There’s more debt than money in the world

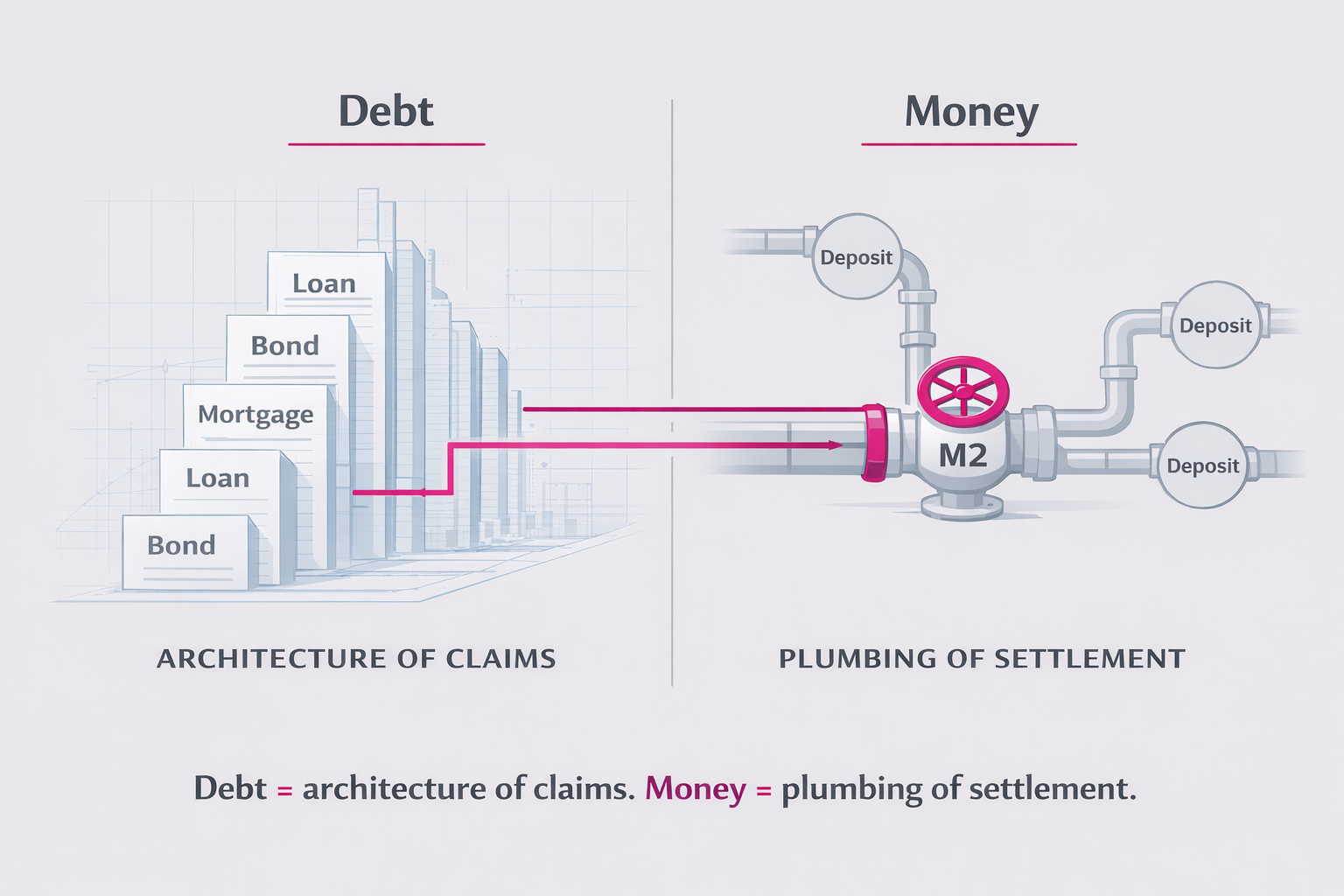

Debt is referenced as the stock of credit contracts (loans + bonds outstanding). Money (M2) is referenced as the stock of spendable settlement balances (currency + deposits) - “Global M2” here is a USD broad-money proxy, not “all money/wealth” or all financial assets.

The “gap” shows that the world runs on credit claims that are larger than the settlement layer, since contracts persist while balances circulate, and the stock of debt can exceed the stock of money.

