The Vibes Economy — Civic Literacy in an Age of Emotion

How America Under‑Teaches Money and Government — and Elects on Emotion

Prologue

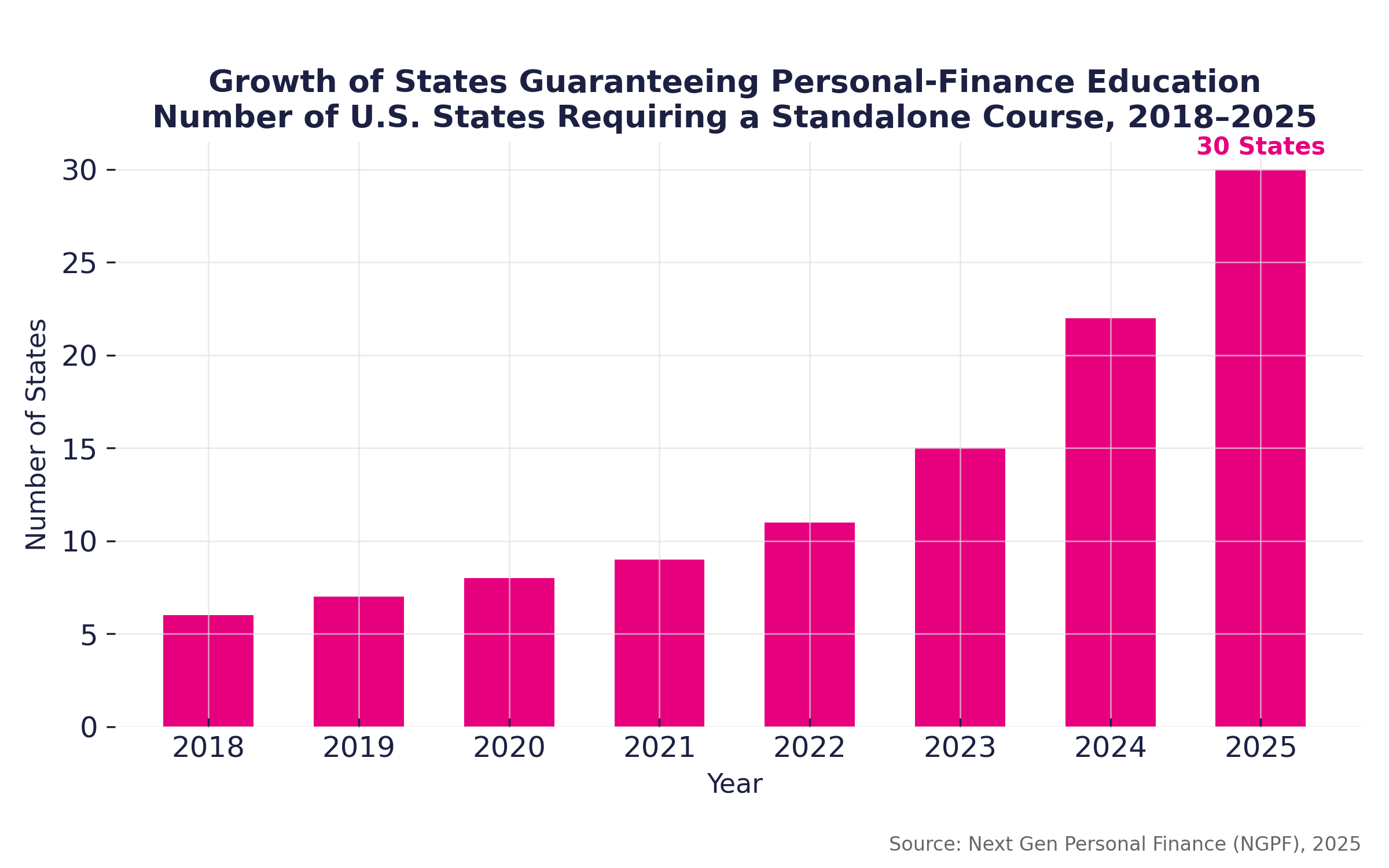

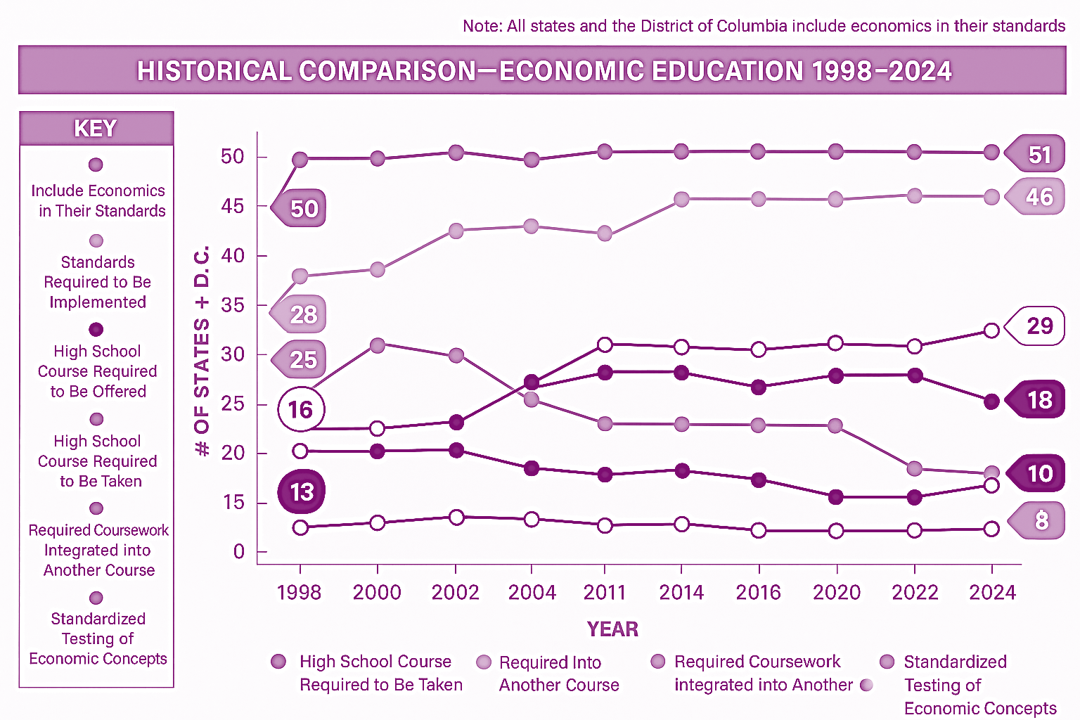

Across the United States, parents, lawmakers and students celebrate a rapid expansion of personal‑finance mandates in high schools. According to the Council for Economic Education’s 2024 Survey of the States, 35 states now require a standalone personal finance course and 28 require economics to graduate, increases of 12 and three states respectively since 2022 councilforeconed.org. However, the nonprofit Next Gen Personal Finance (NGPF) reports that as of November 2025, only 30 states actually guarantee that every student will complete such a course, with twenty still in phased implementation (ngpf.org).

