Bargaining Under Asymmetry – Part 1: What Happened

Ukraine, the U.S., and the Geopolitical Fallout

Disclaimer: This report is intended solely for academic research and analytical purposes. It has been generated using AI-based analysis and may contain inaccuracies. The objective is to explore economic, geopolitical, and negotiation dynamics rather than to attribute responsibility or reach definitive conclusions. Readers should interpret this analysis as a conceptual framework rather than an authoritative account of events.

Introduction

In 2024–2025, negotiations between President Donald President Trump and President Volodymyr over Ukraine’s rare earth minerals became a focal point in a broader geopolitical struggle. The U.S., as Ukraine's principal military backer, wielded substantial leverage, while Ukraine faced existential security concerns. This report distills key findings from a detailed game-theoretic analysis of the negotiation, embedding it within NATO expansion, European security dynamics, and Russia’s counter-strategies.

➡️ President Trump’s 'transactional' approach pressured Ukraine into economic concessions in exchange for military aid.

➡️ President Zelensky had little leverage and sought security guarantees that were never fully granted.

➡️ NATO’s ambiguity left Ukraine in a weak negotiating position, while Russia exploited Western divisions, using hybrid tactics to deter deeper NATO involvement.

➡️ Europe’s military dependency on the U.S. meant it could not act decisively.

⚡ Outcome: Ukraine is facing significant economic concessions without securing explicit security guarantees, leading to ongoing uncertainty.

🔽 Click to Expand: Extended Introduction

Abstract:

This report analyzes the Trump–Zelensky rare earth minerals negotiation as a strategic bargaining game within the broader geopolitical context of NATO’s eastward expansion, Europe’s defense posture, France’s nuclear ambitions, and Russia’s counter-strategies. Using advanced game theory models and drawing on both Trump-era and Biden-era policies, we examine how asymmetric power dynamics, alliance commitments, and deterrence strategies shape the negotiation outcomes. Primary sources (official statements) and reputable analyses (think tank reports: RAND, CSIS, Brookings, ECFR) inform the discussion. We model the Trump–Zelensky mineral deal as a bilateral Rubinstein bargaining game with ultimatum tactics, set against a multi-player security dilemma involving NATO and Russia. We then explore three forward-looking scenarios: (1) a U.S. retrenchment from NATO under a Trump-like administration, (2) a peace deal where Ukraine cedes territory for NATO security guarantees, and (3) a more assertive French nuclear umbrella provoking Russian escalatory moves. The analysis identifies each actor’s Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA), evaluates signaling and commitment tactics, and assesses how different U.S. approaches (transactional vs. cooperative) influence European security and negotiation leverage.

Introduction:

In 2024–25, peace negotiations to end the Russia–Ukraine war became entangled with high-stakes resource diplomacy. The Trump administration pressed Ukraine to grant the U.S. extensive rights over Ukrainian rare earth and critical mineral reserves – a demand linked to U.S. wartime aid and future security guarantees independent.co.uk independent.co.uk. This Trump–Zelensky rare earth minerals negotiation represents a bilateral bargaining game with asymmetric power: the United States, as Ukraine’s principal military backer, wields outsized leverage, while Ukraine, fighting for survival, has limited alternatives. The negotiation’s outcome is further constrained by the broader geopolitical game between NATO and Russia, the collective action dilemmas in European defense, and emerging questions about nuclear deterrence in Europe’s security architecture.

This report conducts a strategic analysis of the Trump–Zelensky bargaining episode and its geopolitical linkages using game-theoretic concepts. We first dissect the one-on-one negotiation as a bargaining game, identifying each side’s strategy, payoffs, and BATNA. Next, we situate the bilateral game in a multi-actor setting: NATO’s expansion and security guarantees to Ukraine, Russia’s deterrence and coercive tactics, Europe’s military weaknesses and burden-sharing debates, and France’s attempts at nuclear leadership within NATO. We apply models such as the Rubinstein bargaining model for the Trump–Zelensky deal, Bayesian games for the incomplete information between NATO and Russia, and the collective action problem framework for NATO burden-sharing. Throughout, we contrast the Trump administration’s transactional, zero-sum approach with the Biden administration’s more alliance-focused, cooperative strategy to highlight policy impacts on the “game”. Finally, we explore three plausible scenarios and their implications for future negotiations and European security.

- Game Type: Bilateral bargaining with asymmetric power.

- President Trump’s Strategy: A transactional, zero-sum approach, conditioning U.S. military aid on economic concessions.

- President Zelensky’s Dilemma: With limited alternatives, Ukraine sought security guarantees in exchange for resource deals.

- Outcome: Ukraine is facing conceding partial access to rare earth revenues without securing explicit U.S. security guarantees.

🔽 Click to Expand: Full Bargaining Model Analysis

Game Type: Bilateral Bargaining with Asymmetric Power. The rare earth minerals deal can be modeled as a two-player bargaining game where the U.S. (under President Trump) is the stronger player and Ukraine (under President Zelensky) the weaker. The asymmetry stems from Ukraine’s heavy dependence on U.S. military aid and diplomatic support in its war against Russia, giving the U.S. substantial leverage to set terms. In game-theoretic terms, Trump holds a significantly higher discount factor (i.e. he can afford to wait or walk away) compared to Zelensky, who faces existential pressure to secure continued aid. This power imbalance allowed the U.S. side to issue take-it-or-leave-it offers akin to an ultimatum game, rather than engaging in prolonged equitable bargaining. The negotiation had a sequential nature: the U.S. would propose terms, and Ukraine could accept or reject, with rejection leading to punitive action (aid cutoff) from the U.S. side reuters.com reuters.com.

U.S. Strategy – Zero-Sum vs. Non-Zero-Sum: President Trump approached the negotiation in a highly transactional, zero-sum manner, framing U.S. support as a commodity for which Ukraine must “pay” in resources. Rather than seeing the U.S.–Ukraine partnership as a win-win alliance against Russian aggression, Trump treated it as a business deal: America would protect Ukraine only if compensated with a large share of Ukraine’s mineral wealth. In a leaked proposal, Trump demanded 50% of all revenues from Ukraine’s mineral and energy resources (including rare earth elements, oil, gas, etc.) plus veto power over Ukrainian mining licenses, in exchange for U.S. security guarantees after a peace deal independent.co.uk independent.co.uk. He explicitly stated that the U.S. is “no longer willing to provide free aid” to Kyiv and wanted “the equivalent of $500 billion” worth of minerals as payback for past and future supportrferl.org. This stance reflects a zero-sum mindset: any gain for Ukraine (continued U.S. aid or peace guarantees) must be matched by an equal or greater gain for the U.S. (ownership of resources).

Estimates place Ukraine’s total mineral wealth between $12–14 trillion, with rare earth elements and lithium alone valued at ~$11.5 trillion. These critical resources made Ukraine a strategic economic and geopolitical asset—one that Trump sought to leverage in negotiations (https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-ukraines-mineral-resources/)

President Donald Trump showed little interest in integrative solutions that could expand joint gains (e.g. long-term partnerships to develop Ukraine’s resources benefiting both countries’ security and prosperity). Instead, his rhetoric cast U.S. aid as a favor that entitled the U.S. to tangible Ukrainian assets rferl.org rferl.org. Such an approach risked undermining the alliance’s mutual trust: as Representative Adam Schiff criticized, “Are we to be nothing except transactional now? ... It’s all going to be about the money,” lamenting that the U.S. was betraying an ally and its principles for cash rferl.org rferl.org. By contrast, non-zero-sum (win-win) elements were scarcely present in Trump’s initial offer. Although the proposed deal mentioned U.S. investment in Ukraine’s reconstruction and future economyindependent.co.uk independent.co.uk, these were framed as vehicles to secure U.S. control (“joint investment fund” with U.S. first-refusal rights on licenses independent.co.uk) rather than genuine development aid.

Zelensky’s Strategy and BATNA: President Zelensky, in a vastly weaker negotiating position, initially attempted to push back against the most onerous terms. His Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) was extremely poor: without a deal, he risked losing U.S. military aid and political support, which could be catastrophic for Ukraine’s war effort. Nonetheless, Zelensky rejected Trump’s first draft outright because it lacked what Ukraine needed most – explicit security guarantees from the U.S. against continued Russian aggression csis.orgindependent.co.uk. Signing away half of Ukraine’s natural resource revenues for generations without ironclad assurances of U.S. protection would be “something that 10 generations of Ukrainians will have to repay,” as Zelensky reportedly said, refusing to sign on those terms independent.co.uk.

Zelensky’s negotiating strategy thus sought to transform the game from purely zero-sum to at least partially positive-sum by insisting on security guarantees (which would benefit Ukraine’s survival) as part of the exchange. He tried to link U.S. resource access to mutual gains – Ukraine’s security and a potential end to the war. However, given Trump’s reluctance, this was an uphill battle. Zelensky’s BATNA if talks collapsed was essentially continued war with diminishing aid, or attempting to rely more on European allies (whose military aid and security assurances, while significant, were not equivalent to U.S. support). As the game progressed, Zelensky’s fallback options narrowed: by early March 2025, Trump suspended all U.S. military aid and even intelligence-sharing to pressure Kyiv reuters.com reuters.com. This drastic move worsened Zelensky’s BATNA further – without U.S. targeting intelligence and weapons, Ukraine’s defensive capabilities would erode quickly. Facing this asymmetry, Zelensky signaled willingness to compromise: in a letter to Trump, he expressed readiness “to come to the negotiating table as soon as possible” and even to sign the minerals deal on Trump’s terms “at any time that is convenient”independent.co.ukindependent.co.uk. This capitulation in tone underscored that Ukraine had little alternative but to engage on Trump’s terms if the U.S. made its threat of abandonment credible.