So what?

So what if the world owes more than it can settle at any one moment?

So what if, in some broad sense, the global economy carries a larger pile of debt than the pile of “money” people imagine sitting behind it—like bills stacked in a vault, waiting to be counted and distributed to whoever shows up with an invoice.

If money were a finite stash, this would be scandalous. A civilization can’t owe more tokens than exist. Eventually the vault opens, the numbers are checked, and the entire planet discovers it has been living inside an accounting error.

But modern money is not a stash. It isn’t even, in the ordinary sense, a thing. It is a system for moving claims—quietly, constantly, and with such ordinary competence that it feels like nature rather than infrastructure. And debt is not a glitch in that system. It is one of the main ways the system drags the future into the present and asks everyone to behave as if that future is already partly real.

To understand why “more debt than money” is less paradox than description, you start where modern money is born. Not at a mint. Not at a printing press. At the moment someone is approved.

When a bank makes a loan, the popular story is that it hands out existing money: it takes what savers deposited and passes it along like a careful librarian. The actual story is stranger and more revealing. In the typical case, the bank creates a deposit when it creates the loan. A new balance appears in an account, spendable immediately; the bank records a new loan asset (you owe it) and a new deposit liability (it owes you, on demand). The Bank of England has described this plainly: in modern economies, most money is created by commercial banks making loans, and banks are not simply intermediaries lending out pre-existing deposits. (Bank of England)

Debt and money arrive together, like twins who will never quite get along. One is slow and moralized. The other is fast and taken for granted. The debt is the promise you will be living with for years. The deposit is the permission slip you can use today.

Then the deposit does what deposits do: it leaves.

