Is Democracy in Decline? A Housekeeper’s Perspective on the World’s Democratic Crisis

Based on a real story

Irina moves quickly through the house, dusting, wiping, scrubbing. Her phone is tucked under her ear, and as she cleans, she listens intently. It’s her English lesson, one of the few things she does for herself in between running her cleaning business and caring for her family. Her teacher asks, “What do you think about the state of the world?”

She sighs. "I think people want dictators now," she says. "Maybe democracy is not working anymore."

I pause, startled. Irina is a Ukrainian immigrant in the United States, someone who has lived through the fall of the Soviet Union, the Orange Revolution, and the war that shattered her homeland. If anyone should believe in democracy, it’s her. But instead, she sees a world tilting toward autocracy.

A Global Shift Away from Democracy

Irina’s words stay with me. Is she right? Is democracy failing?

For 17 consecutive years, democracy has been in decline. Countries that were once considered strongholds of freedom—Hungary, Turkey, Brazil, India—have shifted toward autocracy. Even the United States, long viewed as a beacon of democracy, has seen its institutions tested by deep polarization and misinformation.

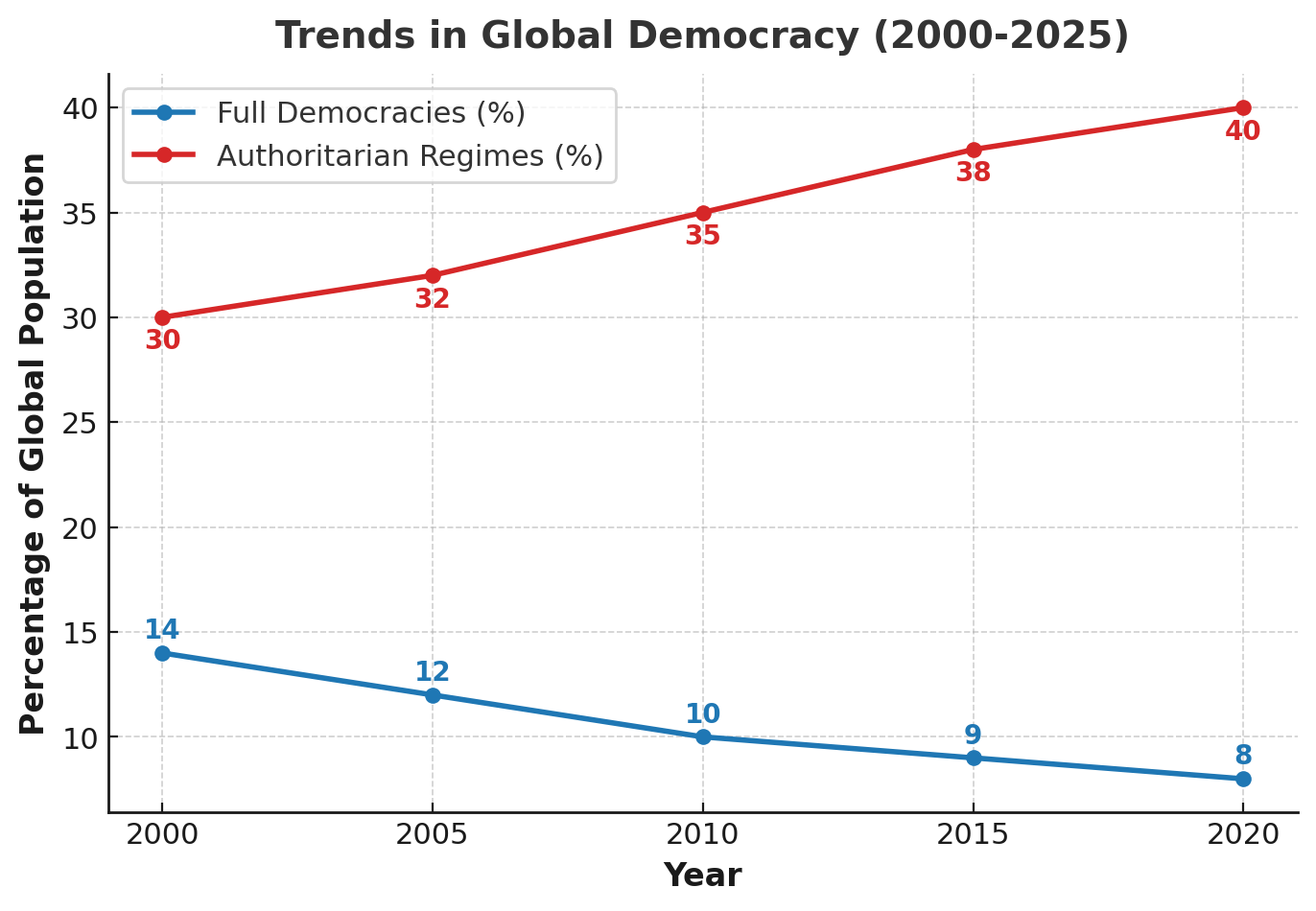

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, the percentage of the world’s population living under "full democracies" has shrunk to just 8%, while nearly 40% now live under authoritarian regimes. The balance is shifting, and not in democracy’s favor.