Commitment, Ultimatums, and Signaling: The negotiation featured classic elements of brinkmanship and ultimatum strategies. President Trump effectively issued an ultimatum: Ukraine must accept the minerals-for-security deal or face the withdrawal of U.S. support. He demonstrated a willingness to carry out this threat by freezing vital aid and publicly berating Zelensky, making the cost of defiance painfully clear reuters.com reuters.com. By staging a shouting match in front of cameras at the White House and then halting aid, Trump sent a strong signal of resolve – a costly signal, since cutting aid could harm Ukraine (and risk backlash), but one that made his threats credible. In game-theoretic terms, Trump adopted a hard-line commitment strategy: he tied his hands by publicly insisting that Ukraine “owe” payment for American help, thereby making it politically difficult for him to back down without a deal. A White House official characterized the U.S. stance bluntly: the minerals concession was seen as the “first step to lasting peace” and implied that Zelensky had “overplayed his cards” by resisting independent.co.uk independent.co.uk. This language signaled that Washington believed Ukraine had no real bargaining chips and should acquiesce.

Zelensky’s approach to signaling was more constrained. He initially tried strategic ambiguity – stalling and counter-proposing rather than flatly refusing Trump. After rejecting the first draft, Zelensky did not simply walk away; his team quickly worked on a counterproposal that included explicit security guarantees, indicating Ukraine’s willingness to strike a deal if its core needs were met csis.org. He also invoked procedural delays (e.g. saying he needed Parliament’s approval to sign) to buy time csis.org. These tactics signaled that Ukraine was not rejecting the U.S. outright but needed a more balanced agreement. However, Zelensky’s leverage to make credible commitments or threats was minimal – any bluff that Ukraine might “go it alone” or turn elsewhere for aid was not credible. Instead, Zelensky’s strongest card was moral and political persuasion: reminding the U.S. and the world that Ukraine was fighting and bleeding for shared democratic values and regional stability. Indeed, he cautioned that without genuine security guarantees, any imposed deal could be untenable and “Ukraine will never exchange any status for any of our territories” (a signal that Ukraine couldn’t simply trade away sovereignty for vague promises)kyivindependent.com kyivindependent.com. Ultimately, as U.S. pressure escalated, Zelensky resorted to conciliatory signals – the letter expressing gratitude and readiness to sign independent.co.uk independent.co.uk – to try to repair relations and get the aid flowing again.

Outcome of the Bargaining Round: By March 2025, the hardball tactics appeared to force Zelensky to re-engage. Trump announced that Zelensky had sent a letter and was now “ready to sign” the revised minerals deal and work towards “a peace that lasts” under Trump’s terms independent.co.uk independent.co.uk. The U.S. side dropped some of its toughest demands (e.g. the explicit $500 billion upfront figure) to make the deal more palatableindependent.co.uk independent.co.uk. But crucially, security guarantees were still omitted from the agreement independent.co.uk, meaning Ukraine would be yielding economic sovereignty without the Article 5–like protection it sought. In game theoretic terms, Trump’s aggressive strategy succeeded in extracting major concessions – an equilibrium heavily skewed in favor of the stronger player. Ukraine conceded on the resource revenue split (agreeing in principle to ~50% in a joint fund) independent.co.uk independent.co.uk and on giving U.S. firms prime access, while the U.S. only “committed to back Ukraine’s economic development” in vague terms and paused its maximalist demand for $500B independent.co.uk. The negotiated deal (still preliminary) essentially reflected the “ultimatum game” outcome: the proposer (U.S.) taking a lion’s share of surplus, with the responder (Ukraine) accepting just enough to avoid complete loss of support.

However, this outcome, while perhaps a short-term Nash equilibrium under extreme power asymmetry, raised serious questions of sustainability. Zelensky’s acquiescence was coerced; the lack of genuine mutual benefit could breed instability (e.g. Ukrainian public resentment, as small protests in Kyiv against the deal indicated rferl.orgrferl.org). In repeated game terms, such an imbalance might erode trust for future cooperation. Indeed, observers noted that Russia was “delighted” by the spectacle – the public clash “shocked Europe and delighted Russia” abcnews.go.com – as it undermined Western unity and portrayed Ukraine as isolated. Thus, the bargaining game’s resolution fed into the larger strategic game, potentially weakening the Western coalition’s position vis-à-vis Russia. We now turn to that broader multi-player interaction.

- Multi-Player Strategic Interaction: NATO's eastward expansion and ambiguous security commitments influenced the President Trump-President Zelensky dynamic.

- Russia’s Response: Hybrid warfare, energy leverage, and nuclear posturing aimed to deter deeper NATO involvement.

- Ukraine’s Weak Bargaining Hand: NATO’s lack of immediate security guarantees constrained Kyiv’s negotiation leverage.

🔽 Click to Expand: NATO Security Dilemma and Russia’s Strategic Moves

Game Type: Multi-Player Strategic Interaction with Asymmetry & Incomplete Information. The Ukraine war and NATO’s involvement constitute a complex game among multiple players – NATO members (led by the U.S.), Russia, and Ukraine – with significant asymmetries (NATO’s collective power vs. Russia, and Russia’s local escalation dominance vs. non-NATO Ukraine) and incomplete information about each other’s red lines and resolve. Unlike the one-shot bilateral deal with Trump, this strategic interaction is ongoing and iterative, resembling a repeated game of deterrence intertwined with a Bayesian game of incomplete information. Each side has private information about its true willingness to escalate: NATO states signal how far they might go to defend Ukraine, and Russia signals how far it will go to stop NATO expansion and support for Ukraine. The uncertainty (e.g. will NATO intervene directly if Russia escalates? Would Russia use nuclear weapons if facing defeat in Ukraine?) forces players to continuously update beliefs and use signaling and brinkmanship to influence the other’s expectations.

