The Question Is Not Whether America Can Still Afford to Lead

Beyond Defense: The Structural U.S. Deficit and the Untaxed Wealth Gap

The debate over U.S. defense spending has taken on new urgency. Critics on both the left and right argue that Washington overspends on its military and alliances—particularly NATO—at the expense of fiscal stability. Meanwhile, China is tightening bonds with Russia, Nicolás Maduro’s Venezuela, and even North Korea in a revival of anti-U.S. bloc politics. These developments raise a hard question: how can the U.S. sustain global commitments without undermining its alliances in Europe or hollowing out its domestic base?

The answer lies not only in spending choices, but in the structure of U.S. federal revenue.

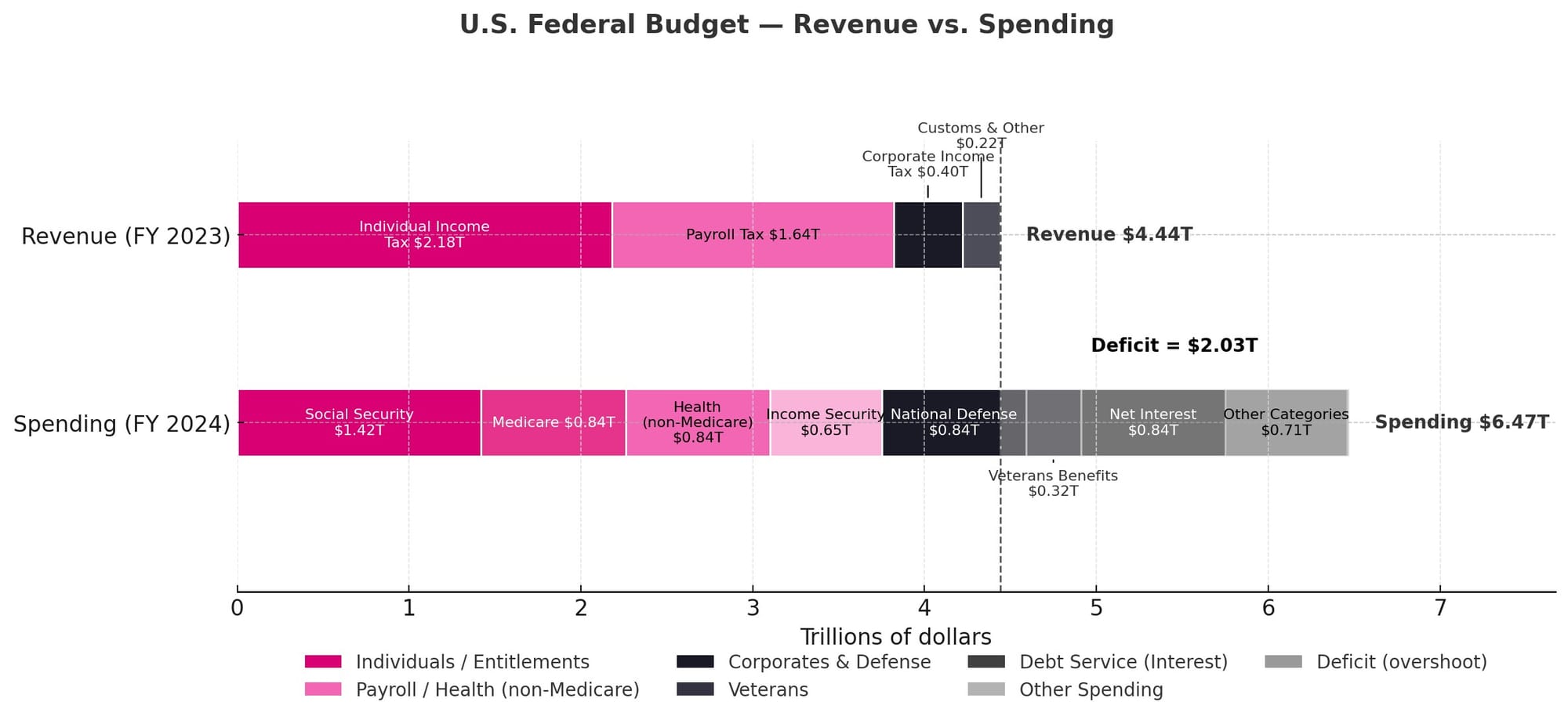

Federal revenues—primarily from individual income taxes (≈49%) and payroll taxes (≈37%)—are almost entirely consumed by mandatory entitlement programs (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid). Once a baseline of defense is added, the federal ledger is essentially out of cash.

Everything else—expanded defense, veterans’ benefits, infrastructure, education, and discretionary programs—is financed with debt. That gap between revenue and spending is the structural deficit.

Sources: Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Budget and Economic Outlook FY2024; Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Historical Tables.

Why Defense Still Gets the Spotlight

Defense spending is the most visible line item: carrier groups, NATO exercises, missile defense. Cutting defense in isolation will not close the structural gap. What the U.S. faces is not a NATO problem, but a tax system problem: revenues plateau while obligations expand.