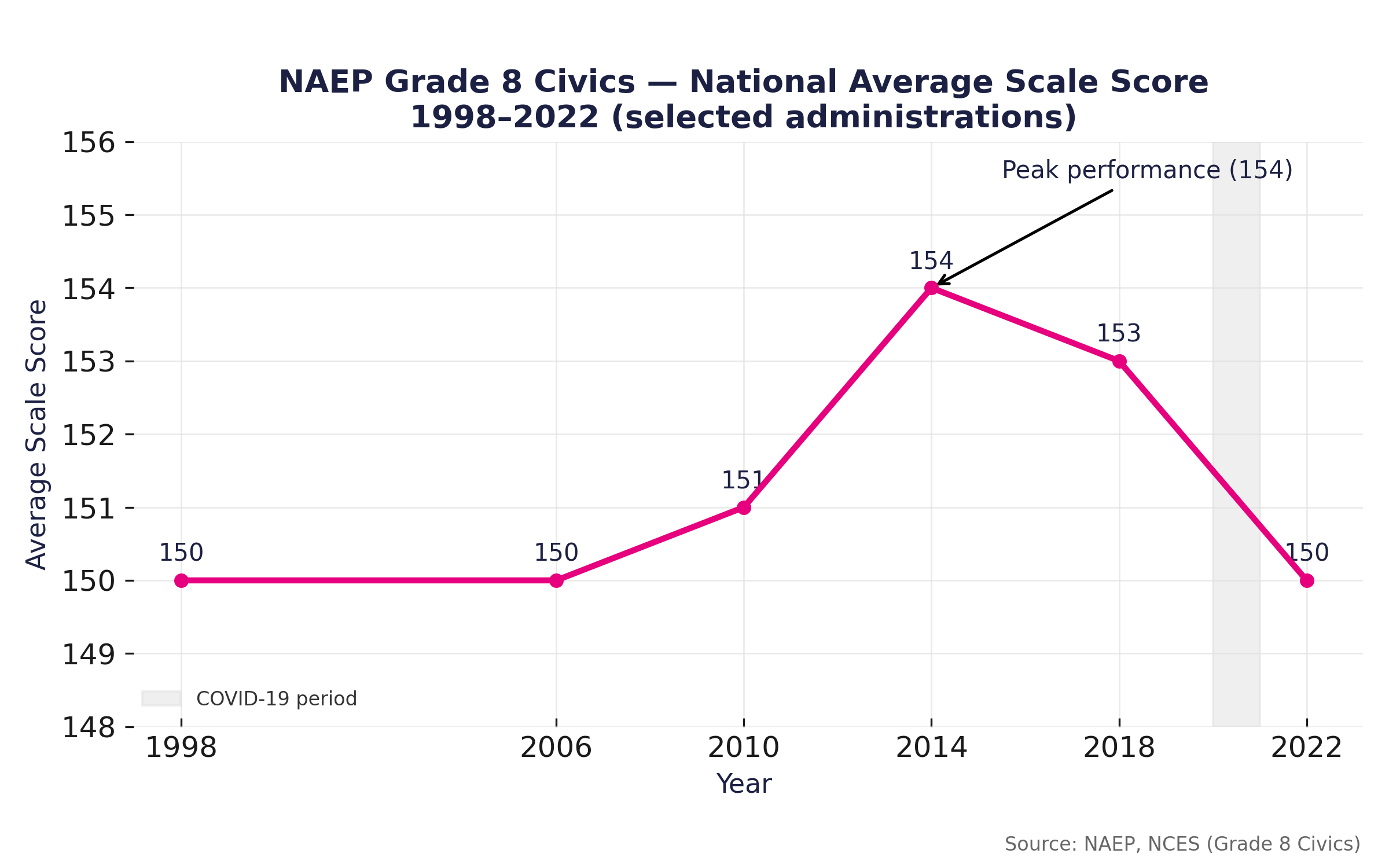

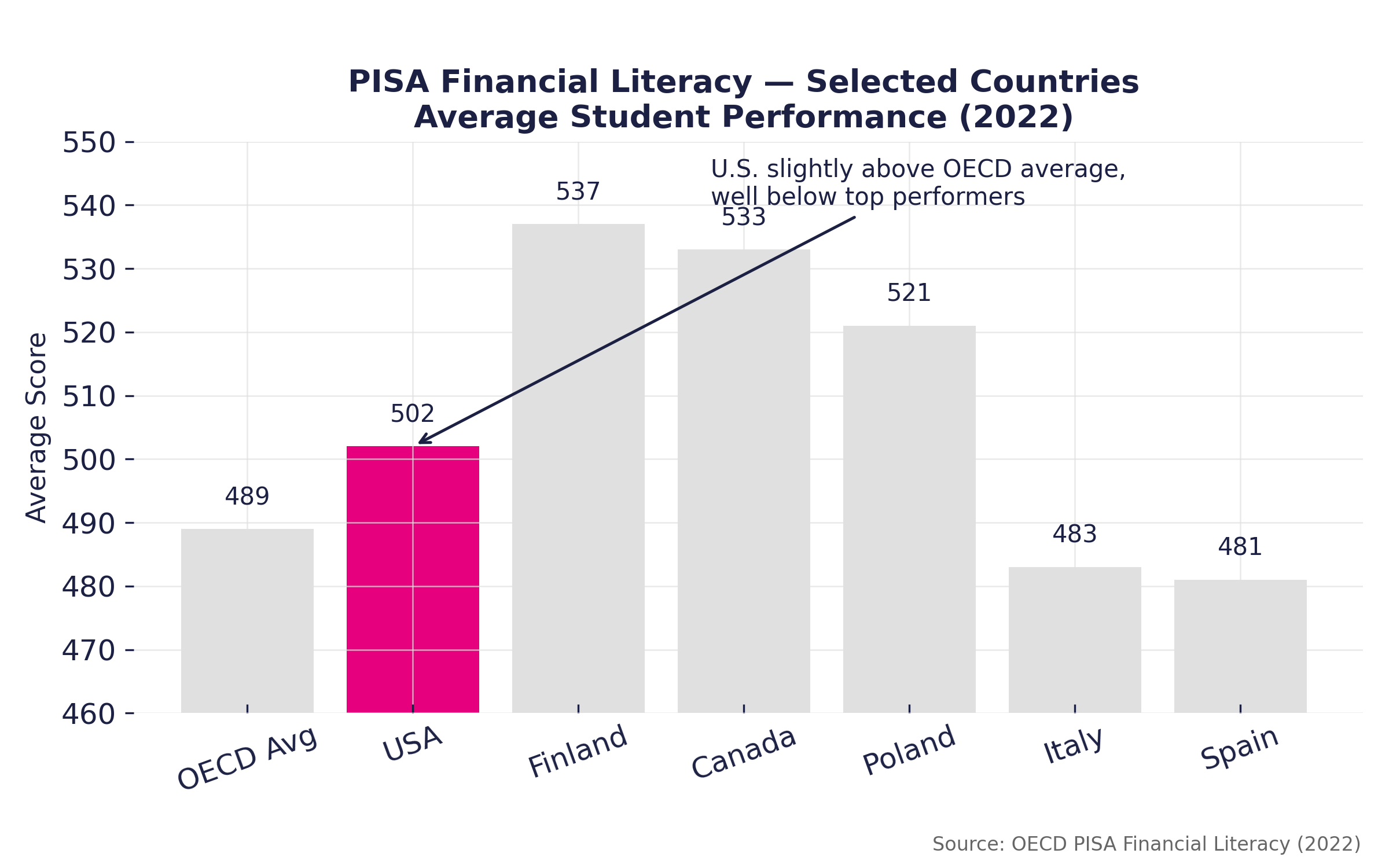

On paper this looks like an historic leap forward. Yet civic and economic literacy among voters is stagnant or declining. The NAEP civics assessment for eighth‑graders shows the national average score bouncing between 150 and 154 since 1998, returning to 150 in 2022, exactly where it stood in 1998 nces.ed.gov. On the global stage, the United States’ PISA financial literacy score of 505 is barely above the OECD average (498), and its performance is statistically indistinguishable from countries like Austria and Poland oecd.org.

America’s patchy financial‑education gains are not translating into economic citizenship. Despite new requirements, implementation remains uneven (20 of the 30 “guarantee” states are still phasing in their courses ngpf.org), and many states embed only a few personal‑finance lessons within other subjects. At the same time, civic education has withered: only four years since 1998 has NAEP measured eighth‑grade civics, and scores show no progress nces.ed.gov. The Atlantic calls it “a lost decade in American education.” Reading and math scores have fallen to levels unseen in a generation, with a third of middle-schoolers unable to summarize a basic text. The Atlantic, “America Is Sliding Toward Illiteracy,” October 14 2025

But beyond the classroom, this educational decline is reshaping the electorate itself. When citizens can no longer read budgets, laws, or even the fine print of their own credit, democracy begins to operate by intuition rather than understanding — by vibe, not by reason.