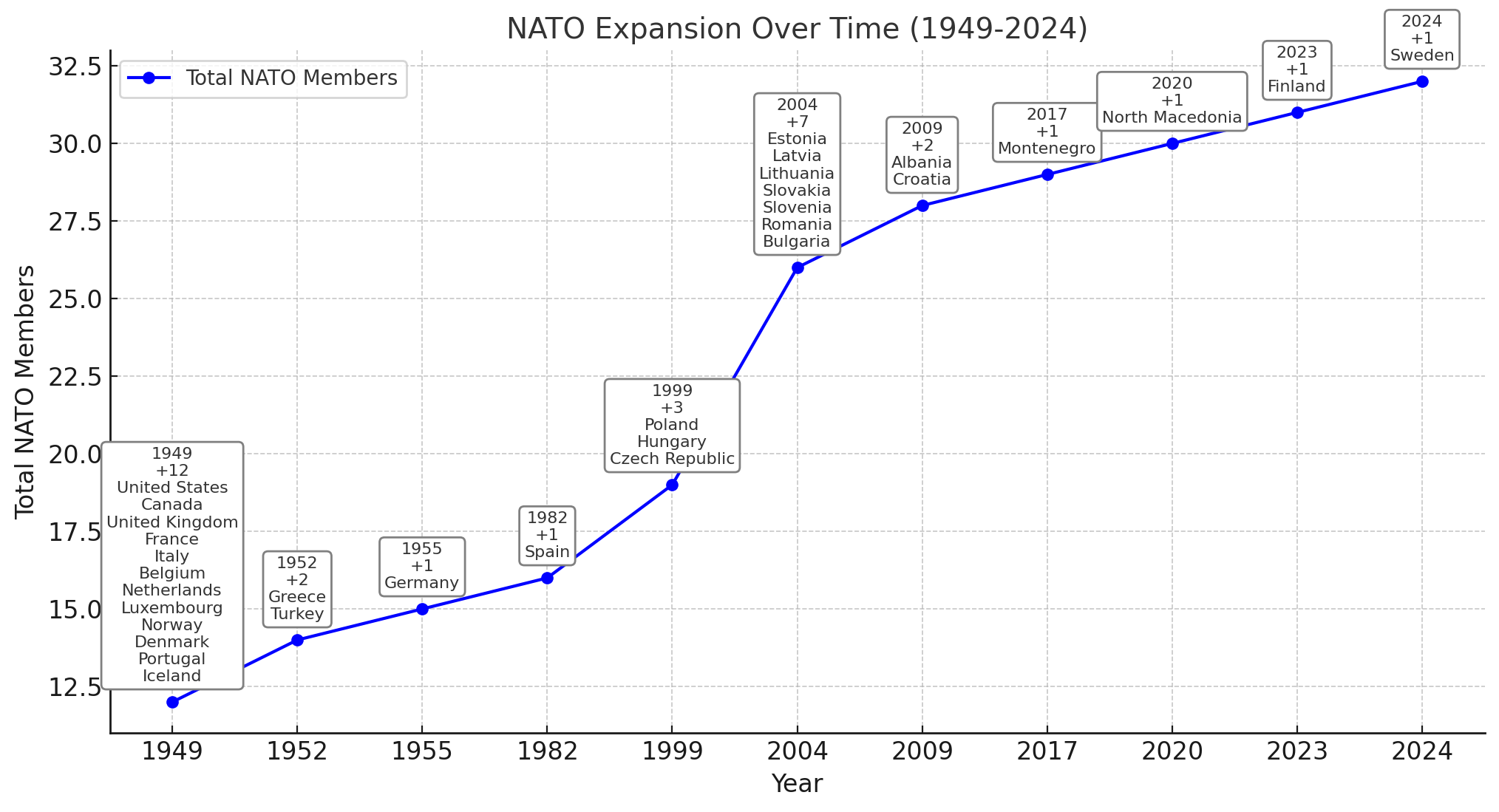

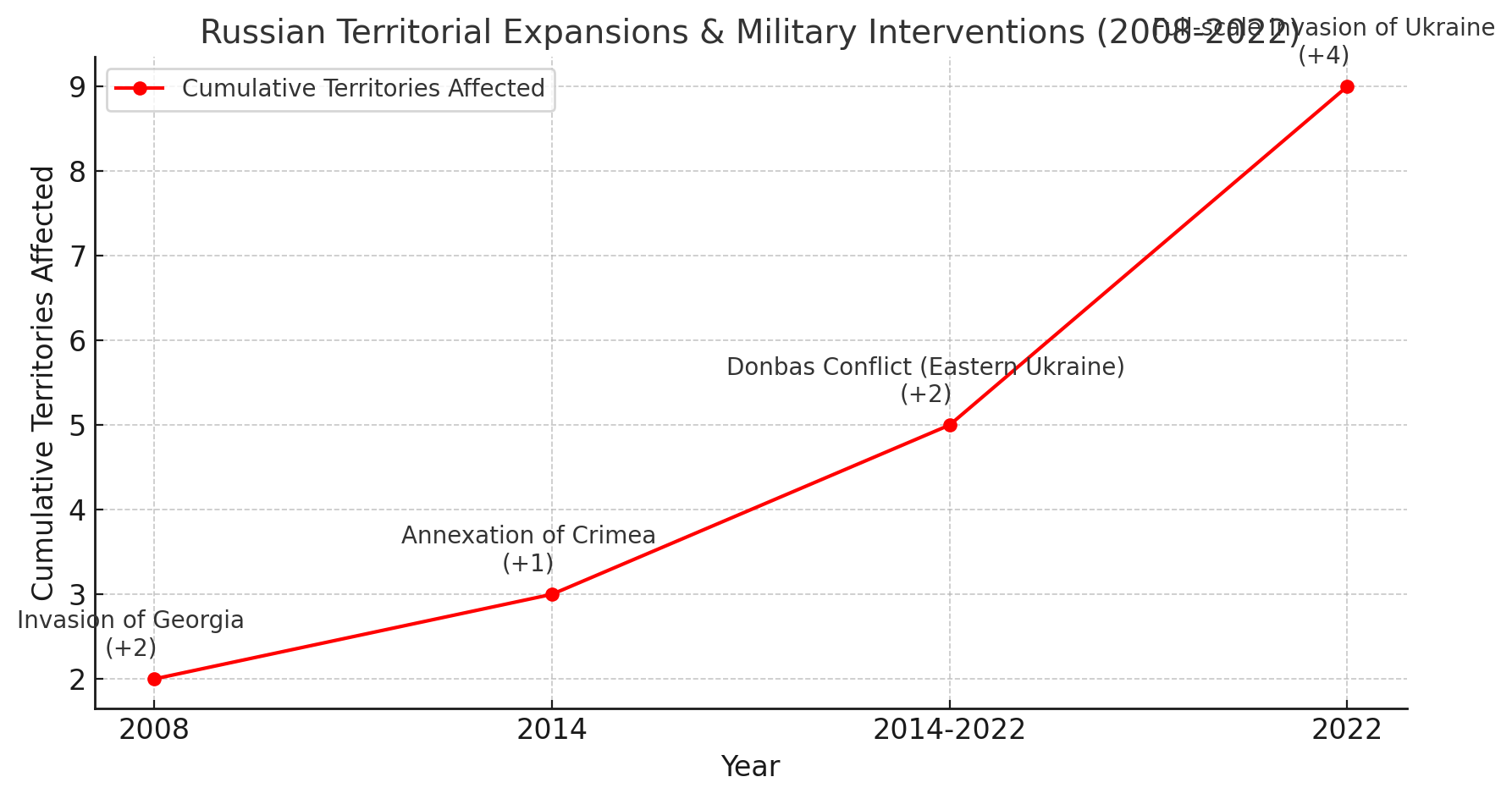

NATO’s Expansion Trajectory: Since the end of the Cold War, NATO has expanded eastward, admitting many former Warsaw Pact and Soviet republic nations. From Russia’s perspective, this was a unilateral gain in Western security at Russia’s expense – a classic security dilemma trigger. By 2022, NATO had moved right up to Russia’s borders in the Baltics and was politically committed (though not yet bound by treaty) to eventually admit Ukraine (and Georgia, as stated in NATO’s 2008 Bucharest Declaration). In 2022–2023, NATO further welcomed Finland (doubling NATO’s land border with Russia) and extended an invitation to Sweden, reinforcing the eastern flank. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s bid for NATO membership remained officially open but effectively frozen due to the active war and reluctance to provoke Russia into a larger conflict. This ambiguous status – neither under NATO’s Article 5 umbrella nor completely outside Western security assistance – significantly affected Ukraine’s bargaining power and Russia’s calculations.

For NATO, the expansion is seen as enhancing collective security and extending the zone of democratic peace in Europe. However, to Russia’s leadership, it represented a direct threat to Russian security. President Vladimir Putin and other Russian officials have for years signaled that NATO expansion into Ukraine would cross a “red line”. In early 2022, Russia cited Ukraine’s NATO aspirations and Western military support as primary justifications for its invasion afsa.orgecfr.eu. This suggests Russia viewed the situation as a game of Chicken: by invading, Putin aimed to force the West to back down on NATO expansion, betting that NATO would not directly fight to defend a non-member. NATO, in turn, had to balance deterring Russia from further aggression with avoiding a direct NATO–Russia war. This delicate balance created incomplete information: each side was uncertain how far the other would go. Would NATO ever intervene militarily if Russia’s onslaught threatened to overrun Ukraine? Conversely, would Russia dare attack a NATO member if it perceived NATO as divided or hesitant?

Ukraine’s Ambiguous NATO Status – Impact on Negotiation Power: Ukraine’s in-between status (a partner to NATO but with no Article 5 guarantee) severely weakened Zelensky’s hand both against Russia and in negotiations with allies. From a game theory lens, Ukraine lacked the credible guarantee that an outside force would retaliate if it were attacked or coerced – a guarantee that NATO membership provides to, say, Poland or the Baltic states. This made Ukraine a more attractive target to Russia (lower expected cost for aggression) and, simultaneously, a less secure ally from NATO’s standpoint (higher risk to promise full defense). Indeed, Putin exploited this ambiguity, treating Ukraine as a buffer whose alignment he could contest through war. Conversely, Zelensky’s leverage in bargaining with the U.S. or NATO for support was limited by the fact that Western leaders had not committed irrevocably to Ukraine’s defense. As seen with Trump’s negotiations, Ukraine could not fall back on a NATO treaty obligation, which might have prevented such an extreme transactional demand in the first place. Zelensky’s urgent pleas for a clear path to NATO (for example, at the July 2023 NATO summit) reflected his understanding that without formal guarantees, Ukraine remained vulnerable to being “bargained away” in great-power deals. Western leaders under Biden maintained an open-door policy but no timeline, effectively using strategic ambiguity: they kept Russia guessing about Ukraine’s long-term status, hoping to deter escalation while avoiding immediate conflict. This ambiguity, however, meant Ukraine had to keep proving its worth and pleading for support – a weaker negotiating position than a treaty ally’s.

Russia’s Deterrence Strategies and Countermoves: Facing a militarily superior NATO but driven by security fears and imperial ambitions, Russia has employed a range of deterrence and compellence strategies to counter NATO’s influence:

- Nuclear Posturing: Russia has repeatedly brandished its nuclear capabilities to dissuade NATO from deeper involvement in Ukraine. Within days of the 2022 invasion, Putin ordered Russia’s nuclear forces to a higher alert status, a signal to NATO of his willingness to escalate if NATO intervened directly ecfr.euinternationalaffairs.org.au. Throughout the conflict, Moscow (via Putin and senior officials like Dmitry Medvedev) issued thinly veiled threats of nuclear use if Russia’s core interests or territory were endangered. This behavior can be analyzed as an attempt to shape the Bayesian beliefs of NATO leaders – essentially telling them that the probability of Russian nuclear action is not negligible, hoping to deter moves like establishing a no-fly zone or fast-tracking Ukraine into NATO. In game-theory terms, Russia tried to shift the perceived equilibrium path towards one where NATO self-deters. This nuclear signaling had some effect: NATO (especially under Biden) calibrated its aid (e.g. initially hesitating on longest-range missiles and advanced tanks) to avoid crossing what it inferred might be Russia’s “red lines” for nuclear escalation. Only as the war dragged on and Western intelligence assessed a low likelihood of Russian nuclear use (given the immense costs) did NATO states incrementally increase military aid – an example of updating beliefs and adjusting strategy over repeated plays of the game.