🔽 Click to Expand: Global Democracy Indices–What the Data Shows

2000 to 2025 Empirical Trends and Data

Global indicators suggest a broad decline in democratic governance from the early 2000s through 2025. After steady gains in the 1990s, many measures of democracy peaked in the mid-2000s and have since trended downward. Freedom House’s Freedom in the World reports show that global freedom has declined each year since 2005, marking a 17-year democratic recession as of 2022 gijn.org. In Freedom House’s inaugural 1973 survey, only 30% of countries were rated “Free,” rising to 46% by the early 2000s – but that progress stalled and reversed. By 2023, just 84 of 195 countries (43%) are classified as Free, and only 20% of the world’s population lives in these Free countries (the rest live in Partly Free or Not Free states) libertascouncil.org. In fact, 38% of people globally now reside in “Not Free” countries, reflecting how populous states like China (Not Free) and even India (rated Partly Free in recent years) tilt the population balance toward authoritarian rule v-dem.net.

Multiple research institutions corroborate these trends with quantitative data. The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project finds that for the first time since the 1990s there are more closed autocracies than liberal democracies worldwide v-dem.net. The number of liberal democracies fell from a peak of 44 countries in 2009 to just 32 in 2022 v-dem.net. Meanwhile, the share of the world’s population living in some form of autocracy surged to 72% (5.7 billion people) by 2022, up from 46% a decade earlier v-dem.net. At the country level, the world is now split roughly in half: about 90 states are electoral democracies (of varying quality) and 89 are autocracies v-dem.net. Many democracies that do exist are less liberal than before – V-Dem notes a decline in countries with strong institutional protections for freedoms, as liberal democracy gives way to more illiberal, weakly constrained forms of electoral rule.

Global democracy scores by country (The Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index 2022). Darker green indicates “full democracies,” yellows and light orange are flawed or hybrid regimes, and red tones are authoritarian regimes. Every region except Western Europe saw democratic backsliding in recent years. democracywithoutborders.org democracywithoutborders.org

Other indices echo this democratic backsliding. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index shows the global average democracy score fell from 5.52 in 2006 to an all-time low of about 5.17 by 2023 democracywithoutborders.org. In 2023, the EIU classified only 24 countries (under 8% of the world’s population) as “full democracies,” while 59 countries (over 39% of the population) lived under “authoritarian regimes”democracywithoutborders.org. The global average score in 2023 dropped to 5.23 (on a 0–10 scale) – the worst since the index began in 2006 – confirming “a general trend of regression and stagnation in recent years,” according to EIU’s analysts democracywithoutborders.org. Regional data highlight that democratic decline is most pronounced in regions like Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, and parts of Asia, while Western Europe has largely maintained high scores democracywithoutborders.org. For example, 2023 marked the eighth consecutive year of democratic decline in Latin America, with countries like El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras seeing especially sharp erosions of democratic norms democracywithoutborders.org. Central and Eastern Europe have also backslid due to the rise of illiberal leaders, and even the United States saw its score fall in recent years amid polarization and institutional stress. In the Middle East and North Africa, the hopes of the early 2010s Arab Spring have mostly collapsed (Tunisia, once a success story, slid back to autocracy by 2021), keeping that region’s democracy levels the lowest in the world democracywithoutborders.org.

Not all the news is bleak – a few bright spots persist. Freedom House’s 2023 report noted that the gap between the number of countries registering declines and those with improvements was the narrowest in 17 years (35 countries worsened, 34 improved), hinting at a possible turning point gijn.org. Some nations have bucked the trend: e.g. Colombia, Slovenia, and Kosovo made notable democratic improvements in 2022, and Zambia and Malawi saw peaceful transfers of power in recent elections gijn.org. Nonetheless, the overall picture since 2000 is one of democratic institutions under strain worldwide, with signs of a sustained “democratic recession” over the past 15+ years diamond-democracy.stanford.edu.

Why Are People Turning Away from Democracy?

Irina’s frustration isn’t unique. Around the world, people are growing disillusioned with democratic governance. In country after country, politicians once elected to protect democracy have instead used their power to dismantle it.

"People don’t care about democracy when they are struggling to survive," Irina tells me. And the data backs her up. Economic inequality has widened, and in many democracies, wages have stagnated while the cost of living soars. In places like Latin America, the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent economic stagnation have led many voters to embrace leaders who promise strong, decisive action—whether democratic or not.

Meanwhile, populist strongmen have risen by tapping into this anger. Leaders like Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey came to power through democratic elections, only to weaken institutions, suppress media freedoms, and tilt elections in their favor. The playbook is eerily similar across nations.

🔽 Click to Expand: Case Studies of Democratic Backsliding

Political and Institutional Drivers

Several political and institutional factors have driven this global democratic decline. A key element is the rise of populist movements and strongman leaders who challenge liberal democratic norms. Across many countries, anti-establishment populists gained support by tapping into public discontent and then used their mandates to weaken checks and balances. In Europe and the United States, for instance, illiberal populism has moved from the fringes to the halls of power. Diamond Democracy notes that the election of a U.S. president in 2016 who embraced populist rhetoric surprised many observers and highlighted the vulnerabilities of even the most stable democracies diamond-democracy.stanford.edu.