Admittedly, the sentiment itself—the cry for fairer living conditions—is not misplaced. As we have written in Economic Inequality, Social Mobility, and Political Polarization in the U.S., 1924–2024, the grievances driving such demands are real and long-accumulated. The problem lies not in the goals but in the means promised to achieve them, which often ignore the fiscal and legal scaffolding required to make change durable.

The result is a civic marketplace where emotion fills the vacuum left by understanding. As argued in From Citizen to Idiot, education is not merely instruction but initiation; a process through which individuals become capable of collective judgment. Absent that, participation becomes reaction, and citizenship dissolves into sentiment.

NGPF’s Live U.S. Dashboard tracks states guaranteeing that every high‑school student completes a one‑semester personal‑finance course. As of 4 November 2025 there are 30 guarantee states: Alabama, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia and Wisconsin ngpf.org. Ten states have fully implemented the requirement and 20 are still in progress ngpf.org. Other states have piecemeal standards; for example, Iowa reports 96.5 % implementation, whereas New York requires only 4 % of students to take a personal‑finance course ngpf.org ngpf.org.

Growth Over Time

Momentum has surged in recent years. The number of guarantee states climbed from 11 in 2021 to 17 in 2022, 25 in 2023, 26 in 2024 and 30 in 2025, reflecting an unprecedented pace of adoption ngpf.org. However, NGPF’s data reveal that implementation lags legislative headlines. Many states set future graduation cohorts (often classes of 2027 or 2028) as the first group subject to the requirementngpf.orgngpf.org. Without consistent enforcement, requirements risk being hollow mandates.

NAEP Civics

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is the only nationally representative measure of U.S. civic knowledge. For eighth‑graders, average civics scores have flat‑lined: 150 points in 1998, 150 in 2006, 151 in 2010, 154 in 2014, 153 in 2018 and back to 150 in 2022 nces.ed.gov. The 2022 decline erased modest gains made in 2014 and 2018. Fewer than one‑quarter of students reach the “Proficient” level, and disparities by income and race persist. In short, civics education is neither improving nor keeping pace with societal complexity.

PISA Financial Literacy

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests 15‑year‑olds’ ability to apply financial knowledge. In 2022 the United States scored 505 with a 95 % confidence interval of 496 – 515, statistically indistinguishable from Czechia (507), Austria (506) and Poland (506) oecd.org. The OECD average across 14 participating economies was 498 oecd.org. Countries like Norway (489), Brazil (416), Saudi Arabia (412) and Malaysia (406) trailed far behindoecd.org, while only the Flemish Community of Belgium (527) and Denmark (521) significantly outperformed the U.S. The OECD report notes that Spain and the United States improved compared to 2015, whereas Poland improved compared to 2015 but declined relative to 2018oecd.org.

Mandates Without Mechanisms

The gap between personal and public literacy is visible in curriculum data.

According to the Council for Economic Education, nearly every U.S. state now includes economics in its standards — but the number that actually require a high-school economics course has barely changed since the late 1990s, and those that test the subject have fallen by more than half. By contrast, personal-finance continue to expand, reflecting an emphasis on individual solvency over systemic understanding.

The result is a generation encouraged to balance household budgets but not public ones.

Iowa vs. New York

The gulf between policy and reality is stark. Iowa has mandated a one‑semester personal‑finance course since the class of 2023 and has reached 96.5 % implementation ngpf.org. By contrast, New York—home to Wall Street—still embeds financial education within social‑studies and career‑technical frameworks, requiring only 4 % of students to take a semester‑long course ngpf.org. Without statewide enforcement and teacher training, low‑income districts are most likely to miss out.

Uneven Economics Requirements

CEE’s survey shows that 28 states require economics for graduation councilforeconed.org. But many of the recent increases come from administrative changes that add economic concepts to civics or social‑studies courses councilforeconed.org rather than full‑year classes. Some states even considered eliminating economics to focus solely on personal finance, an idea CEE warns against councilforeconed.org. North Carolina and Virginia present a more promising model: students must complete one year of economics and personal finance, placing the subjects on equal footing councilforeconed.org.