- Hybrid Warfare and Ambiguous Aggression: Russia also used non-linear tactics below the threshold of open war with NATO to deter and punish allies. This includes cyberattacks (for instance, broad attacks on Ukrainian and even Polish cyber infrastructure), disinformation campaigns against NATO unity, covert operations and sabotage (such as the still-unattributed explosions on the Nord Stream gas pipelines in 2022, which many suspect Russia orchestrated as a message to Europe). These hybrid warfare tactics complicate the game by introducing uncertainty and allowing Russia to impose costs without triggering NATO’s collective defense. They serve as a form of deterrence by raising the pain of opposing Russia while maintaining plausible deniability to avoid full NATO retaliation airuniversity.af.edu historyoftheworlds.com.

- Energy Leverage: As a major gas and oil supplier to Europe, Russia historically has used energy exports as a geopolitical lever. In the context of the NATO-Russia-Ukraine game, Moscow sharply reduced gas deliveries to Europe in 2022–2023, hoping to create energy shortages and political divisions in NATO countries supporting Ukraine. By weaponizing winter fuel needs, Russia attempted to fracture the NATO coalition – a classic divide-and-conquer move in a multiplayer game. Europeans largely managed to find alternative supplies and conserve energy, blunting this leverage by winter 2023, but not without economic pain. The threat remains an element of Russia’s strategy: even in future negotiations, Russia might offer “energy relief” in exchange for concessions on Ukraine, testing NATO’s collective resolve.

- Conventional Military Posture Changes: In response to Finland’s NATO accession and heightened East-European defenses, Russia has pledged to reinforce its western and northern military districts, and deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus. These countermeasures are aimed at raising NATO’s expected costs for any potential future confrontation and deterring further expansion (such as deterring Sweden’s membership ratification and certainly dissuading NATO from any direct deployment in Ukraine). Essentially, Russia is trying to reestablish a buffer or at least a sense of mutually recognized spheres of influence, albeit by aggressive means.

The interplay of these strategies means the NATO-Russia interaction is akin to a multi-round deterrence game with elements of the security dilemma. NATO’s efforts to bolster Eastern Europe’s defense (such as deploying multinational battlegroups in Baltic states and Poland, and supplying Ukraine) are fundamentally defensive but are perceived by Russia as offensive threats, leading Russia to respond in ways (nuclear alerts, military buildup) that NATO then interprets as aggressive – a dangerous feedback loop thedefensepost.com thedefensepost.com. In theoretical terms, both sides are trapped in a partially zero-sum perception of security: one side’s gain is the other’s loss, fueling escalation. However, there is also incomplete information and signaling in play – each side occasionally looks for off-ramps or signals restraint (for example, the U.S. and NATO have carefully signaled what support they will not give Ukraine, like no NATO troops on the ground, in order to reassure Russia and avoid miscalculation). This can be seen as attempts to communicate and avoid the worst inefficient equilibrium (full NATO-Russia war).

Effect on the Trump–Zelensky Bargaining: The broader NATO-Russia game heavily influenced Zelensky’s bargaining power in the rare earth deal with Trump. Russia’s ongoing aggression and nuclear threats made Ukraine desperately dependent on external security guarantees, heightening Zelensky’s demand for any U.S. promise of protection. Trump’s willingness to consider a quick peace with Russia (he spoke of convening talks with Putin and downplaying NATO’s support independent.co.uk independent.co.uk) also altered the game: Russia likely perceived Trump’s stance as a strategic opening. Indeed, the Kremlin publicly gloated that the U.S. asking for minerals “demonstrated the US is no longer willing to provide free aid to Kyiv”, and simultaneously declared it was against Trump giving any help to Ukraine independent.co.uk. Tellingly, Putin even made a counter-offer: on Feb. 24, 2025 (the war’s anniversary), Putin invited the U.S. to jointly exploit Russia’s own rare earth reserves, pointedly noting Russia has “significantly more resources of this kind than Ukraine,” including in occupied Donbas rferl.org rferl.org. This move by Russia can be seen as an attempt to alter the “payoffs” in Trump’s game with Zelensky – effectively suggesting an alternative deal where the U.S. might benefit from minerals without supporting Ukraine. While the U.S. did not take up this offer, its mere proposal was a strategic countermove by Russia to undercut Ukraine’s position. It underscores how NATO’s adversaries (Russia) were actively manipulating the multi-actor game to influence the bilateral bargaining (Russia sought to incentivize U.S. retrenchment by dangling resource cooperation).

In summary, the NATO-Russia strategic interaction forms the backdrop that made the Trump–Zelensky negotiation so asymmetrical. NATO’s expansion and half-commitments left Ukraine in a dangerous gray zone, Russia’s countermoves intensified Ukraine’s security plight, and all players had to weigh any bilateral deal against the signals it sent in the larger game. Zelensky’s weak bargaining hand was a direct consequence of NATO’s inability (or unwillingness) to provide immediate, binding security guarantees – a collective decision influenced by fear of Russia’s responses. The next section examines Europe’s role in this equation, particularly how Europe’s own military weaknesses and diplomatic efforts shape the strategic landscape.

- Defense Spending Gaps: European NATO members historically relied on U.S. military contributions, limiting their capacity to independently support Ukraine.

- Diplomatic vs. Military Support: While European nations backed Ukraine diplomatically and financially, their military aid was insufficient to replace U.S. backing.

- France’s Nuclear Proposal: President Macron sought to position France as a security leader, offering an alternative deterrence framework for Europe.

🔽 Click to Expand: NATO Burden-Sharing and Europe’s Military Weaknesses

Game Type: Collective Action Dilemma & Free-Rider Problem within NATO. The European members of NATO collectively have significant military and economic power, but for decades they have relied disproportionately on U.S. defense contributions. This situation is a textbook collective action problem: all NATO countries benefit from the U.S.-provided security umbrella, creating an incentive to free-ride (let the U.S. bear higher costs), which many did. Prior to Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine, only 9 of NATO’s 29 members were meeting the agreed 2% of GDP defense spending target thedefensepost.com, leaving Europe under-prepared to counter major threats independently. This imbalance meant that when a security crisis like Ukraine arose, Europe’s ability to act without U.S. leadership was limited – a weakness apparent to both Washington and Moscow. In game theoretic terms, NATO Europe faced an n-player public goods game (collective defense as the public good) where each nation had an incentive to contribute less than optimal, assuming the U.S. (as the largest player) would cover the shortfall. President Trump’s frequent complaints about NATO allies being “delinquent” in defense spending and free-riding on U.S. taxpayers addressed exactly this issuethedefensepost.com thedefensepost.com.

Europe’s Military Dependence on the U.S.: European NATO countries, even the big economies like Germany, France, and the UK, entered the 2020s without the full spectrum of military capabilities needed for high-intensity warfare against a power like Russia. Key shortfalls included strategic airlift, advanced ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance), air and missile defense, adequate stockpiles of precision munitions, and in many countries, basic readiness of forces. The United States has long filled these gaps (e.g. U.S. satellites and drones for intel, U.S. Patriot and Aegis systems for missile defense, U.S. logistics for deployments). This dependence critically shaped the bargaining dynamics within NATO and with Ukraine. For Zelensky, it meant that European promises of support, while helpful, could not substitute for U.S. backing. Europe could supply arms (as the UK, Poland, and Baltics did generously) and money, but without U.S. heavy weaponry and coordination, Ukraine’s defense might have collapsed in 2022. Thus, Zelensky knew he ultimately had to secure U.S. support – giving Washington outsized influence over Ukraine’s fate.

Europe’s military weakness also emboldened Russia’s strategy. Prior to the 2022 invasion, Putin likely discounted European military intervention as extremely unlikely, an assessment that proved accurate. Even when European leaders like France’s Emmanuel Macron and Germany’s Olaf Scholz engaged Putin in intensive diplomacy (visiting Moscow, marathon phone calls) in early 2022, they carried a diplomatic stick that was not backed by a big military carrot. Russia might have perceived European diplomacy as lacking credible threat – Europe could urge or sanction, but not forcibly stop an invasion. This credibility problem is a typical weakness in deterrence games when one side’s commitments are not backed by capability. Indeed, Macron’s much-publicized shuttle diplomacy failed to deter Putin, and Scholz’s reported proposal in February 2022 of a neutrality deal for Ukraine to avert war was ignored or soon mooted by the outbreak of hostilities politico.eu eurotopics.net.

Diplomacy vs. Force – Europe’s Approach: Confronted with its relative military inferiority (vis-à-vis Russia’s local superiority and U.S.’s remote support), Europe often defaulted to diplomacy. During Trump’s presidency (2017–2020), key European powers also sought to preserve diplomacy because Trump’s commitment to NATO defense was uncertain. Europe was essentially hedging: strengthening sanctions and expressing support for Ukraine’s sovereignty, but also exploring negotiations with Russia. This was seen in initiatives like the Normandy Format talks (led by France and Germany, which brokered the Minsk ceasefire agreements) and later in 2019, President Macron’s call for a European rapprochement with Russia – controversially terming NATO “brain dead” and arguing Europe needed its own security dialogue with Moscow thedefensepost.com thedefensepost.com. Zelensky, newly elected in 2019, initially aligned with this European diplomatic approach, pursuing talks with Putin’s regime (e.g. a 2019 summit in Paris) to seek peace in Donbas. However, these efforts yielded limited results, partly because Russia did not take European leverage seriously.