In Central Europe, leaders like Viktor Orbán in Hungary and the Law and Justice (PiS) party in Poland rose on populist, nationalist rhetoric and proceeded to erode judicial independence, monopolize media, and undermine pluralism diamond-democracy.stanford.edu diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Orbán even proclaimed Hungary an “illiberal democracy,” and many analysts argue Hungary is no longer a true democracy after more than a decade of such changes diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Poland’s government similarly has weakened institutional checks, prompting EU sanctions over rule-of-law breaches diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Populist leaders in the Philippines (Rodrigo Duterte), Brazil (Jair Bolsonaro), Turkey (Recep Tayyip Erdoğan), and elsewhere followed a comparable script: channel popular frustration with “elites” or societal problems into electoral victory, then concentrate power by undermining courts, legislatures, the press, and civil society.

Executive overreach and the erosion of accountable governance have thus become common features of democratic backsliding. Once in office, populist or opportunistic leaders often rewrite rules to entrench themselves. Examples abound: Turkey’s Erdoğan used constitutional changes and emergency decrees (especially after a 2016 coup attempt) to squeeze the opposition and extend his rule well beyond normal term limits. Russia’s Vladimir Putin, though coming to power in a fledgling democracy around 2000, steadily dismantled that democracy through centralizing authority, scrapping gubernatorial elections, jailing opponents, and recently amending the constitution to potentially stay in power until 2036 – turning Russia into a full autocracy diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Even in smaller or newer democracies, leaders have pushed the boundaries – from Bangladesh to Tanzania, incumbent governments have harassed opponents and tilted the playing field to remain in chargediamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Democratic institutions like independent judiciaries, free electoral commissions, and robust legislatures have been weakened or co-opted in many countries, allowing executives to act with fewer constraints. This executive aggrandizement hollows out the liberal aspect of democracy (rights and checks) even where elections still occur.

Another driver is the manipulation of electoral processes and norms, both by domestic actors and foreign interference. In some cases, democratically elected governments have changed election rules to entrench advantages – such as gerrymandering districts, raising barriers for opposition parties, or capturing election oversight bodies. Elsewhere, incumbents resort to outright repression around elections: jailing challengers, banning protest, or flooding the media with propaganda. Competitive authoritarian regimes – states that hold elections but under profoundly unfair conditions – have proliferated. Countries like Venezuela under Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro, Nicaragua under Daniel Ortega, or Cambodia under Hun Sen saw elections become window dressing as the regime strangled true competition diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Even some elected leaders in Africa (Uganda’s Museveni, Zimbabwe’s former leader Mugabe) clung to power through dubious elections. Furthermore, foreign meddling has challenged electoral integrity in open societies. A stark example was Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. elections via hacking and online disinformation; intelligence reports found that Russian cyber campaigns sought to “amplify mistrust in the electoral process” and swing voter perceptions brookings.edu. Similar interference by Moscow was reported in European elections (France, Germany) and referendums (the Brexit campaign saw alleged Russian disinformation). These attacks on election integrity – whether through misinformation, hacking, or illicit funding – undermine public confidence in democracy and, in some cases, may alter outcomes.

Compounding these issues is declining trust in democratic institutions and a crisis of democratic legitimacy. In many established democracies, citizens have grown increasingly distrustful of parliaments, parties, the media, and even the electoral process itself. Global surveys show a steep drop in institutional trust over the past two decades. One comprehensive study found that by 2019, 57.5% of people worldwide were dissatisfied with “the way democracy is working”, up from 47.9% in the mid-1990s cam.ac.ukcam.ac.uk. This marks the highest level of democratic discontent on record, with especially sharp spikes in dissatisfaction since around 2005 cam.ac.uk. Major democracies including the United States, United Kingdom, Brazil, Mexico, and Australia have hit all-time highs in public dissatisfaction with their democratic system cam.ac.uk.

Eroding trust in institutions creates a vicious cycle: when people believe governments and courts don’t serve them, they become more willing to support outsiders or even anti-democratic alternatives, which in turn further weakens those institutions. For example, surveys in the U.S. reveal faith in Congress has sunk to single digits, and only about 20% of Americans say they trust the federal government “most of the time” diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Such skepticism has fueled anti-establishment movements and weakened the norms of mutual tolerance and forbearance that democracies rely on. In young democracies, institutional trust tends to be even more fragile – and once broken, can open the door to military coups or authoritarian strongmen promising order. Overall, low public confidence in democratic governance has both resulted from and contributed to democratic backsliding around the world.

The Economic Divide and Democracy’s Erosion

Irina stands by the window, folding a cloth over her hands. "You know, back home, we used to believe that working hard meant you’d get ahead," she says. "But now? The rich get richer, and the rest of us just struggle."