The Politics of Vibes

Low civic‑economic literacy feeds a politics driven by emotion rather than feasibility. Local campaigns increasingly center on universal promises — free transit, blanket rent relief, debt forgiveness — offered without reference to legal or fiscal limits.

Yet municipal finance operates under strict balanced-budget laws, tax earmarks, and bond obligations. Farebox revenue, pension liabilities, and capital budgets are interdependent systems that cannot simply be wished away. Implementing even one of these proposals in a city like New York would require a full legislative chain under state law:

- 📝 Bill drafting: a state legislator introduces a bill authorizing the city to modify its tax structure or create new revenue sources.

- 🏛️ Committee review: the proposal passes through fiscal committees such as Ways and Means and Finance for analysis of budgetary and distributional impacts.

- 🗳️ Floor votes: both chambers debate and vote; amendments often reshape the revenue mechanics.

- 🔁 Reconciliation: any differences between the versions are resolved in conference before final passage.

- 🖋️ Executive approval: the governor can sign or veto the bill; only after approval does the measure empower the city.

- 🧮 Implementation: local agencies then adjust tax codes, transit budgets, and housing programs within balanced-budget and bond-rating constraints.

For context, New York City Transit’s farebox operating ratio fell from 52.8% (2019) to 31.9% (May 2022) versus a 40% budgeted target, illustrating why “free transit” promises must identify replacement revenues under GAAP-balanced, four-year-plan rules. Office of the New York State Comptroller

Promises that skip these steps remain rhetorical. Without a population fluent in how laws and budgets move from aspiration to statute, sentiment outweighs solvency — and the rhythm of politics follows emotion, not arithmetic.

🇺🇸 vs 🇪🇺 Democratic Socialism and Social Democracy

The gap between how progressive-policy movements are framed in the United States and how social-democratic regimes function in Europe helps explain why so much policy debate becomes about vibes rather than structure.

In the U.S., the label Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) captures much of the contemporary “democratic-socialist” impulse. The organisation defines its vision as seeking “to replace” the capitalist system with “democratic socialism, a system where ordinary people have a real voice in our workplaces, neighbourhoods, and society.” (Democratic Socialists of America (DSA))

Rather than a detailed roadmap of taxation, budgets and public-enterprise governance, the emphasis is on power, ownership and equity—for example public ownership of key economic sectors such as energy or transportation. (Democratic Socialists of America (DSA))

In other words: the rhetorical pitch is justice-oriented; the fiscal mechanics are often under-specified or left for later development.