The 2019 NATO London Summit was a revealing moment for Europe’s role and its influence on Zelensky’s strategy. At that summit, European leaders tussled with Trump’s antagonism toward NATO and Macron’s critique of alliance strategy thedefensepost.com thedefensepost.com. Trump harshly criticized allies like Germany and Canada for under-spending and even questioned the U.S. commitment if allies wouldn’t “pay their way.” This very public discord likely signaled to Zelensky that European security was only as strong as U.S. leadership allowed. Observing the London Summit, Zelensky would have seen that Europe alone could not guarantee Ukraine’s security if the U.S. wavered. Subsequently, Zelensky recalibrated – while engaging European support, he placed even greater emphasis on securing direct U.S. ties. Notably, in 2020 he sought a White House meeting (eventually happening under Biden in 2021) and in 2022, after war began, he persistently lobbied Washington for aid and a no-fly zone (knowing Europe couldn’t impose one without U.S.). In effect, the London Summit’s aftermath reinforced Zelensky’s bargaining strategy to not rely solely on European security structures. Europe’s diplomatic backing (strong statements, moral support) was valuable but insufficient; thus, when Trump in 2024 demanded a minerals deal, Zelensky found Europe had little immediate means to shield Ukraine from U.S. pressure. European Union officials could only offer tepid advice and “technical assistance” to Ukraine (as Lithuania’s ex-FM Landsbergis suggested Europe should at least help Kyiv evaluate the U.S. deal) rferl.org rferl.org, underlining Europe’s secondary role.

Trump’s NATO Burden-Sharing Critique and European Autonomy: President Trump’s constant critique – that Europe was freeloading and should do more – had a dual effect. On one hand, it pressured some European states to increase defense spending (e.g. allies did collectively raise defense budgets each year, and by 2024 more than nine allies met the 2% target, with many others on track). On the other hand, Trump’s unreliability spurred talk in Europe of strategic autonomy – the idea that Europe should develop the capacity to defend itself, reducing reliance on U.S. whims. This was championed especially by President Macron, who argued that Europe needs the ability to act independently if the U.S. “pivoted” away. However, achieving real autonomy is a long-term challenge. In the near term (2022–2023), Europe still needed U.S. leadership to respond to Russia’s war. When Biden took office in 2021, he reassured NATO of America’s ironclad commitment, temporarily quieting European autonomy debates. But Trump’s potential return (or a like-minded U.S. administration) kept alive European anxieties. This dynamic can be seen as Europe attempting to solve the free-rider problem by finally investing in the public good of defense – essentially to avoid being at the mercy of U.S. domestic politics.

The London NATO leaders’ meeting in Dec 2019 illustrated the costs of free-riding: Trump openly insulted allies (calling Trudeau “two-faced” over defense spending thedefensepost.com) and even warned that “Nobody needs NATO more than France,” suggesting that if the U.S. withdrew, France (and by implication Europe) would be in grave danger thedefensepost.com. Macron, in turn, insisted NATO needed a new strategy not just new spending – indicating European desire for a greater say. All this informed Zelensky’s calculus: he observed a NATO struggling with internal coherence. Europe’s security autonomy was (and remains) more aspiration than reality, yet Trump’s posture made it a pressing issue. For Zelensky, that meant European allies might not uniformly back a hard line against Russia if the U.S. signaled a different course. Indeed, as Trump pivoted to a conciliatory approach with Moscow in 2025, some Europeans grew uneasy but also relatively helpless: NATO’s official stance could only be as tough as its lead nation’s. European members could encourage Ukraine not to give in fully, but they could not compensate Ukraine for loss of U.S. support. This lack of independent capability to guarantee Ukraine’s security is the crux of the free-rider fallout.

Europe’s Influence on Zelensky’s Negotiation: European diplomacy did play a role in Zelensky’s strategy in subtle ways. For example, the July 2023 NATO summit in Vilnius (while hosted in Lithuania, it reflected European major powers’ consensus) stopped short of offering Ukraine membership, but provided a new NATO–Ukraine Council and language that Ukraine would join NATO once “conditions are met.” Although Zelensky publicly called the lack of a clear timeline “absurd,” he walked it back after consultations – likely at the urging of European allies who wanted to preserve unity kyivindependent.com. This indicates Zelensky heeded European diplomatic cues to maintain a united front. Later, in November 2024, Zelensky even floated an idea reminiscent of one voiced by a NATO official: accelerating NATO membership for the territory Ukraine still controls (implicitly accepting temporarily that occupied regions remain outside Article 5) kyivindependent.com kyivindependent.com. This idea – essentially partial NATO integration in exchange for ending the “hot” phase of war – shows European thinking rubbing off on Kyiv. It mirrored a suggestion (quickly retracted) by NATO’s Stian Jenssen that Ukraine cede some land for peace and membership politico.eupolitico.eu Zelensky had earlier called any land-for-membership notion “ridiculous”politico.eu, but facing strategic uncertainty after Trump’s election, he nuanced his stance to say if NATO would promptly protect currently free Ukraine, then diplomacy could try to recover occupied landkyivindependent.com kyivindependent.com. This shift implies that Europe’s “realist” diplomatic arguments – focusing on achievable outcomes like armistice lines and long-term security guarantees – influenced Zelensky when U.S. support looked shakier.

In conclusion, Europe’s role in this grand strategic game is paradoxical: economically and diplomatically significant, but militarily constrained. The collective action failure left Europe struggling to project strength, forcing reliance on U.S. decisions (and thus vulnerability to U.S. internal politics). This in turn undermined Ukraine’s negotiating leverage with both the U.S. and Russia. While European nations provided essential aid to Ukraine and maintained sanctions on Russia (diplomatic unity), their inability to offer Ukraine firm security guarantees or rapid NATO entry meant Europe could not alter the fundamental asymmetry Ukraine faced. Europe essentially acted as a supportive but secondary player – running to keep NATO unified, attempting talks with Putin, and after the Oval Office blow-up, expressing “dismay” at Trump’s treatment of Zelensky pbs.orgabcnews.go.com – but without the hard power to change the outcome. This realization has spurred new efforts (e.g. Germany’s rearmament, EU defense funds), but those will take time. Meanwhile, the gap is partly being addressed by one European power that does have unique capabilities: France, with its nuclear arsenal. The next section examines France’s bid for nuclear leadership and how it impacts NATO’s strategic balance.

🔽 Click to Expand: France’s Nuclear Leadership and NATO’s Strategic Balance

Game Type: Nuclear Deterrence Game & Questions of Strategic Credibility. When it comes to nuclear weapons in Europe, the dynamics can be analyzed as a deterrence game – essentially a high-stakes version of the game of Chicken, where credibility of threats is paramount. Within NATO, the United States has traditionally provided the “nuclear umbrella” through its strategic arsenal and forward-deployed nuclear bombs in Europe (under NATO nuclear sharing). France and the UK are the two European nuclear powers, but only France maintains an independent nuclear force not formally integrated into NATO’s command. As U.S. commitment became uncertain under Trump, and with Russia openly brandishing nuclear threats, President Emmanuel Macron positioned France’s nuclear deterrent as a possible backstop for European security. The strategic question is whether France’s offer to extend protection can credibly deter Russia and how it affects NATO’s overall deterrence posture and U.S. leadership in Europe.

Macron’s Nuclear Security Pledge – Content and Credibility: In February 2020, Macron gave a landmark speech inviting European partners to engage with France’s nuclear doctrine, effectively offering to “Europeanize” the French nuclear umbrella politico.eurfi.fr. More recently, amid Russia’s war and Trump’s potential return, Macron reiterated that France’s nuclear forces contribute to Europe’s security and that he is open to using France’s deterrent to protect the continent apnews.comrfi.fr. For example, in early 2024 Macron suggested an open debate on a European Union deterrent based on French nukes nipp.org, and reports indicated he even discussed this idea with Germany’s defense circles and potentially with Trump (had Trump won re-election, Macron was prepared to present a plan for European defense including the French nuclear umbrella) politico.eutelegraph.co.uk.

The credibility of Macron’s pledge is a complex issue. On one hand, France possesses a substantial (though much smaller than U.S. or Russian) nuclear arsenal – ~300 warheads with submarine-launched and air-launched weapons. France’s doctrine historically is “strict sufficiency” or minimum deterrence: the capability to inflict unacceptable damage to a major power, thus deterring existential threats to France. Macron has hinted that France’s “vital interests” have a European dimension, implying that a nuclear attack on a European partner might be seen as an attack on France newsweek.com. If European leaders and Moscow believed this, it could enhance deterrence. France also has sophisticated delivery systems and secure second-strike (sea-based), making its deterrent quite credible if it chose to use it.

On the other hand, doubts abound among allies and adversaries about whether France would truly launch nuclear weapons on another country’s behalf. During the Cold War, a famous question captured the doubt about extended deterrence: “Would the US trade New York for Paris?” (i.e. risk its own cities to defend Europe) politico.com. Now the question could be inverted: Would France trade Paris for Warsaw or Riga? It is one thing for France to threaten nuclear retaliation if France itself is struck; it is another to do so if, say, a NATO ally or Ukraine were struck, especially if the U.S. were less involved. Macron’s proposal lacks formal treaty basis and French leaders have carefully avoided an unconditional commitment. Indeed, France has traditionally guarded its autonomy – it did not join NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group and maintains independent control precisely so it is not automatically committed by others’ decisions. This makes collective decision-making a challenge: would Paris consult EU partners on a nuclear response? Macron opened the door to others “associating” with French nuclear exercises or discussions politico.eu politico.com, but this falls short of a clear guarantee.