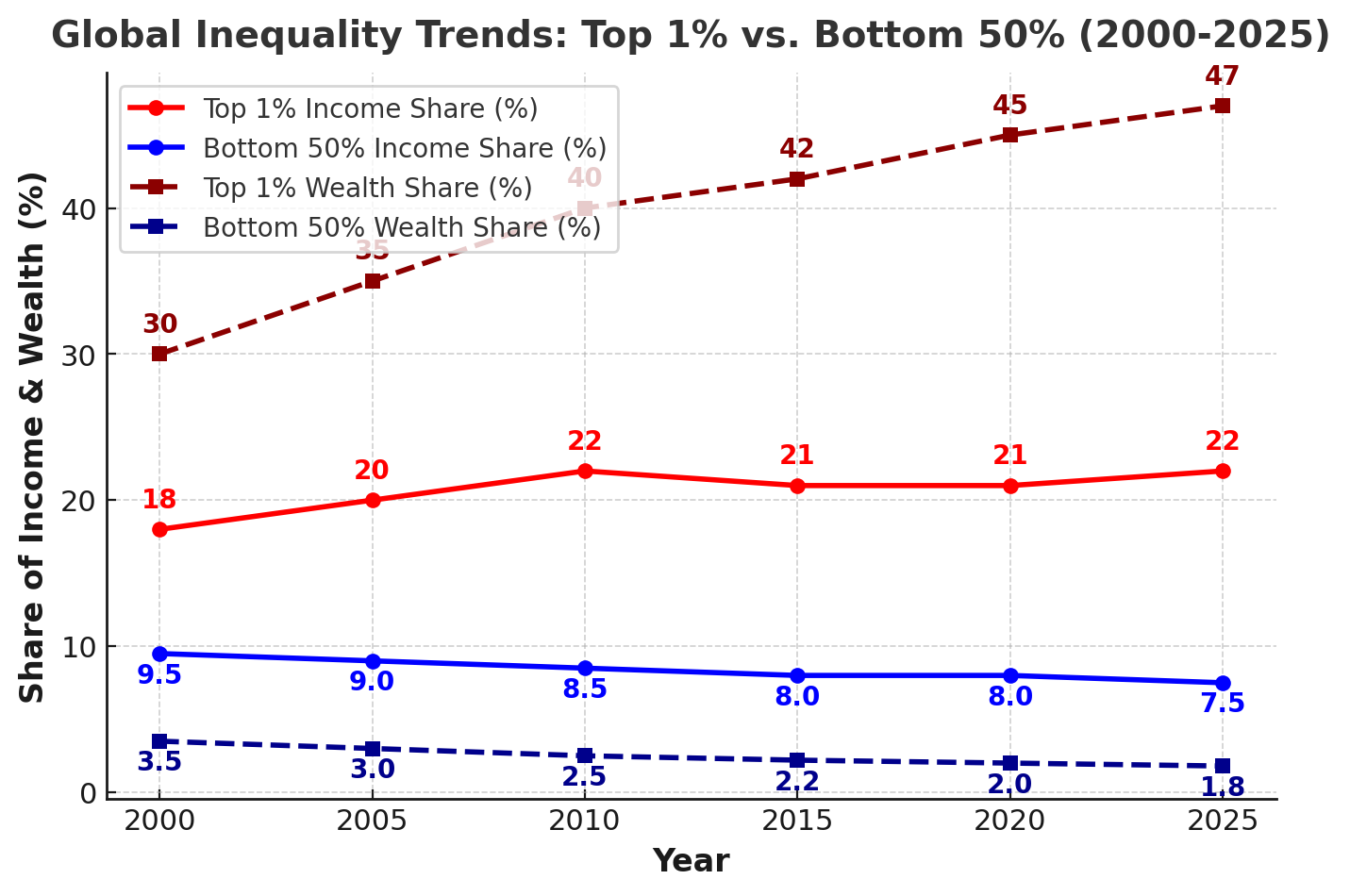

She isn’t alone in this belief. Across the world, the gap between the wealthiest and the rest has widened drastically. The top 1% now controls nearly 40-45% of the world's wealth, while the bottom 50% owns just 2%. For many, democracy feels like an illusion when economic power is so concentrated at the top.

🔽 Click to Expand: The Growing Gap Between the Rich and Poor

Global Income and Wealth Inequality: Trends and Impacts Top 1% vs Bottom 50%: Income and Wealth Shares

Global inequality is stark. Recent data show that the richest 10% of the world’s population capture 52% of global income, whereas the poorest 50% receive only about 8% wir2022.wid.world. On average, an individual in the top tenth earns over 30 times more than someone in the bottom half. Wealth disparities are even greater: the top 10% own about 76% of global wealth, while the bottom half owns just 2% wir2022.wid.world. This means billions of people split a tiny fraction of global assets, whereas a small elite holds the vast majority. In fact, estimates indicate the top 1% alone now hold roughly 40–45% of the world’s wealth advisors.ubs.com – nearly as much as the remaining 99% combined. The flipside is that the poorer half of the global population has virtually no wealth and very low income shares, underscoring a massive gap in economic resources.

Rising Inequality Trends Since 1980

Inequality has worsened over the past few decades in many regions. According to comprehensive studies by economist Thomas Piketty and colleagues, the global top 1% income share rose from around 16% in 1980 to about 22% by 2000, and remains about 20% today wir2018.wid.world. In contrast, the global bottom 50% has persistently received only around 9% of income wir2018.wid.world. In other words, the top 1% (tens of millions of people worldwide) earn about twice as much combined income as the poorest 50% of humanity wid.world. Over 1980–2016, the top 1% captured 27% of total income growth – twice as much as the bottom 50% gained wid.world. This divergence is mirrored within many countries. For example, in the United States (a high-inequality country), the richest 1% received about 10% of national income in 1980; by 2016 their share had doubled to roughly 20%, while the bottom 50%’s share fell from 20% to 13% mlkglobal.org. Western Europe, with stronger redistributive policies, saw a milder increase (top 1% rising from ~10% to 12%) mlkglobal.org.

