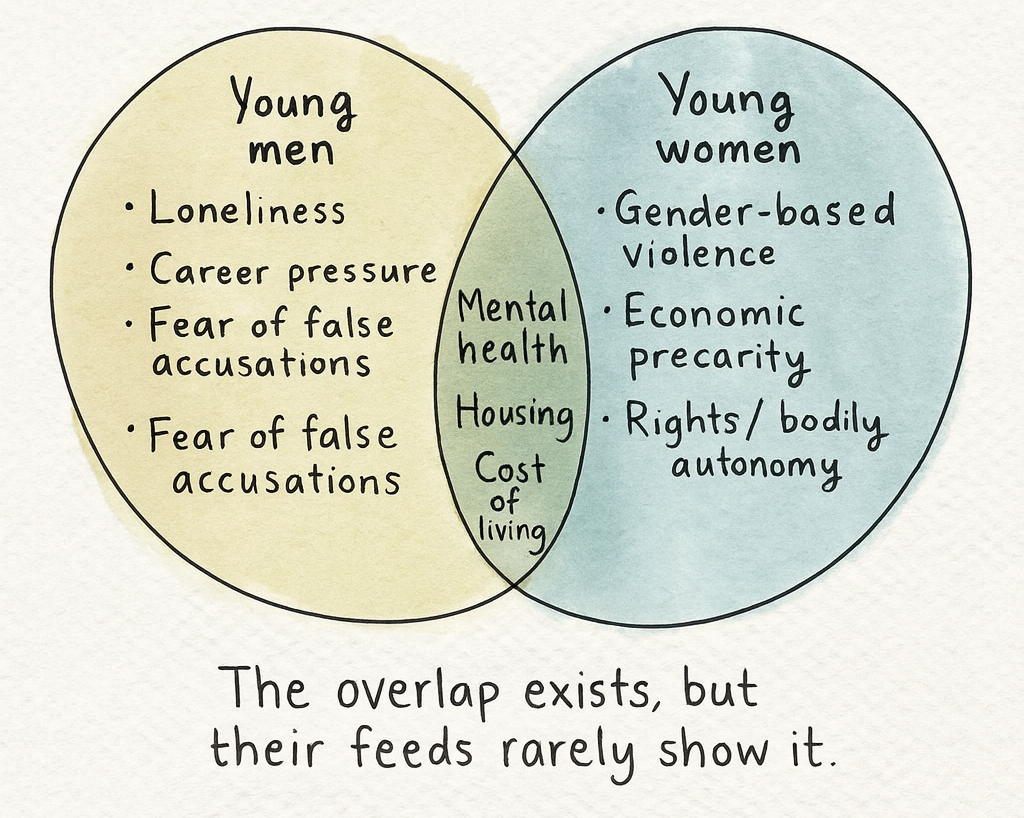

Leah’s Parallel Republic

Meanwhile, Leah has built a different life in her thirties.

Her group chats are full of wedding photos, IVF updates, fundraising links. Politics is that thing she folds into everything else: how much childcare costs, whether the bus runs late, whether her younger brother can afford rent.

On her phone, the “For You” page serves up therapists explaining trauma, creators breaking down labor law, historians deconstructing fascism, women talking to the camera about the feeling of having your body legislated.

Every once in a while, a clip of a smug man mocking feminism crosses her feed. She blocks, scrolls, rolls her eyes.

If you made a network map of her information world and Nate’s, you’d see two separate republics:

- One where the central nodes are feminists, journalists, academics, a handful of center-left politicians.

- One where the central nodes are manosphere influencers, anti-“woke” pundits, YouTube essayists railing against elites.

Sociologists sometimes talk about “affective polarization” – the idea that politics is no longer about disagreement over policies but mutual dislike, even disgust, between social camps.

For Leah, that affective line runs through issues like race, climate, abortion.

For Nate, it runs straight through gender.

To him, “their” side is the side that laughed at him, labeled him, ignored him, made jokes about men on TV, wrote think pieces about “the end of the man.”

To her, “his” side is the side that told women to be quiet, stay home, endure, and stop complaining.

They do not need to argue with each other for the split to grow. The architecture of their lives does the work.

Animal Spirits, Revisited

In the 1930s, when Keynes wrote about animal spirits, he was trying to explain why a purely rational model of the economy failed. People did not invest or consume based only on interest rates and expected returns. They were moved by confidence, fear, stories.

Imagine re-writing that chapter today, but instead of investors you focus on young men and women navigating sex, status, and politics in an online age.

You might write something like:

“Our decisions about love and loyalty are not made by a calculating machine. They are made by creatures whose self-respect rises and falls with a crush’s reply, whose tribal instincts are triggered by a meme, whose sense of injustice is sharpened by a viral story. These animal spirits, once confined to the bar or the barbershop, now ripple through networks of millions at light speed.”

Economists would naturally want to add structure.

They would point out that the supply and demand of attention are mismatched:

- The supply of potential partners is limited by geography, timing, and the constraints of time.

- The supply of images of potential partners is effectively infinite.

They’d observe that platforms financially benefit from keeping people slightly dissatisfied: hopeful enough to log back in, disappointed enough to pay for boosts.

They might model Nate’s experience as a repeated game with imperfect information, where each rejection updates his belief about his own “type” – gradually pushing that belief toward a pessimistic equilibrium.

They could simulate the effect of an algorithm that occasionally rewards him with a match – enough to prevent abandonment, not enough to change his overall status.

When a populist leader says, “They laugh at people like you,” Nate feels the sentence land in his body.

He remembers the unread messages, the campus feminist who rolled her eyes at a clumsy comment, the HR poster about “toxic masculinity.”

And he nods.

The Missed Conversation

There is a version of this world where Nate and Leah might have met in a very different context.

They might have sat in the same seminar on political economy, reading case studies about how economic dislocation and status loss feed support for demagogues. They might have heard a guest lecture about how male-dominated industries hollowed out by trade shocks or automation become breeding grounds for despair.

They might have had a structured conversation about how both of them experience vulnerability: Leah in fear and constraint; Nate in invisibility and drift.

And platforms are bad at nuance.

Their business model doesn’t reward the message: “You’re both hurting in different ways, let’s talk.”

It rewards messages like: “They are lying to you.” “They are laughing at you.” “They are coming for you.”

The effect, over time, is a quiet cognitive segregation.

Leah never sees how deeply some men are hurting until she stumbles on a thread after an attack and thinks, horrified, “How did it get this bad?”

Nate rarely sees the full texture of women’s fear and frustration; he sees curated clips that make feminist activists look hysterical or vindictive.

The missing overlap is where democratic politics is supposed to live.

Ending on a Threshold

One night, years from that first midnight scroll, Nate is on his couch. Another video autoplays, another rant about “the feminist regime.” His thumb hovers over the screen.

In one world, he scrolls past. He has found some other story to live inside: perhaps a community, a job, a relationship, a belief that channels his animal spirits into building rather than blaming.

In another world, he doesn’t scroll past. He clicks, he posts, he joins, he votes, he maybe someday fantasizes about, or even prepares for, something darker.

From the outside, the distance between those two worlds looks obvious.

From where he sits, it looks like the difference between one tap and another.

That is how thin the membrane can be between a private life and a public crisis.

The animal spirits of our time are not only in the bond markets.

They are also in the quiet rooms where young men sit with their phones, asking the oldest question in politics in the most personal way possible:

“Who am I in this world, and who took that from me?”