Moreover, France’s stockpile size raises practical concerns: covering all of Europe under its umbrella might require a larger arsenal or at least a different targeting policy. Analysts note that to effectively deter Russia across the entire continent, France might need to expand its forces or shift from pure counter-value (cities) targeting to also threaten military targets, which it currently has limited capacity to do thebulletin.org politico.eu. Such adjustments are politically and financially non-trivial. There’s also domestic French skepticism: Macron’s overtures have been attacked by opposition parties at home as “selling out” French sovereignty to Europe politico.com. If a future French government (say Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, which is critical of sharing France’s nukes) comes to power, this embryonic offer could be withdrawn politico.com. These factors erode the credibility of France’s extended deterrence beyond its borders.

France’s Role in NATO’s Nuclear Umbrella and Effect on U.S. Leadership: Despite these questions, France’s move is strategically significant. It is essentially Western Europe’s contingency plan if the U.S. nuclear guarantee became unreliable. Under President Biden, the U.S. reaffirmed that “America’s commitment to Article 5 is ironclad,” maintaining U.S.-led nuclear deterrence as the cornerstone thedefensepost.com. However, if a Trump-like president reduced that commitment, European nations might look more seriously to Paris (and London, though the UK’s arsenal is partly dependent on U.S. tech and has been quieter on this issue). France’s nuclear outreach could somewhat reduce European panic in the face of U.S. ambiguity – providing a psychological reassurance that Europe is not defenseless. But it cannot replace the U.S. arsenal. As one European security researcher, Héloïse Fayet, observed, even combining France and the UK’s nuclear forces would not match the deterrent power of the U.S. politico.com. The U.S. has thousands of warheads and global delivery reach; France has hundreds and regional reach. Therefore, if U.S. leadership wanes, France’s role would likely complement but not fully substitute the U.S. role.

That said, an expanded French role could alter NATO’s internal dynamics. If European allies start coordinating more with France on nuclear strategy (e.g. including French nukes in NATO planning scenarios), the political center of gravity of NATO’s deterrence might shift slightly toward Europe. U.S. leadership could be “diluted” – perhaps NATO’s European pillar would gain a greater voice in nuclear policy. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, however, has pushed back against putting French nukes at the core of NATO strategy, emphasizing that NATO’s strength is its unity around U.S. extended deterrence rferl.org. This indicates institutional resistance to any move that might imply the U.S. umbrella is replaceable. Essentially, NATO as an organization does not want to signal any weakening of U.S. resolve, because that could invite Russian adventurism.

From Russia’s vantage point, a more prominent French nuclear role is a mixed development. On one hand, it means Europe is not completely helpless even if U.S. commitment faltered – Russia would still face a nuclear-armed opponent in any major aggression in Europe. On the other hand, Russia may calculate that France’s threshold for nuclear use is higher (due to the credibility issues discussed). Moscow might try to exploit any perceived gap between Washington and Paris. For instance, if Trump’s U.S. said it wouldn’t risk nuclear war over some Eastern European contingency, and France said vaguely it might, Russia could test that by escalating pressure on, say, the Baltic states, betting that France alone would hesitate to go nuclear without U.S. backing. This scenario is speculative, but it shows how an uncertain multilayered deterrence structure could invite Russian probing.

Russian Countermeasures to France’s Nuclear Posture: Thus far, Russia’s explicit reactions to Macron’s proposals have been muted publicly – likely because the concept is still abstract. However, we can infer likely countermeasures:

- Propaganda and Political Pressure: Russia will likely try to dismiss or divide Europeans over the French umbrella. For example, Russian state media could cast doubt: “Would Paris trade itself for others? Of course not,” aiming to weaken confidence in France’s pledge. They might also seek to influence French domestic debate (through disinformation or support for anti-NATO voices) to stymie Macron’s plan.

- Military Adjustments: If France were to formally extend its targeting to protect, say, Eastern Europe, Russia might react by repositioning its own nuclear forces. Already Russia has placed dual-capable Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad and is moving nuclear arms to Belarus. In a scenario of France leading a European nuclear scheme, Russia could increase the readiness or number of its tactical nuclear weapons in Western Russia, to ensure it could locally outperform a France-led response. It could also expand air defense and anti-submarine efforts against French nuclear delivery systems (like tracking French SSBN submarines more aggressively).

- Escalation in Crises: Paradoxically, if Russia perceives NATO-Europe as less backed by U.S. nukes and more by a hesitant France, it might take bolder action regionally, calculating that any nuclear retaliation is unlikely. This could raise escalation risks in a crisis, as Putin might underestimize Western response. For instance, in a Baltic standoff, Russia could employ a limited show of force (like a demonstration nuclear strike in an isolated area) expecting France (without U.S.) to seek negotiations rather than respond in kind. Such dangerous gambits are what NATO’s unified deterrence was designed to prevent by leaving no doubt that any nuclear use against NATO would trigger massive U.S. retaliation. A patchwork deterrence might reintroduce doubt in the adversary’s mind – exactly what one tries to avoid in deterrence theory.

From a game theory perspective, reliable nuclear deterrence requires a clear Nash equilibrium of no first use by making the cost of aggression astronomically high and certain. U.S.-led NATO deterrence aimed to make the threat of retaliation certain enough to be credible. A France-centered model introduces more uncertainty (higher entropy) in the opponent’s estimation of the retaliation probability. As Thomas Schelling noted, deterrence sometimes benefits from deliberate ambiguity, but only if backed by evident capability and some commitment. Here the ambiguity might cut the other way – the adversary might gamble that the deterrent threat is a bluff.

In sum, France’s nuclear leadership bid is an attempt to shore up a potential gap in NATO’s shield. It reinforces NATO’s deterrence to a degree, by adding another source of risk for Russia should it contemplate expanding the war or threatening Europe. However, it does not fully replace the depth and credibility of U.S. extended deterrence. If U.S. commitments wane, Europe may avoid total vulnerability thanks to France (and the UK), but the strategic balance in Europe could become shakier, with greater scope for miscalculation by Russia about Western resolve. NATO’s optimal outcome is still to keep the U.S. engaged while integrating French capabilities as a complementary layer – a multi-layer deterrence that leaves no opening for Putin’s desired wedge.

Having analyzed these thematic areas, we now turn to specific forward-looking scenarios that combine these dynamics in different ways. By exploring these scenarios, we can better understand the potential outcomes and policy implications for Ukraine and Euro-Atlantic security.

- Scenario 1: U.S. Reduces NATO Role

- Europe scrambles to increase defense spending.

- NATO faces potential fragmentation.

- Ukraine’s position weakens significantly.

- Scenario 2: Ukraine Accepts Partial Territorial Loss for NATO Membership

- Ukraine cedes some occupied territories.

- NATO accelerates membership for the remaining Ukraine.

- Creates a frozen conflict akin to Cold War divisions.

- Scenario 3: President Macron’s Nuclear Commitment Triggers Russian Countermoves

- France strengthens European deterrence.

- Russia escalates hybrid warfare and military posturing.

- NATO’s strategic balance shifts towards European-led deterrence.

🔽 Click to Expand: Detailed Scenario Analysis with Game-Theoretic Modeling

Based on the above analysis, we examine three hypothetical scenarios that test different configurations of U.S. commitment, Ukrainian concessions, and European deterrence initiatives. In each scenario, we outline the strategic gameplay, likely actions of key players, and potential outcomes.

Scenario 1: U.S. Reduces NATO Commitments under a Trump-like Administration

Assumptions: The U.S. significantly downgrades its NATO role – for instance, a President Trump (or similar leader) in 2025 stops all military aid to Ukraine, pulls back U.S. forces from Europe, or even threatens to leave NATO if allies do not meet demands. The U.S. remains formally in NATO but its security guarantees become ambiguous at best.

Strategic Dynamics: This scenario would throw NATO into a classic collective action crisis. Europe would face the immediate need to provide its own security (the public good the U.S. had supplied). In game terms, the “largest player” (U.S.) exiting forces the remaining players to either massively increase their contributions or see the good (deterrence) undersupplied. Initially, such a scenario likely yields instability: European allies would scramble to boost defense spending and create alternative arrangements, but these take time. Russia, noting NATO’s weakened cohesion, might test the waters – perhaps not by outright attacking a NATO state (still risky), but by increased coercion. For example, Russia could escalate hybrid attacks on the Baltic states or increase military incursions, expecting a slower, less unified NATO response. The deterrence game shifts toward Russia’s favor due to the perceived vacuum of U.S. power.

There is also a real risk of NATO political fracture. If the U.S. explicitly questions Article 5, frontline states like Poland and the Baltics might seek unilateral security guarantees elsewhere (e.g. bilateral deals with the UK/France or regional pacts). Countries less exposed to Russia might be tempted to accommodate some of Russia’s demands to avoid conflict. This aligns with the “partial US disengagement” scenario analyzed by strategic think tanks, who warn it could lead to a “two-tier” NATO or tempt Russia to probe weaknesses newsukraine.rbc.ua. Historically, U.S. presence has been the linchpin of NATO credibility; without it, the alliance’s equilibrium could shift from strong mutual defense to a much looser form, undermining deterrence.