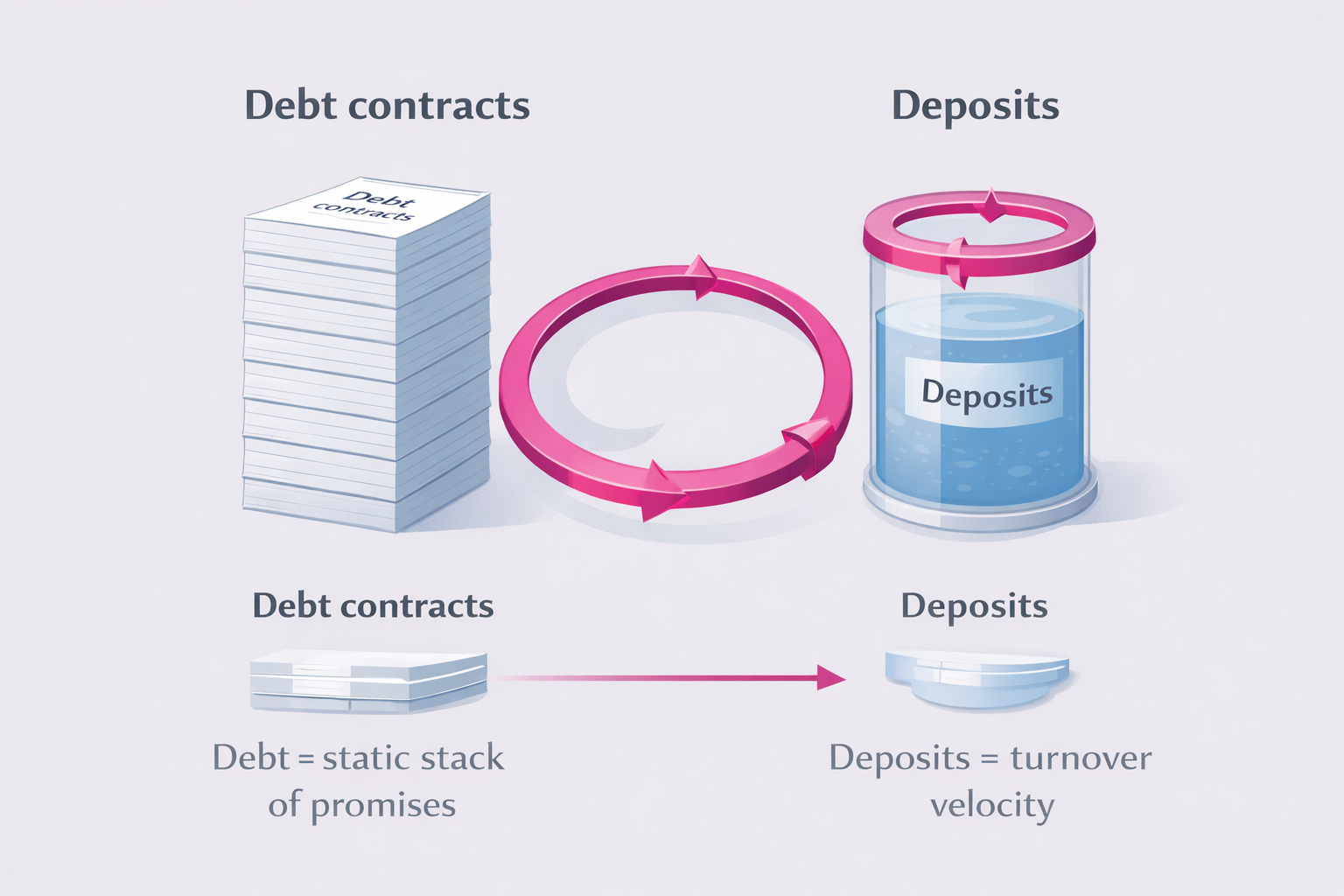

You pay someone. You buy something. The deposit moves into someone else’s account—maybe at another bank, maybe in another city—and the original debt stays put, still attached to you, still counting time. This is the first way the phrase becomes legible: money circulates; debt persists. The token moves; the promise remains.