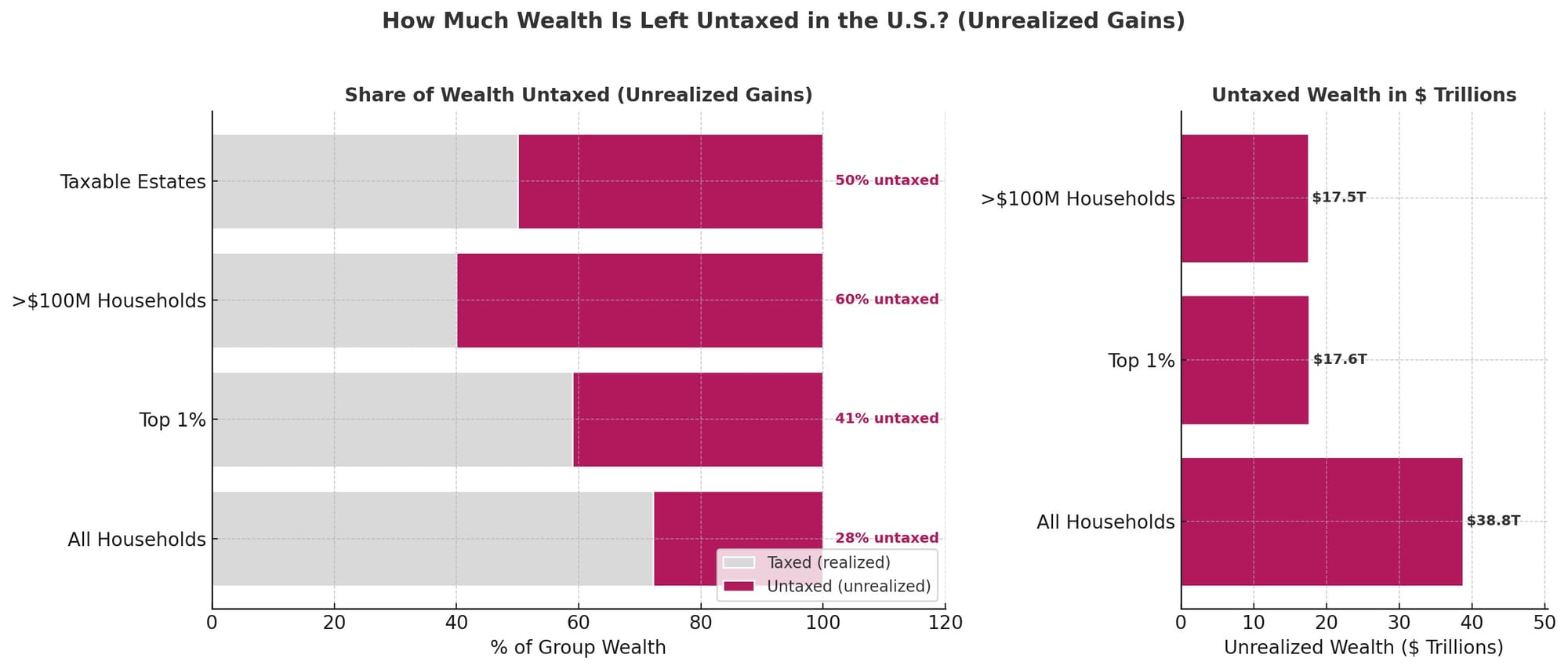

The United States finances deficits through debt while leaving vast stores of private wealth untaxed: unrealized capital gains.

- Across all households, ~27–28% of wealth is unrealized gains, ≈ $39T in 2023.

- For the top 1%, ~41% of their wealth is unrealized, ≈ $17.6T.

- For households worth over $100M, more than half of their wealth (≈60%) is unrealized.

The unresolved question was: how much of the national $39T in untaxed gains belongs to the Top 10%?

By combining Federal Reserve Distributional Financial Accounts with Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) and Brookings/Bricker et al. estimates, we can interpolate the position of the 90–99% wealth group. With ~36% of U.S. wealth and ~25–30% of that unrealized, the group adds another $12.5–15T in untaxed gains. Together with the top 1%, the Top 10% hold ~$32T, or ~80–85% of all unrealized gains.

Sources: Bricker et al. (Brookings, 2020), “Unrealized Capital Gains and the Measurement of Household Wealth”; Saez, Yagan, and Zucman (2021); Federal Reserve, Distributional Financial Accounts (DFA); Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF, 2019).

🔽 Click to Expand: Pinning down the Top 10%

- Wealth levels (Fed Distributional Financial Accounts):

- Top 1% ≈ 31% of wealth (~$43T).

- Next 9% (90–99%) ≈ 36% of wealth (~$50T).

- Unrealized shares (Brookings/Bricker et al. 2020, Saez-Yagan-Zucman):

- Top 1%: 41% of wealth unrealized.

- Next 9%: not directly published, but their portfolio mix (equities, pensions, housing) suggests ~25–30% of wealth unrealized.

- Result:

- Top 1% ≈ $17.6T unrealized.

- Next 9% ≈ $12.5–15T unrealized.

- Together = $30–33T unrealized gains.

That means the Top 10% hold ~80–85% of all U.S. unrealized gains, and a defensible working base is ~$32T.