European Response: Europe would try to convert this into a burden-sharing game where they belatedly fulfill what Trump asked: higher defense spending, perhaps a European collective defense initiative. The EU or a core group (France, Germany, Poland, etc.) might push for a “European Defense Union” more seriously, pooling resources. France would certainly push its nuclear umbrella as a key pillar (maybe the only pillar if U.S. nukes are no longer guaranteed). In time, Europe could emerge more militarily self-reliant – if political will and coordination hold. But in the short term, gaps in capabilities and divergent threat perceptions could hinder a quick fix. For instance, Southern European countries might be less willing to divert massive funds to deter Russia compared to Eastern ones, causing intra-EU rifts (a smaller scale free-rider problem within Europe itself).

Outcome for Ukraine and Eastern Europe: Ukraine would be in dire straits in this scenario. If the U.S. cuts off aid and NATO is paralyzed, Ukraine may have no choice but to seek a ceasefire or peace on Russia’s terms to survive. Zelensky or Ukraine’s leadership could find themselves forced to negotiate from a position of extreme weakness, potentially freezing the conflict with significant territorial losses and minimal guarantees. Europe might continue some support, but Europe alone (even if willing) may not sustain the intensive level of military aid the U.S. was providing. Alternatively, a few European states (e.g. Poland, Baltic nations) might unilaterally step up involvement (some have even floated the idea of a European “coalition of the willing” peacekeeping force if the U.S. retreats independent.co.uk). However, without U.S. backing, such moves would be risky and limited.

In essence, Scenario 1 risks fulfilling one of Putin’s objectives: decoupling the U.S. from European security. NATO facing an “immediate crisis” of credibility was indeed anticipated if Trump had won – analysts predicted “a weakened or even unraveling NATO” newsweek.compolitico.com. The likely equilibrium is a more insecure Eastern Europe and a Russia that, while still deterred from direct NATO invasion (due to residual French/UK deterrence and the fact that attacking NATO could still unify it), gains greater leverage to intimidate and influence its neighbors. Over time, Europe could adapt and form a new balance of power, but that interim could be chaotic. The key policy takeaway is that preventing this scenario – by bolstering European defense now and maintaining U.S. engagement – is crucial. Indeed, recognition of this risk has already driven European NATO members to increase defense budgets in 2022–24 and explore new capabilities, as a hedge against a future U.S. strategic retrenchment newsukraine.rbc.ua.

Scenario 2: Ukraine Accepts Partial Territorial Loss for NATO Security Guarantees

Assumptions: Faced with protracted stalemate and wavering Western unity, Ukraine agrees to a peace deal where it cedes some occupied territories to Russia (e.g. the Crimean Peninsula and parts of Donbas) in exchange for a binding security guarantee from NATO or major powers for the remainder of its territory. This could take the form of accelerated NATO membership for “Free Ukraine” (areas under Kyiv’s control), or a formal defense treaty with the U.S. and key allies, short of full NATO accession.

Rationale: This scenario reflects the idea (floated by some Western officials and analysts) that a partition-like compromise might end the war and secure peace for most of Ukraine politico.eubrusselstimes.com. It draws historical analogy to West Germany joining NATO in 1955 while East Germany remained under Soviet control – NATO’s Article 5 applied only to the West. In mid-2023, a NATO official’s suggestion along these lines sparked controversy politico.eupolitico.eu, but by late 2024 Zelensky himself hinted that if NATO would “quickly take under NATO umbrella the territory… under our control,” then Ukraine could pursue regaining the rest diplomatically kyivindependent.com kyivindependent.com. This indicates that under extreme pressure, Kyiv might consider this trade-off.

Strategic Outcomes: If implemented, Ukraine (let’s say roughly 80% of its pre-2014 territory) would come under explicit NATO protection. This would greatly strengthen deterrence for that portion – Russia would be extremely unlikely to attack NATO-guaranteed Ukraine, knowing it would trigger war with NATO. In theory, this could freeze the conflict lines similarly to how the Korean War armistice line has become a de facto border – an undesirable outcome morally (legitimizing aggression) but one that stops the bloodshed and secures a non-Russian future for the remaining Ukraine. Ukraine would essentially be sacrificing territory for certainty and peace.

However, such a scenario poses serious credibility and moral hazard issues. Firstly, NATO would need to be absolutely clear and unanimous in extending Article 5 (or an equivalent pact) to Ukraine. If some NATO members quietly dissented or imposed caveats (to avoid direct conflict with Russia in case of flare-up), Russia might see an opening to erode that guarantee. Assuming NATO does fully commit, the line of contact would become a new East-West frontier. Russia could respond by heavily militarizing the newly gained/held territories and possibly annexing them formally (as it claimed to annex several oblasts in 2022). We’d likely see a heavily fortified border in Donbas akin to the DMZ in Korea, with Russian forces on one side and NATO/Ukraine forces on the other.

For Russia, this scenario is double-edged. On one hand, it gains territory – consolidating control over Crimea and parts of Eastern Ukraine, which Putin could sell as a victory. On the other hand, it loses the rest of Ukraine definitively to NATO, exactly what it tried to prevent. Would Russia accept this outcome? Possibly only if its military position deteriorates to a point where continuing the war threatens even worse outcomes. It might also bank on the long-term chance to destabilize “NATO-Ukraine” from within or undermine the agreement politically.

One risk is future escalation over the “lost” territories: Ukraine would never legally recognize the ceded regions as Russian (just as West Germany never recognized East Germany or the loss of Königsberg). With a NATO guarantee, Ukraine might be constrained from attempting military reconquest (NATO would forbid offensive action from its territory to avoid war), but that lingering irredentism could fuel conflict down the road or become a permanent grievance. In effect, this scenario freezes the conflict but doesn’t fully resolve the Russia-Ukraine dispute – it transforms it into a long-term Cold War-style standoff at a fixed line.

From a game theory viewpoint, this could be seen as achieving a stable equilibrium in the short-to-medium term through a clear partition and alliance commitment, but it’s an equilibrium of mutual deterrence rather than cooperation. It prevents worse outcomes (further invasion of Ukraine or endless war of attrition) by drawing a line both sides fear to cross.

Precedents and Feasibility: The closest precedent is indeed Cold War divisions (Germany, Korea). Notably, West Germany’s NATO entry did help secure it, but reunification took 45 more years and only occurred when the adversary (USSR) collapsed. Ukraine might face a similar multi-decade division. Politically, it would be a bitter pill: Zelensky’s government has repeatedly said no territorial concessions and “Ukraine will never exchange territory for status” kyivindependent.com. Accepting such a deal could be domestically explosive unless the population is exhausted by war and sees no alternative. It might even require a change in leadership or a public referendum. Conversely, NATO states would also have to swallow the idea of rewarding aggression with land – something they have avoided thus far. There’s also the legal worry: how to ensure Russia honors the deal and doesn’t simply use the breather to rearm and attack later (as happened after Minsk agreements)? That’s why locking Ukraine into NATO is crucial in this scenario – it raises the cost for Russia to break the peace.

If done under U.S. auspices (perhaps a future U.S. administration brokering it), that security guarantee would have to be extremely explicit. Another form could be a U.S.-UK-France security treaty with Ukraine (short of NATO membership but perhaps akin to an “Article 5-like” pledge). In fact, the G7 nations offered in 2023 a framework for long-term security assistance to Ukraine, to be formalized in bilateral agreements – a kind of quasi-guarantee to deter Russia from renewing war after a ceasefire. This is a step in that direction but not as strong as NATO membership.

International Impact: Such an outcome might actually relieve NATO of the immediate Ukraine burden (once Ukraine is secured and the active fighting stops). But it sets a precedent that large-scale aggression can yield some gains (Russia keeps territory). China and others would watch that precedent – a concern NATO has voiced in justifying why Russian aggression must not be rewarded. The credibility of international law takes a hit, but NATO could claim it ultimately defended what it could and saved a country from complete subjugation.

In summary, Scenario 2 is one of grim compromise: a partially successful defense for Ukraine. It solidifies the West vs. Russia boundary farther east than before, at the cost of Ukrainian territorial integrity. For Zelensky (or his successor), it would mean betting fully on NATO protection for a smaller Ukraine in exchange for ending the carnage. For NATO, it means expanding to Ukraine (a long-term goal) under adverse circumstances, increasing NATO’s direct frontier with Russia. For Russia, it means settling for a piece of Ukraine, abandoning the rest to NATO – a strategic setback disguised as a tactical win. Whether this scenario materializes will depend on battlefield developments and Western unity; it could become attractive if a military stalemate endures and U.S. domestic politics impede an outright Ukrainian victory. It’s essentially a negotiated equilibrium point between the status quo and maximalist aims on either side.

Scenario 3: Macron’s Nuclear Commitment Triggers Russian Escalations

Assumptions: France takes concrete steps to extend its nuclear deterrent over Europe – for instance, explicitly stating it would retaliate against any Russian nuclear strike on European soil, or conducting joint nuclear exercises with other EU states. This new posture is broadcast as a response to a perceived decline in U.S. reliability. Russia, viewing this as a provocation or threat to its strategic position, reacts with escalatory measures.

French Moves: In this scenario, suppose Macron (or a successor continuing his policy) formalizes the offer of a European nuclear umbrella. Perhaps France announces an extended deterrence doctrine that covers EU/NATO allies, or invites German or Polish liaison officers into its nuclear command structure to signal shared use. France might also raise the readiness of its nuclear forces, or increase warhead stockpiles, to add credibility. Maybe even the idea of basing French nuclear warheads in another EU country (though that would be a huge departure and likely remains hypothetical). These actions aim to fill any gap left by a temperamental U.S. and to dissuade Russia from nuclear blackmail.