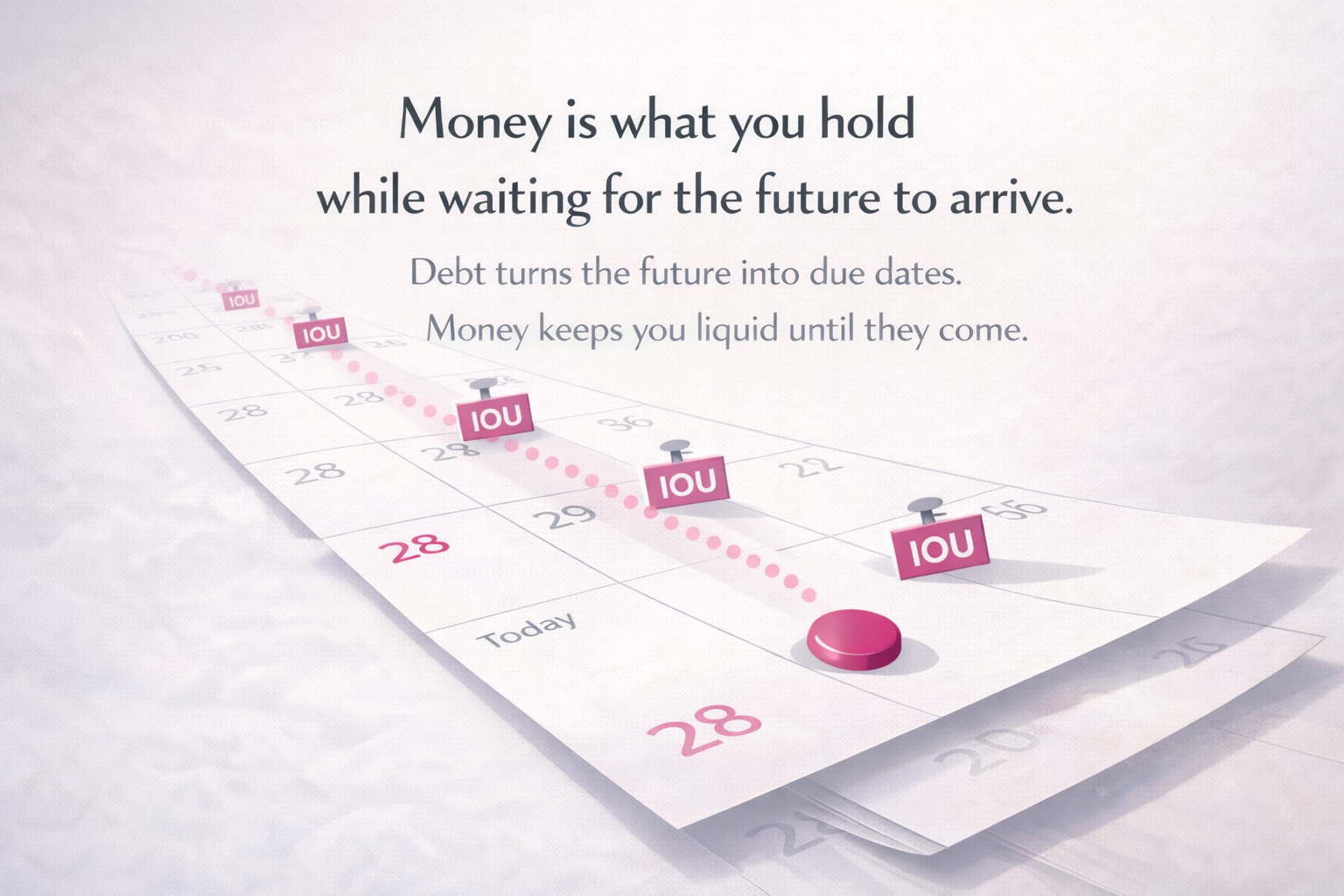

In a cleaner mental model, the idea of “time” in economics becomes relevant. Some economists treat money as a machine for converting uncertainty into a manageable calendar. Post-Keynesian economist Paul Davidson, building on Keynes, puts it in a form that’s unusually usable: money is what discharges contracts, and it is also a store of value—a vehicle for moving purchasing power through time, what he calls a “time machine.” (Paecon)