In the United States, the share of national income going to the top 1% has roughly doubled since 1980, while the bottom 50%’s share has declinedn mlkglobal.org. This exemplifies the sharp rise in inequality in several countries, a trend also observed globally.

Not all countries have shared the same fate – some emerging economies reduced extreme poverty – but nearly all have seen the income gap widen to some extent since the 1980s mlkglobal.org. Piketty’s historical analysis shows that the mid-20th century had relatively lower inequality (thanks to progressive policies and shocks like world wars), but since 1980 we have effectively “reversed” the postwar egalitarian trendmlkglobal.org. By 2020, global inequality returned to a very high level, comparable to that of the early 20th century in terms of the concentration of income and wealth wir2022.wid.world wir2022.wid.world. In short, the past few decades have seen the top 1% pull far ahead, while the economic position of lower-income groups improved only marginally. Wealth inequality has followed a similar trajectory: for instance, in the U.S., the top 1% owned about 25–30% of wealth in the 1980s, but around 40% by 2016ideas.repec.org. This rise of private fortunes and stagnation of broad-based prosperity has prompted growing concern among economists and policymakers.

Consequences for Economic Stability and Democracy

Rising inequality can carry serious economic and political consequences. The International Monetary Fund warns that very high inequality can undermine sustainable growth and destabilize societies. When a society’s riches concentrate at the top, it often “concentrate[s] political and decision making power in the hands of a few,” leading to suboptimal investment in human capital and even greater instability imf.org. IMF research finds that if the income share of the rich increases, overall GDP growth tends to decline over the medium term, whereas boosting the share of the poor and middle class supports stronger growth imf.orgimf.org.

Extreme inequality can erode social cohesion and fuel grievances. Studies have linked the rise of top incomes to financial crises – for example, stagnant incomes for the poor and middle while the wealthy gained influence contributed to excessive debt and risk-taking prior to the 2008 crisis imf.org imf.org. In unequal societies, elites may use their wealth to shape policies in their favor (through lobbying or other means), potentially entrenching a feedback loop of inequality and weaker governance imf.org.

Democracy can also be threatened by unchecked inequality. Piketty and other scholars caution that when wealth becomes highly concentrated, it endangers the principle of equal representation. Piketty’s landmark work highlights a “central contradiction” of capitalism: if the return on capital remains higher than the economy’s growth rate for long periods, inherited wealth will grow faster than earned income, causing ever-increasing inequality britannica.com. He warns that such inequality could reach “unsustainable levels…that could threaten democracy” britannica.com.

In a scenario of extreme concentration (what he calls “patrimonial capitalism”), political power may increasingly reflect wealth rather than the will of the majority. This danger isn’t just theoretical: history shows that oligarchic societies often suffer from social unrest or hollowed-out democratic institutions. Modern signs include rising populism and distrust in institutions, which many observers tie partly to feelings of injustice in highly unequal economies.

Conclusion

In summary, credible data from the World Bank, IMF, OECD, and academic research paint a consistent picture of high and in many cases rising global inequality. A tiny elite commands a hugely disproportionate share of income and wealth, a gap that has widened since the 1980s in much of the world. These trends raise red flags for economic stability and the health of democracies. As Piketty’s analysis and international organizations suggest, addressing inequality is not merely a matter of social fairness but also crucial for sustaining growth and inclusive governance. Policymakers are increasingly urged to respond – through progressive taxation, investment in education and health, and other inclusive policies – to ensure that economic prosperity is broadly shared and that democracy remains robust in the face of concentrated wealth.

Sources: World Inequality Lab (WID) wir2022.wid.worldwir2022.wid.world wir2018.wid.world wid.worldwid.world; IMF and World Bank analyses imf.orgimf.org imf.org; Thomas Piketty’s findingsbritannica.commlkglobal.org.

The Role of Technology and Misinformation

Irina puts her phone down for a moment and shakes her head. "I don’t know what to believe anymore," she says. "Everything online is a lie."

She’s not wrong. Social media, once celebrated for its role in spreading democratic ideals, has instead fueled misinformation and polarization. Fake news spreads faster than real news. Authoritarian regimes have mastered digital surveillance and propaganda, making it easier to manipulate public opinion and silence dissent. In some cases, online disinformation campaigns have even swayed elections and deepened divisions within democratic societies.

🔽 Click to Expand: The Role of Economic Inequality and Social Media in Democracy’s Decline

Economic and Social Factors

Beyond politics, economic and social currents since 2000 have undercut democracy’s appeal and stability. Foremost is the impact of economic inequality and insecurity. In many countries, the benefits of globalization and growth have been unevenly distributed, leading to a sense that democracy has failed to deliver fairness. The late 20th-century neoliberal era saw rising GDP but also surging income inequality in both developed and emerging economies. By the 2010s, a wealthy urban elite prospered while many middle- and working-class communities faced stagnating wages, job losses from offshoring or automation, and eroding social safety nets. This economic resentment created fertile ground for populist politicians, who railed against “corrupt elites” and promised to restore dignity to the “left-behind” people. As scholar Larry Diamond notes, the 2008 global financial crisis was a pivotal moment: it had “longer-lingering effects” than anticipated, squeezing real incomes and fueling anger among working and middle classes in the U.S. and Europe diamond-democracy.stanford.edu.