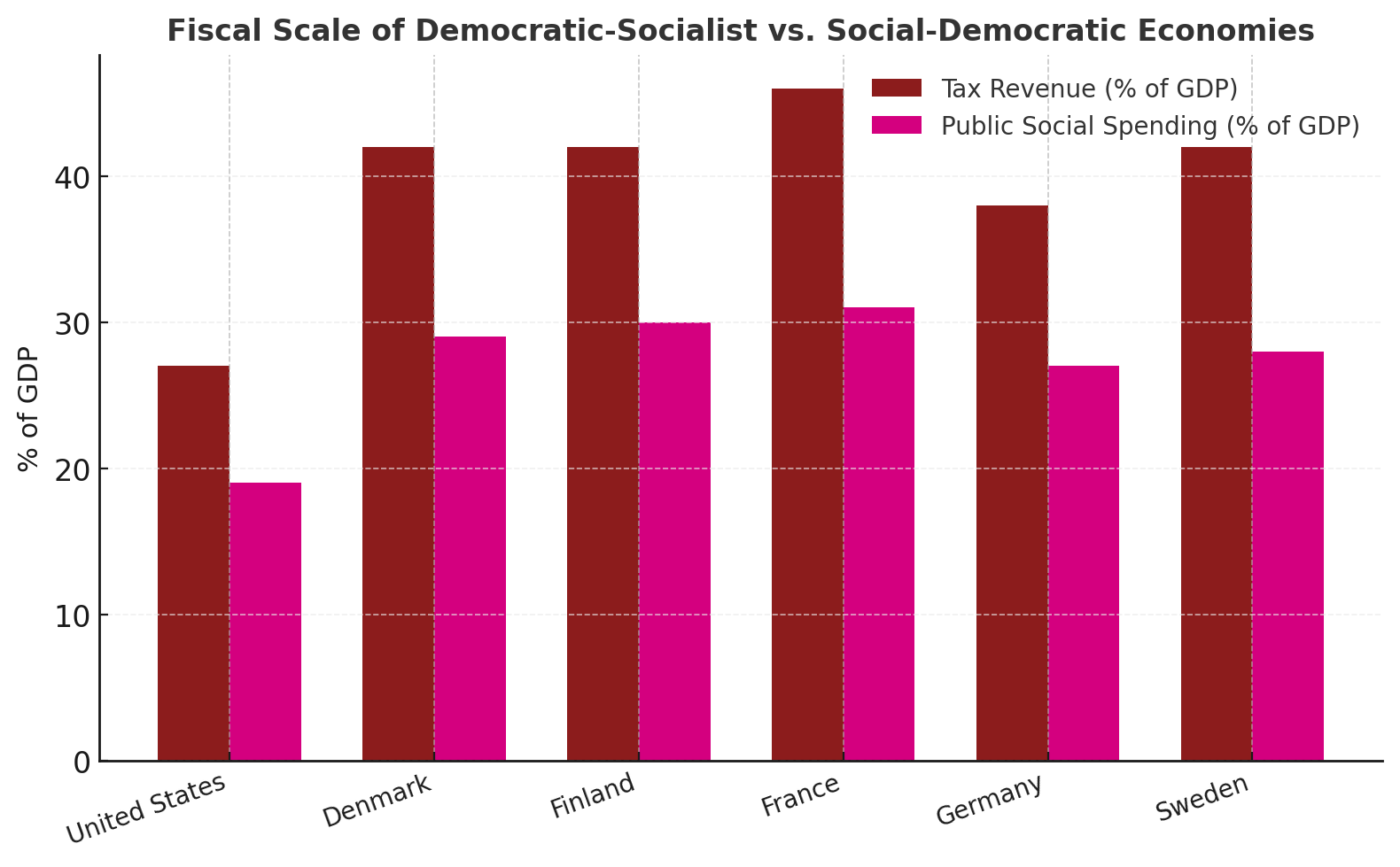

By contrast, European social-democratic traditions operate within the institutional framework of market capitalism supplemented by active redistributive states. Countries frequently cited as examples maintain public social-spending programmes amounting to over a quarter of GDP, financed by broad-based taxation, collective bargaining and automatic stabilisers. For example, the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) notes that in some member nations public social spending reaches “just over 30 % of GDP”. (OECD)

The OECD Social Expenditure Database (SOCX) provides internationally-comparable data to track such outcomes across 38 countries. (OECD)

Thus: social-democracy as governed practice emphasises mechanics of redistribution—tax, budget, service delivery—rather than primarily moral signalling.

In succinct contrast:

- The American democratic-socialist posture tends to emphasise universal rights, de-commodification, public power, but often leaves the revenue-and-budget mechanics in the background.

- European social-democratic regimes emphasise explicit redistribution, welfare-state budgeting, labour-market institutions, and operate within the constraints of fiscal-governance.

Without a citizenry fluent in those mechanics—tax bases, budget constraints, bond ratings, pension obligations—the two models can appear interchangeable to voters, and policy debate becomes one of moral resonance rather than institutional reality.

📈 Fiscal Scale of Democratic-Socialist vs. Social-Democratic Economies

The difference is actually measurable. European social-democratic states fund redistribution through broader tax bases and higher social outlays, while the United States operates at a much smaller fiscal scale.

In Denmark, Finland, France and Sweden, tax revenue consistently exceeds 40 % of GDP, and public social spending absorbs roughly 30 %. In contrast, the U.S. collects just ≈ 27 % of GDP in tax and spends ≈ 19 % on social programs — a gap of more than ten points on both axes.