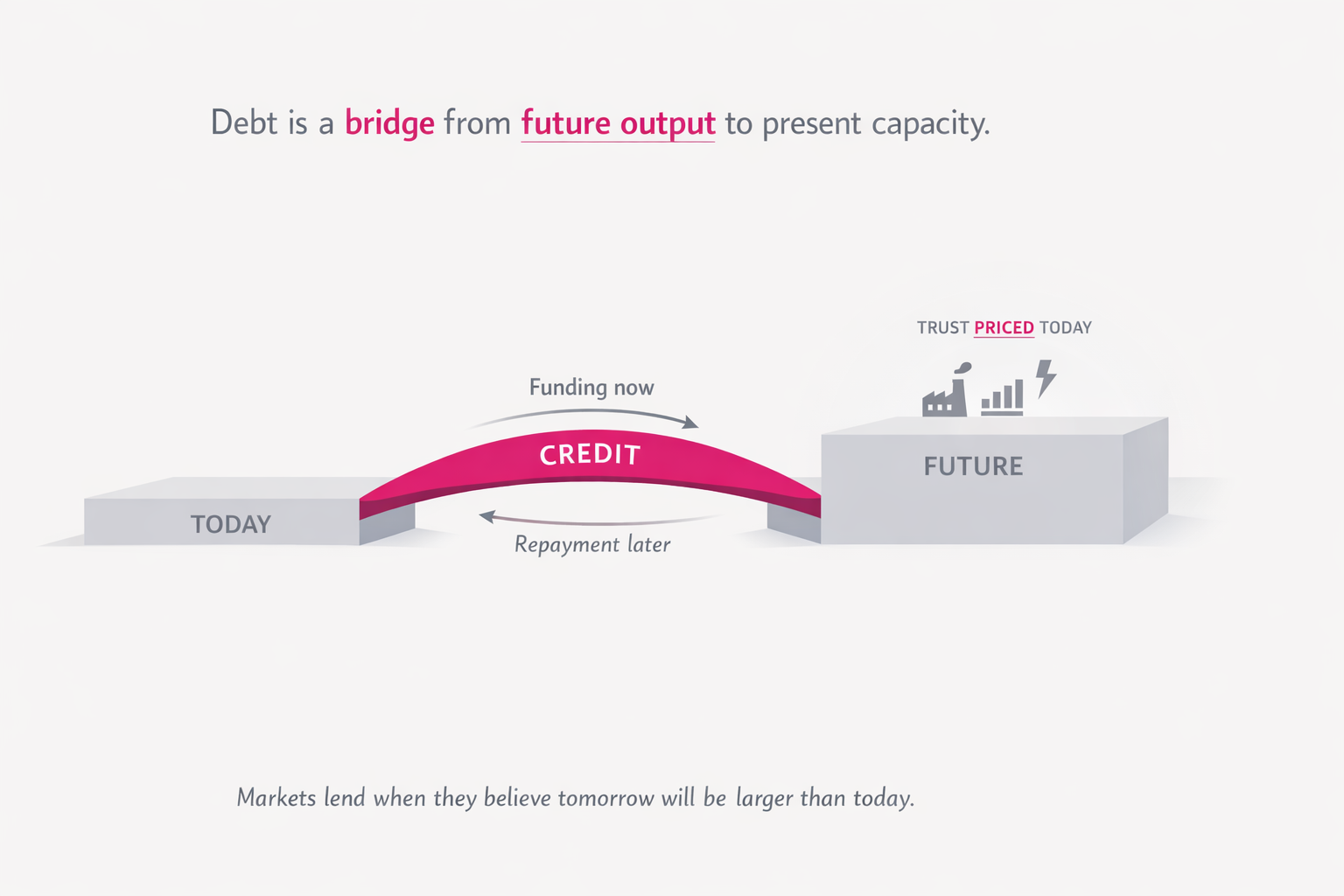

You don’t have to love the metaphor to see why it works. Most of life is a timing problem. Bills arrive on dates. Payroll is biweekly. Rent is monthly. Taxes have deadlines. The future is where your obligations live, and money is the instrument you rely on to meet them when they show up. Debt, meanwhile, is what happens when you pull a future payment into the present and promise to reverse the move later.

So a loan doesn’t just create a deposit. It creates a date.

It says: spend now, repay then. It pins an uncertain future to a schedule. And at every point in that schedule, what is being measured is trust—trust, above all, that the future will arrive with enough income attached to it to make the promise feel normal instead of ridiculous.

This is how the flow starts inside a country, and how it spreads without anyone holding a world meeting about it.

Households borrow. The newly created deposit becomes someone else’s income—because the first thing you do with spendable money is spend it. It becomes a seller’s balance, then a contractor’s balance, then workers’ balances, then a landlord’s balance, then the landlord’s mortgage payment. The same deposit can help settle a chain of obligations, sequentially, because money is reused as it moves. Debt is different: it stays behind as a long-lived claim on the future.

Companies borrow in the same way, but at the scale where “timing” has its own department. Firms borrow to buy inventory, to invest, to survive the lag between costs and revenue, to build capacity before demand arrives, to fund payroll before clients pay. The deposit created by a loan becomes wages in household accounts, payments to suppliers, leases, invoices. It disperses across the real economy like dye in water. The debt remains as a claim on the firm’s future profits.

The trust story sharpens here, because business borrowing is a priced belief about future demand. Credit is granted (or withdrawn) based on whether lenders think tomorrow will resemble the business plan. Optimism becomes measurable. So does doubt.

Then the government enters—not as a side character, but as the actor that quietly connects the whole system to a public calendar.

Governments spend into the economy and tax out of it. When the state pays salaries, benefits, procurement, recipients typically receive bank deposits. When the state taxes, it drains purchasing power from private deposits into government accounts. Government borrowing adds the public version of the promise: bonds, issued at scale, treated by markets as foundational when credibility is high and as suspicious when credibility fractures.

At this level, debt becomes a referendum on institutions. It’s no longer only “can a borrower repay?” It’s “does a state have the capacity to tax, the willingness to tax, the political stability to keep its promises intact, and the monetary credibility to keep the unit of account from slipping under stress?” That is what sovereign borrowing prices, whether or not anyone likes the moral implications.

And globally, the promise stack is enormous. The IMF’s Global Debt Monitor 2025 reports that global debt stabilized in 2024 at just above 235% of world GDP, edging up slightly to about $251 trillion in dollar terms. (imf.org)

This is the part where people often reach for a moral: too much debt, decadence, punishment. But since debt is also a measurement device, it measures how much future a society believes it can deliver. And because it is priced, it measures that belief in a way that doesn’t care about anyone’s self-image.

This is where the “low debt” becomes uncomfortable in a productive way.

Low debt can be restraint: a government (or a country) that could borrow easily but chooses not to. It can be ideology, caution, or a preference for self-financing through taxes and surpluses. But low debt can also be exclusion: a country that cannot borrow at humane terms because outsiders don’t trust its promises enough to accept them without demanding punishment in the price. The number alone can’t tell you which. The interest rate tells you. The currency tells you. The maturity profile tells you. The institutional story tells you.