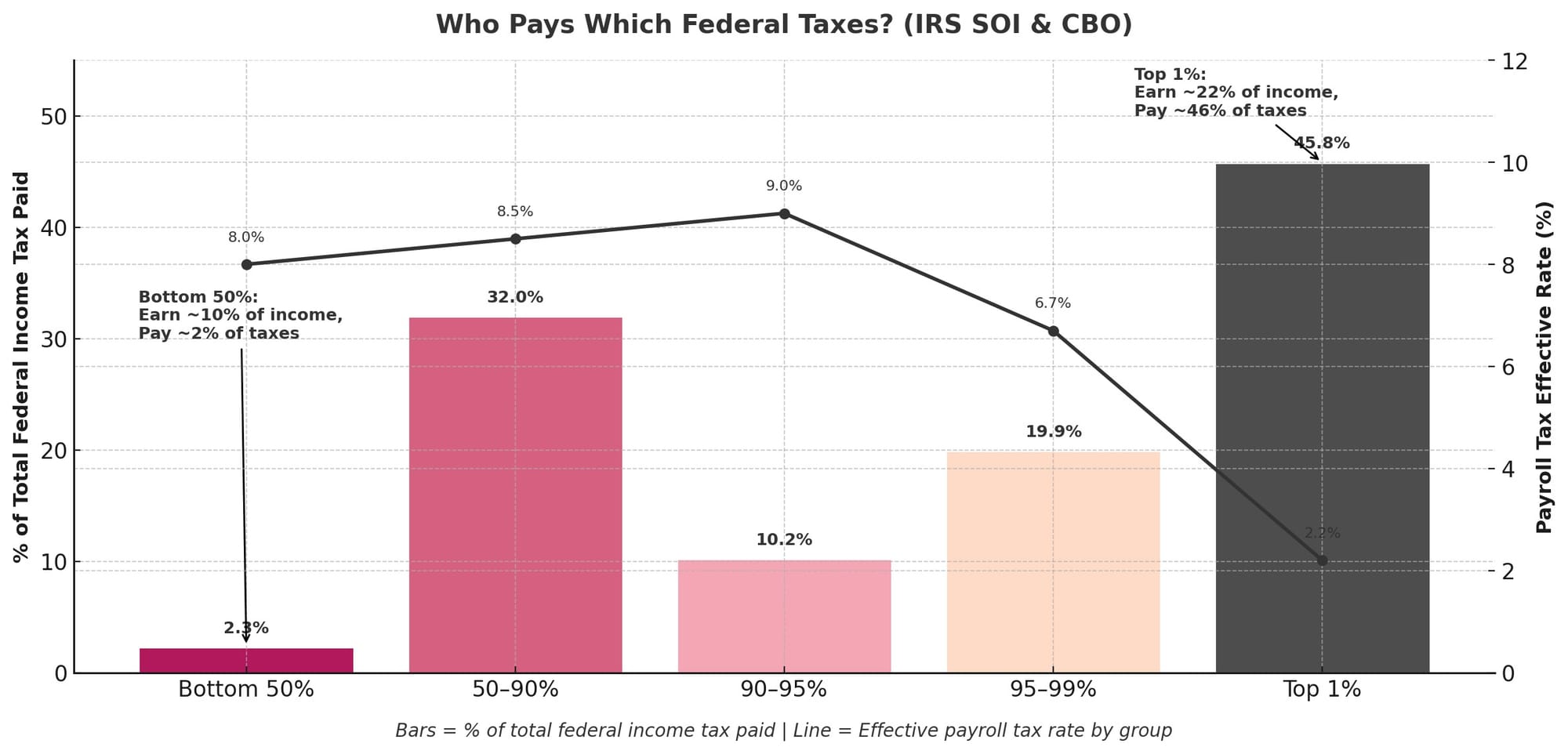

IRS statistics suggest the rich pay a lot—because they measure only realized income. In 2022:

- Bottom 50% earned ~10% of income, paid ~2–3% of income taxes.

- Top 1% earned ~22% of income, paid ~46% of income taxes.

But payroll taxes flip the story:

- Middle earners face ~8–9% effective payroll tax rates.

- The top 1% face ~2%, thanks to the Social Security cap.

Sources: Internal Revenue Service (IRS), SOI Tax Stats – Individual Income Tax Shares (2022); Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Distribution of Household Income and Federal Taxes (2022).

Debates over taxing unrealized gains are often cast in absolutes: some claim it could “solve the deficit,” others insist it is “unworkable.” The truth lies in between. The real question is: how much revenue could such a tax realistically generate, and how resilient would it be in downturns?