This divergence illustrates the essence of the “justice vs. mechanics” contrast: European social democracy institutionalises equality through sustained fiscal design, while American democratic socialism often voices equality as moral principle but without equivalent budgetary architecture.

- Inadequate civic‑economic education leaves voters unaware of how municipal budgets work. Few states teach students about balanced‑budget laws, tax earmarks or bond covenants. Even where personal finance is mandated, it rarely includes public‑finance concepts.

- Patchy implementation means that in many districts the new requirements exist only on paper. Underfunded schools are less likely to add qualified teachers or separate courses, exacerbating inequity.

- Declining civics performance shows that students are not learning how government functions or how to evaluate political claims. Without basic civic knowledge, voters may treat campaign promises as wish lists rather than plans constrained by law.

- Emotion‑driven politics thrives in this vacuum. Candidates can promise free transit or rent cancellation without facing informed scrutiny. As a result, cities risk electing leaders with proposals that conflict with statutes such as the FEA and balanced‑budget requirements comptroller.nyc.gov.

Fixes and Forward Path

- Make economics and civics mandatory statewide. Mandate a stand‑alone semester of economics and a civics course focusing on federal, state and local budgeting. Tie high‑school graduation to mastery of these subjects.

- Require public‑finance modules within personal‑finance courses. Teach students about balanced budgets, bond ratings, transit finance and pension obligations. Draw on real local data (e.g., MTA farebox ratios osc.ny.gov) to show trade‑offs.

- Test and report outcomes. Incorporate civic‑economic literacy into state accountability systems and publicly report NAEP civics results to spur improvement.

- Guarantee equitable access. Prioritize implementation in low‑income districts and fund teacher training and curriculum development. Track progress by district, not just by state averages.

- Use simulations and capstones. Require students to balance a mock city budget under legal constraints, exposing them to the hard choices policymakers face.

Epilogue

A republic begins with education and ends with emotion. Between those poles lies everything we call democracy. The irony is that emotion fills the void where literacy should live. The anger, the hope, the cry for dignity — all of it is real and justified. But when noble intent travels without understanding, it becomes performance, not progress.

America’s classrooms still teach how to count money, but not how money counts. In other words, students must learn not just what to want, but how things work. The task ahead is not to silence emotion but to civilize it and to re-marry feeling with understanding. Only then can participation become judgment again, and citizenship recover its mind.

The surge in personal-finance mandates marks progress, but it has not yet produced citizens fluent in the language of governance. NAEP civics scores remain flat, PISA ranks the U.S. near the middle, and local politics drift from fiscal reality. Until economic and civic literacy become inseparable, America will continue to teach its children how to balance a checkbook, but not a democracy.

Questions Readers Often Ask

What does the “vibes economy” mean in today’s civic and political discourse?

The “vibes economy” is the tendency for emotions, narratives, and online cues to steer attention and behavior. It contrasts mood-driven engagement with participation grounded in how institutions work, budgets are set, and trade-offs are made.

Why are civics scores stagnant even as schools add civics or finance mandates?

Assessment results have flatlined because requirements often vary in depth, compete with limited classroom time, and emphasize testable facts or technical skills. Digital attention cycles favor reaction over reasoning, weakening durable knowledge of institutions.

How do identity-driven ‘vibes’ and personalities shape elections and policy debates?

Search interest clusters around recognizable figures, polls, and dramatic events. This personalizes complex issues, rewarding slogans and spectacle while crowding out process literacy—how laws are made, budgets allocated, or constraints negotiated.

How are civic education and financial literacy linked to effective democratic participation?

Both aim to build decision-making capacity. When taught in isolation, they produce narrow competence without context. Integrated instruction—budgets, trade-offs, and public finance basics—connects personal choices to institutional mechanisms.

Can practical, deliberative civics reduce mood-driven polarization and confusion?

Programs that pair media literacy with discussion, role-play, and community projects improve sense-making. They help students compare claims, evaluate constraints, and translate values into feasible policy, tempering emotion with institutional awareness.