Russian Escalation: Russia’s likely escalatory responses could be:

- Rhetorical and Diplomatic Escalation: Moscow could loudly denounce France’s move as destabilizing. It might declare that French nuclear assets become prime targets for Russian missiles. It could break off any remaining arms control dialogues. Possibly, Russia would withdraw assurances like the 1994 Budapest Memorandum (which it already violated in Ukraine) vis-à-vis any other states. This is mostly rhetorical since tangible arms control is already scant.

- Military-Technical Escalation: More seriously, Russia could deploy additional nuclear forces in threatening ways. For example, it might move nuclear-capable Iskander missiles into Belarus or Kaliningrad permanently (if not already) and explicitly announce they are aimed at “European decision centers”. It could resume nuclear testing (if it withdraws from the CTBT de facto or actually, as has been hinted). Russia could also increase the number of strategic bomber flights near European airspace or simulated nuclear strike exercises to signal readiness.

- Doctrinal Lowering of Threshold: Russia might adjust its nuclear doctrine publicly to a more aggressive stance, such as emphasizing pre-emption. (Current Russian doctrine allows nuclear use if the state’s existence is threatened. They could claim an expanded view that a French nuclear incorporation of Europe threatens their existence, thus justifying a hair-trigger.) This is dangerous, as it could miscalculate Western intentions, but it’s about signals: essentially matching French extended deterrence with a more menacing Russian posture.

- Proxy or Regional Escalation: Outside the nuclear realm, Russia could escalate in other theaters to pressure France/Europe. For instance, Russia might intensify conflicts in Syria or Africa where French interests lie, as retaliation. Cyber escalation is also likely: attempting to disrupt French command and control or European infrastructure as a show of force (without crossing into kinetic conflict).

In pure strategic terms, if France’s extended deterrent is seen as credible, Russia is still deterred from direct attack on NATO as before. The escalations would thus likely be demonstrative or tangential – raising fear and costs but stopping short of actual use of nuclear weapons against NATO. However, the risk of miscommunication or accident increases with more forces on high alert and more aggressive posturing on both sides. The margin for error shrinks, akin to how the Cuban Missile Crisis arose from Soviet deployments reacting to perceived imbalance.

NATO Unity Impact: Macron’s nuclear foray could also cause internal NATO tensions that Russia could exploit. The U.S. might perceive it as undermining the primacy of U.S. extended deterrence. Some European nations (especially those under the U.S. nuclear sharing program like Germany, Italy, Turkey) might be unsure how French assurances integrate with U.S. ones. If Russia escalates threats specifically against France or say Germany for collaborating, NATO would have to decide if an attack on France (for example) is met with full alliance response – theoretically yes, but if it’s nuclear, then it’s existential. In essence, Russia could try to single out France (or any European power going along with this nuclear plan) and intimidate others into distancing themselves. For example, Russia could announce that countries hosting French nukes (if that happened) would become nuclear targets, hoping that fear would make those countries reject the French plan.

Possibility of Nuclear Brinkmanship: In a severe crisis triggered by, say, a Russian move on the Baltics or a conflict over a miscalculation in Ukraine, a France-backed deterrence might be tested. If Russia threatened a limited nuclear strike in Eastern Europe and France (with or without full NATO) threatened nuclear retaliation, we’d have a classic brinkmanship scenario. The side that convinces the other it’s willing to go one step further “wins”, but if neither blinks, catastrophe ensues. Without the U.S. as the overwhelmingly dominant nuclear power, this brinkmanship could be more unstable because the balance of destruction, while still massive, is less one-sided than U.S vs Russia. (Russia might think it can strike a European target without hitting America, and maybe America would stay out; France would have to prove that any strike on Europe means full-scale nuclear war anyway.)

While this scenario is extreme, it highlights that a European nuclear deterrent strategy could inadvertently invite a nuclear crisis if not carefully managed within the broader NATO context. It essentially creates a tripwire of its own – if Russia crosses certain lines, France (and whoever supports it) must act or lose credibility, which then triggers Russian responses.

Outcome: Ideally, even with escalations, rational actors would pull back before actual nuclear use. We might see a new uneasy equilibrium with more nuclear weapons in Europe pointed at each other, reminiscent of the early 1980s before the INF Treaty – but now with France and the UK more explicitly part of the equation, not just U.S. vs USSR. Strategic stability might eventually be regained by negotiations (for instance, Russia and France/UK might need to set up bilateral understandings or confidence measures, since previous arms control was U.S.-USSR/Russia only). In the worst case, misperceptions could lead to a limited nuclear exchange – which would be a humanitarian and ecological disaster beyond any acceptable outcome. That’s why both sides would likely be very cautious even as they escalate signals.

In summary, Scenario 3 warns that increasing the number of nuclear decision centers (Washington, Paris, London, Moscow, perhaps Brussels in a political sense) can complicate deterrence. If not done in unity, it could be divisive or provoke stronger threats. For policymakers, this scenario underscores the importance of maintaining dialogue with Russia even as NATO adjusts its deterrence, to avoid unintended escalation. It also implies that any French-led nuclear arrangement should be embedded within NATO strategy (with U.S. support if possible) to minimize confusion – a point Stoltenberg emphasized rferl.org. Russia’s likely aggressive responses should be anticipated and met with both resolve and offers of arms control talks to prevent a new nuclear arms race in Europe.

Lessons and Strategic Implications

This analysis highlights the complex interplay of power dynamics, strategic signaling, and broader NATO-Russia interactions that shaped the President Trump-President Zelensky bargaining episode. Europe’s challenges in coordinating collective defense influenced Ukraine’s position, while shifting U.S. diplomatic approaches introduced uncertainty in alliance commitments. Moving forward, the stability of NATO’s security framework will depend on how effectively it adapts to evolving geopolitical pressures and internal cohesion.

🔽 Click to Expand: Detailed Lessons and Strategic Implications

The Trump–Zelensky rare earth minerals negotiation, when examined through advanced game theory and set against the panorama of NATO’s evolution and Russia’s reactions, provides critical insights into alliance dynamics and bargaining under duress. It demonstrated how a dominant power can leverage asymmetric dependence to extract concessions (as Trump did with Ukraine), but also how such zero-sum tactics can strain the moral and strategic fabric of alliances. The broader context – NATO’s expansion and Russia’s aggressive countermoves – shows the interplay of deterrence and assurance, incomplete information and signaling, that define European security. Europe’s internal collective action problems have real consequences: insufficient investment in defense forced Ukraine into a vulnerable spot and limited Europe’s ability to influence events except through U.S.-led structures. France’s proactive stance suggests possible remedies for European autonomy, but also carries its own risks and requirements for credibility.

In policy terms, several recommendations and observations emerge:

- Maintain Credible Commitments: Whether in bilateral aid deals or collective defense, credibility is king. The turbulence of Trump’s approach taught allies (and adversaries) that U.S. guarantees can fluctuate. Re-establishing bipartisan reliability in U.S. commitments (as the Biden administration has attempted with NATO) is vital to deter adversaries like Russia and to avoid destabilizing transactional episodes. Conversely, if a U.S. leader seeks deals like the rare earth pact, they must also consider the long-term costs: short-term gains can undermine the very alliance cohesion and principles that give the U.S. leverage. A more cooperative negotiation could have found positive-sum outcomes (e.g. joint resource development plus solid security for Ukraine) rather than public bust-ups that benefit Russia’s narrative.

- Strengthen European Defense and Unity: The analysis of the free-rider problem and Scenario 1’s dangers reinforce that Europe cannot remain a weak link. Recent moves to increase defense budgets, develop EU defense initiatives, and coordinate procurement should continue aggressively. Europe needs to be prepared in case U.S. support falters in future – a form of self-help to ensure that Putin or his successors cannot exploit a leadership vacuum. However, this should be done in complement to NATO, not in competition. A strong Europe within NATO will actually shore up the alliance and make any future “Trumpian” bargaining position less coercive (because Europe could carry more weight of the response).

- Smart Use of Game Theory in Diplomacy: The actors in these events would benefit from the systematic thinking game theory provides. For example, identifying BATNAs clearly can prevent overreach – Trump overestimated his BATNA if cutting off Ukraine would have led to Ukraine’s collapse or a larger war that might drag the U.S. in later. Likewise, Putin underestimated NATO’s resolve in 2022, misreading signals and ending up with a worse strategic position (Finland in NATO). Simulation of scenarios (as done in think tanks clingendael.org) should inform diplomatic strategy: e.g. how to offer Putin an off-ramp that he might actually take, or how to assure Ukraine security without provoking Russia to desperation. Concepts like security dilemma sensibility (recognizing the other side’s insecurity) could have tempered NATO’s approach to Ukraine, perhaps finding a formula to bolster Ukraine without triggering Russia – though ultimately responsibility lies on Russia for choosing war.

- Innovate Security Guarantees: One clear message from Zelensky’s plight is that ambiguous promises are dangerous. The West may need to craft new forms of security guarantees for partners like Ukraine that fall short of full NATO membership but are stronger than political assurances. This could involve defense pacts or embedding advisors/forces in partner militaries as tripwires, to raise the cost of aggression. The failure of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum (where Ukraine gave up nukes for vague guarantees) is stark – future guarantees must be backed by capability and will. If Scenario 2 or some variant occurs, those guarantees must be unambiguous and long-term.