The crisis and subsequent Eurozone debt woes hit younger democracies in Southern Europe especially hard (e.g. Greece, Spain), sparking mass protests and the rise of anti-establishment parties. In many Western democracies, economic pain translated into political upheaval – voters increasingly embraced candidates on the far-left or far-right who pledged to break the status quo. Diamond observes that post-2008 economic stress “made significant segments of the electorate more susceptible to the appeals of nativist, populist, and illiberal alternatives” diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Indeed, phenomena like the Brexit vote in the UK and the gilets jaunes protests in France were tied to grievances about globalization’s winners and losers. In developing nations as well, high inequality correlates with weaker democratic norms, as oligarchic economic control often subverts equal political participation, and poor majorities grow disillusioned with democracy’s ability to improve their lot.

Social dynamics have also played a role, particularly the rapid spread of social media and online misinformation. The rise of Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms in the 2000s fundamentally changed information ecosystems. While these platforms have empowered citizen voices and mobilized pro-democracy activism at times (for example, during the Arab Spring uprisings or various protest movements), they have also severely undermined the quality of public discourse. False or misleading information can now circulate to millions at lightning speed, often with minimal fact-checking. Authoritarian actors and domestic demagogues alike have exploited this: flooding social media with propaganda, conspiracy theories, and troll-driven harassment of independent journalists or opposition figures. The result is a more polarized, paranoia-prone public.

Experts warn that social networks have “hijacked democracy” by rewarding outrage and rumor over reasoned debate pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. For instance, in the United States, the proliferation of election conspiracies and “fake news” on social media contributed to a segment of the population believing the 2020 presidential vote was fraudulent – a falsehood that culminated in the January 6, 2021 Capitol riot. As one analysis notes, “the explosion of misinformation deliberately aimed at disrupting the democratic process…confuses and overwhelms voters” brookings.edu. This pattern is global: from India to Brazil to Europe, online misinformation and hate speech have inflamed division and distrust, sometimes even inciting violence. Social media algorithms, optimized for engagement, often create echo chambers that exacerbate partisan divides, making democratic compromise harder. In summary, while the internet opened new avenues for participation, its dark side in the form of unchecked misinformation and extremist content has posed a serious challenge to democratic norms and informed citizen decision-making diamond-democracy.stanford.edu.

Other social factors have interacted with these trends. Demographic and cultural changes – such as increased immigration or shifting racial/religious compositions – have at times provoked backlash in democracies. Large-scale migration and the perceived loss of traditional identity have been skillfully leveraged by illiberal politicians. For example, the influx of refugees and migrants into Europe in the mid-2010s (fleeing conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and elsewhere) triggered a nativist reaction. Diamond observes that “increasing globalization – movements across borders of people – added to the anxiety of many voters”, who felt national sovereignty was under threat diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. This anxiety benefited far-right parties that promised to fortify borders and preserve national identity, often at the expense of minority rights or international norms. In the U.S., similarly, rising immigration levels (approaching historic highs as a percentage of population) corresponded with growing support for anti-immigrant, nationalist rhetoric in politics diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Thus, social cleavages around identity and immigration have strained democratic pluralism, as some citizens become receptive to exclusionary, authoritarian solutions to these perceived societal threats.

Finally, unforeseen crises like the COVID-19 pandemic have had mixed effects on democracies. On one hand, many democratically elected governments invoked emergency powers, imposed lockdowns, and expanded state surveillance to manage the public health crisis, which raised concerns about executive overreach. Freedom House documented that pandemic measures in 2020–21 often curtailed freedoms of assembly and expression (such as bans on protests or censorship of “misinformation”), contributing to freedom score declines in a number of countries gijn.org. Authoritarians seized the moment too – for instance, Hungary’s government ruled by decree for months, and China used stringent lockdowns with high-tech monitoring. On the other hand, these restrictions were largely temporary in open societies, and by 2022 many democracies rolled back COVID-related limits gijn.org. In some regions, the restoration of civil liberties post-pandemic even produced a small rebound in democratic indicators gijn.org. The pandemic also highlighted the importance of competent governance – some democracies (e.g. New Zealand, Taiwan) handled it effectively, potentially bolstering trust, whereas others floundered. Overall, the economic fallout from COVID-19 (recession, inequality) and the social frustrations of lockdowns added another layer of stress on democracies, but the long-term impact on global democratic trajectories is still unfolding.

The Geopolitical Battle Between Democracy and Autocracy

While Irina works, I continue my research. She talks about Ukraine, about Russia, about how people in her home country once believed the West would always be their ally. But the world is shifting.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, democracy had the upper hand. But today, authoritarian powers like China and Russia are reshaping the global order. China’s state-controlled capitalism is proving that economic growth doesn’t require democracy, while Russia actively works to undermine democratic elections abroad. Countries in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, once pressured to adopt democratic reforms, now find themselves courted by these alternative models.

"People want stability more than freedom," Irina says. "And dictators promise stability."

🔽 Click to Expand: How China and Russia are Reshaping Global Democracy

Geopolitical and External Pressures

Domestic factors alone do not explain democracy’s global decline; geopolitical forces and external pressures have also been influential. In the 1990s, the international environment was largely favorable to democratization – the United States and European Union actively promoted democratic governance, and there was no serious geopolitical rival to the liberal democratic model. By the 2010s, that had changed dramatically. Authoritarian powers like China and Russia have grown in relative power and ambition, and they openly challenge the democratic world order. Beijing and Moscow present themselves as alternatives to liberal democracy, touting a model of centralized authority and state-directed development. According to analysts, these regimes propagate a narrative that “democracy is passé, leading to chaos and stagnation, and that concentrated power is the path to progress” diamond-democracy.stanford.edu.