Debt is not simply a burden. Sometimes it is a credit score.

To take the story beyond the national economy, we follow the same deposit logic across borders. Trade gets paid for through banking relationships and foreign-exchange conversion. Capital flows move through accounts. What crosses borders is usually not physical cash but claims—bank liabilities, institutional assets, settlement arrangements—re-expressed in different currencies.

Here trust stops being domestic and becomes geopolitical. Foreign-currency borrowing adds the harshest version of the calendar: repayment schedules exposed to exchange rates, external shocks, legal differences, political discontinuity. Global finance is threaded with cross-border bank lending and foreign-currency credit, which the BIS tracks through its international banking statistics and global liquidity indicators. (Bank for International Settlements)

In other words, the world’s money-and-debt system is not one closed loop. It is a hierarchy of promises, some treated as safe, some treated as provisional, some treated as speculative. The closer you are to the top—stronger institutions, deeper markets, credible monetary regime—the more easily your promises circulate. The farther you are from it, the more your future must be sold at a discount.

This is also why the “more debt than money” concept can be true without implying that repayment is mathematically impossible. It’s not a one-time matching problem. It’s a time problem.

Money is the circulating settlement token, reused again and again as payments move through the economy. Debt is the stock of promises written across years and decades: mortgages, corporate loans, government bonds, cross-border credit. Debt is slow. Money is fast. Debt accumulates because the future is continuously being pulled into the present, contract by contract.

Daniela Gabor gives a name to this: “monetary time.” She argues that treating time as mere uncertainty misses how states and private finance actively order time on balance sheets to produce credible promises to pay at par. (IDEAS/RePEc)

Debt is a technique for making tomorrow tradeable today. The system is constantly trying to manufacture credibility about the timeline—about whether the promise will hold its value, arrive when due, and remain accepted as settlement.

So what?

So the phrase matters because it tells you what kind of civilization this is. A credit-based civilization is one in which the present is partly funded by claims on the future, and the future is continuously being priced.

The real danger is not that the world has “more debt than money.” That comparison is used as a lens (not a diagnosis). Debt is the stock of promises, while money is the settlement layer those promises ultimately clear through.

The danger begins when the promise stack grows faster than the economy’s capacity to service and refinance it—when obligations compound, growth disappoints, and stabilization requires political choices a society can’t or won’t sustain. Or when the system becomes structurally dependent on rolling promises forward and, suddenly, the marginal buyer vanishes. In that moment, trust doesn’t fade; it cliffs. Rates jump. Math worsens. The future shrinks. What looked like confidence starts to look like denial.

But before the cliff—before the snap—debt is often simply the system doing what it was built to do: converting a belief about tomorrow into spending power today.

What did we borrow for?

Did the promises finance homes, infrastructure, productivity, resilience—things that make tomorrow larger than today?

Or did they finance a present that is being made expensive on purpose—asset inflation, consumption without investment, politics that treats the future as someone else’s inconvenience?

“More debt than money” is a reminder that our economy is a machine for turning forecasts into claims. The question is whether the future we’re borrowing against is one we’re actually building.

Sources

Bank of England (2014) — Money creation in the modern economy (HTML)

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/2014/q1/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy

Bank of England (2014) — Money creation in the modern economy (PDF)

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy

Paul Davidson (2019) — What is modern about MMT? A concise note (PDF)

https://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue89/Davidson89.pdf

IMF (2025) — Global Debt Monitor 2025 (PDF)

https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/GDD/2025%20Global%20Debt%20Monitor.pdf

IMF (2025) — Global Debt remains above 235% of world GDP (blog)

https://www.imf.org/en/blogs/articles/2025/09/17/global-debt-remains-above-235-of-world-gdp

BIS (2025) — International banking statistics and global liquidity indicators (Oct 30, 2025)

https://www.bis.org/statistics/rppb2510.htm

BIS (2025) — International banking statistics and global liquidity indicators (Jul 31, 2025)

https://www.bis.org/statistics/rppb2507.htm

Daniela Gabor (2023) — “(Shadow) money without a central bank…” (RePEc page)

https://ideas.repec.org/p/osf/socarx/ajx8f.html

Gabor & Vestergaard (2017) — Time and (shadow) money (PDF)

https://postkeynesian.net/media/events/Gabor_and_Vestergaard_2017.pdf