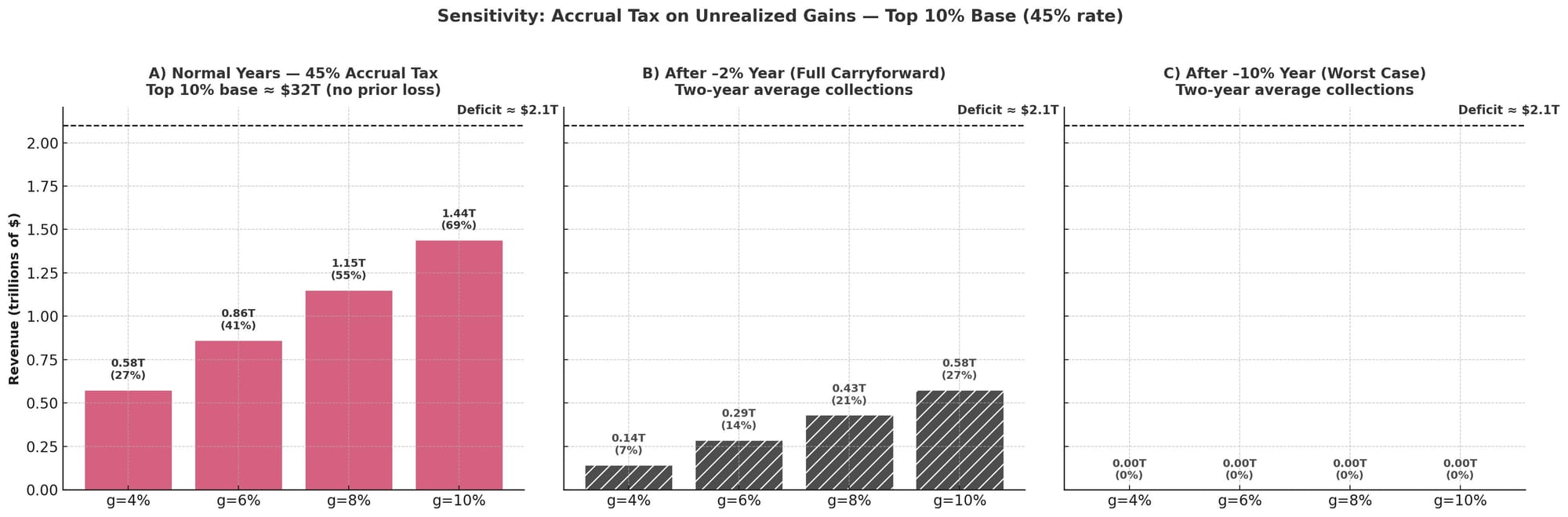

Because unrealized gains track asset values, revenues expand in good years but can collapse when markets fall. To probe both the magnitude and the volatility, we model a 45% accrual tax on the ~$32T of untaxed gains held by the Top 10% of households. We then test outcomes under different asset-growth paths, including downturns with loss carryforwards.

What the Numbers Reveal

- In strong years, the levy could raise $0.6T–$1.4T, covering up to 70% of the $2.1T deficit.

- After a mild –2% year, average revenues fall sharply, to just 7–27% of the deficit.

- After a severe –10% crash, revenues are effectively wiped out under full carryforward rules.

Sources: Calculations based on: Federal Reserve DFA (Q2 2023 net worth ≈ $139T); Bricker et al. (Brookings, 2020) unrealized-gain ratios; IRS tax rate assumptions.

Even in optimistic years, accrual taxation does not eliminate the deficit. At best, it plugs two-thirds of the gap; at worst, it collapses to zero. This highlights a more troubling reality: the U.S. fiscal imbalance is not simply a story of untaxed fortunes. It reflects:

- Structural expenditure growth — entitlements and interest rising faster than GDP.

- Revenue base erosion — payroll and corporate taxes lagging behind the modern economy.

- Volatility risk — overreliance on asset-linked taxation exposes the budget to market cycles.

In short, taxing unrealized gains could meaningfully narrow the gap, but the deficit is ultimately a systemic problem—not one that can be solved by any single tax lever.

At a time when authoritarian rivals are closing ranks, the U.S. cannot afford to weaken its alliances. The path to fiscal stability is not cutting NATO—it is closing the structural gap at home. And that means looking seriously at the untaxed trillions sitting in unrealized gains, rather than asking whether America can still afford to lead.

The West cannot afford to weaken its alliances while rivals outside the capitalist—or even social democratic—order close ranks; America must first repair its fiscal foundation.