This messaging, pushed through state-sponsored media and diplomatic channels, seeks to legitimize authoritarian governance worldwide. Autocrats in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East increasingly identify with China and Russia as role models, pointing to their rapid economic gains or military assertiveness as proof that liberal norms are not requisite for success diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. For example, leaders in countries from Cambodia to Uganda have strengthened ties with China, benefiting from Chinese investments and technology without pressure to reform politically. This “authoritarian solidarity” has created a more permissive international climate for autocracy to spread diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Whereas in previous decades a coup or power grab might be met with broad Western condemnation and sanctions, today there are powerful patrons willing to shield or reward authoritarian behavior.

Another geopolitical factor is the impact of conflicts and security crises, which can undermine democracies. The U.S.-led “War on Terror” after 9/11, for instance, had a paradoxical effect: while intended to secure democracy against terrorism, it also gave many governments cover to adopt draconian measures. Under the banner of counterterrorism, democratic states from the U.S. to India to France expanded surveillance, curtailed due process for suspects, and passed sweeping security laws.

Authoritarian regimes eagerly copied this playbook; e.g. Russia justified brutal crackdowns in Chechnya and later against domestic dissent as anti-terror operations, and China labeled Muslim Uyghurs as a terrorist threat to justify mass detention and Orwellian surveillance in Xinjiang. These moves erode democratic freedoms and normalize authoritarian tactics.

Active wars and coups themselves also set back democracy: the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, while removing a dictator, led to years of chaos and sectarian violence that have hindered democratic development in the region. The Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 brought hope to the Middle East, but subsequent civil wars in Libya, Yemen, Syria and the return of military rule in Egypt dashed those hopes. Ongoing conflicts – such as the devastating civil war in Syria or Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine – have polarized the international arena and sometimes prompted democratic countries to compromise on values (e.g. overlooking human rights abuses by allies in the name of security). Moreover, war itself can directly extinguish democracy: Myanmar’s fragile democracy was snuffed out by a military coup in 2021, and Mali’s and Burkina Faso’s elected governments were overthrown by juntas amid jihadist insurgencies. According to V-Dem, nine countries (including Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Mali) descended from democracy into outright closed autocracy just in the last few years, largely due to coups or conflict-related breakdowns v-dem.net.

Foreign intervention and election meddling have further tilted the playing field. We noted Russia’s role in spreading disinformation abroad; beyond that, Moscow has provided material support to like-minded illiberal forces (for example, funding far-right parties in Europe, or assisting dictators like Bashar al-Assad in Syria). China, for its part, wields influence primarily through economic means – its massive Belt and Road Initiative investments often flow to authoritarian-leaning states in Asia and Africa, bolstering their economies (and the regime’s stability) without demands for democratic reform. Beijing also exports sophisticated surveillance technologies to any interested government, facilitating what some call “digital authoritarianism” ictworks.org. From facial recognition cameras to internet firewalls, Chinese tech is enabling other regimes to monitor and control citizens in ways previously seen only in China.

The spread of these tools makes it easier for autocrats to prevent the organization of opposition and stifle free expression, thereby weakening prospects for democratic change. Additionally, the retreat of Western democracy promotion has had consequences. Western democracies have become more hesitant and inward-focused in defending democracy abroad, especially after failures like Iraq. Diamond notes that the “debacle” of the Iraq War “gave democracy promotion a bad name” and led the U.S. to “downgrade democracy promotion” in its foreign policydiamond-democracy.stanford.edu.

In the 1980s-2000s, robust engagement by the U.S. and EU (through diplomacy, aid conditionality, support for civil society) often helped nascent democracies survive challenges diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. But in the 2010s, as populism and polarization rose at home, the West’s attention to fostering democracy elsewhere waned. This created a vacuum that authoritarian powers have been happy to fill, and it emboldened autocrats who no longer fear strong international censure. Multilateral institutions have also been stymied: organizations like the U.N. Human Rights Council saw increased influence of non-democracies (e.g. China and Russia using their seats to deflect criticism of human rights abuses), and attempts to coordinate global responses to democratic backsliding (such as sanctions on regimes like Venezuela or Myanmar) often face vetoes or lack of consensus.

In summary, the geopolitical context since 2000 shifted from a unipolar pro-democracy climate to a more contested environment. Democratic ideals now compete with a resurgent authoritarian narrative on the world stage. Global power struggles – including a potential new Cold War between the U.S. and China/Russia – have sometimes sidelined democracy promotion in favor of realpolitik. These external pressures make it harder for struggling democracies to consolidate and easier for autocrats to tighten their grip, contributing significantly to the worldwide democratic decline.

Is There Hope for Democracy’s Future?

Before she leaves, I ask Irina, "Do you really believe democracy is dying?"

She hesitates. "I don’t know. Maybe. But I also know that when you are free, you think about everything—politics, justice, what is right. When life is hard, all you think about is tomorrow."

Her words linger. Democracy is struggling, but history has shown that it moves in waves. There have been periods of democratic decline before—during the rise of fascism in the 1930s, during the Cold War. Each time, democracy fought back. Some countries today, like Colombia and Slovakia, have rejected autocracy and embraced democratic renewal.

The real question is: Can democracy adapt? If democratic societies fail to address inequality, corruption, and institutional distrust, the trend will continue downward. But if they find ways to strengthen their institutions and rebuild public trust, a new wave of democratization may still be on the horizon.

"Maybe if people felt safe, they wouldn’t need strongmen," Irina says before walking out the door.

Maybe she’s right.

For now, the battle between democracy and autocracy is far from settled. The next decade will be decisive in determining which system prevails.

🔽 Click to Expand: Historical Cycles and Future Outlook

Historical Cycles and Future Outlook

The current downturn raises the question: is this a temporary setback in democracy’s expansion, or a more fundamental transformation of the global system? History suggests that democratization has never been a linear march upward, but rather has occurred in waves with periods of reversal.

Political scientist Samuel Huntington famously described three waves of democratization: a long first wave in the 19th century ending with a reverse wave in the 1930s (when many democracies fell to fascism or dictatorship), a second wave after WWII that receded during the Cold War, and a third wave from the 1970s through the 1990s that ushered in dozens of new democracies. By the early 2000s, some speculated a fourth wave might be underway, but instead we appear to have entered a “third reverse wave” or global democratic recession. Around 2006–2007, observers noted that the post–Cold War democratic expansion had stalled, and Freedom House began recording more countries declining in freedom each year than gaining diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Over the last 15+ years, the rate of democratic breakdown (countries ceasing to be democracies) climbed back up to levels last seen in the 1970s diamond-democracy.stanford.edu. Thus, in historical perspective, democracy is undergoing a correction of its overextension into environments where it hadn’t taken deep root, as well as facing new challenges in even the heartlands of liberal democracy.

However, it is important to recognize that democracy’s overall global presence remains near historic highs by some measures. Today roughly half of all countries are electoral democracies – far more than in the 1970s, when only about 1 in 5 countries were democratic ourworldindata.orgourworldindata.org. The current decline has been real but relatively modest in terms of the number of democracies: what has changed more dramatically is the quality of democracy and the fact that some large pivotal countries (e.g. Russia, Turkey, Venezuela, and more recently India) have shifted toward authoritarianism. This means that while democracy as a form of government is down, it is not out. Many nations have retained at least the shell of democratic institutions, and public aspirations for democracy have not evaporated.

In fact, global surveys indicate that ordinary people across the world still broadly desire democratic rights and self-government. As one analysis put it, “democracy may be receding somewhat in practice, but it is still globally ascendant in people’s values and aspirations” journalofdemocracy.org. For example, Pew Global Attitudes surveys often find majorities in many countries (including non-democracies) say that a democratic system is a good way of governing their country – even if they are frustrated with the current functioning of democracy.

Looking to the future, experts are divided on whether we are experiencing a transient downturn or a long-term paradigm shift. On one hand, there are signs that this democratic recession could eventually bottom out and give way to a revival. The turbulence of the 2010s has spurred pro-democracy activism in many places: mass protests have challenged authoritarian moves in countries as diverse as Belarus (2020), Sudan (2019), Hong Kong (2019), and Venezuela (2019). While not all succeeded, they demonstrate resilience and popular demand for democracy. Some backsliding countries have also seen course corrections via elections or leadership change – e.g. Slovenia and Slovakia recently ousted illiberal governments at the ballot box, and in 2023 Turkey’s opposition mounted its strongest challenge to Erdoğan in years.

The narrow improvement in Freedom House’s 2022 report (with nearly equal numbers of countries improving as declining) hints that the post-2005 downward spiral might be slowing gijn.org. Additionally, democratic cooperation has revived somewhat in response to aggression by authoritarian powers – for instance, Russia’s war in Ukraine has unified the U.S. and European democracies in support of Ukraine, reinvigorating NATO and prompting Finland and Sweden to join that democratic security alliance. This kind of solidarity and reassertion of values could strengthen democracies going forward. Technological and social innovations may also bolster democracy: the same digital tools that enable disinformation can be harnessed for civic education and engagement, and there is growing awareness of the need to regulate social media to protect the information space.

In sum, optimists argue that democracy is adaptable and that current challenges will spur reforms – from improving social welfare to rein in inequality, to updating democratic institutions (e.g. experimenting with citizens’ assemblies or other participatory mechanisms) to rebuild public trust.

On the other hand, some fear that the current decline reflects deeper structural shifts that could herald a lasting transformation away from liberal democracy. The rise of China as an economic powerhouse presents a potent alternative model – authoritarian capitalism – that many leaders find attractive, especially in the developing world. Unlike the Soviet Union’s ideology, today’s Chinese model doesn’t seek to make the whole world communist, but its success undermines the assumption that economic development eventually necessitates democratization. If authoritarian regimes can deliver growth and stability, while some democracies flounder with polarization and inequality, the appeal of democracy may further diminish.

Moreover, emerging technologies like artificial intelligence-enabled surveillance could entrench authoritarian control in unprecedented ways, making it difficult for dissidents to organize and easier for regimes to manipulate public opinion. There is also a danger of democratic norms decaying from within. In established democracies, norms of mutual toleration and restraint have been eroding (witness the hyper-partisanship in the U.S. Congress or the frequent use of democratic institutions to punish opponents in countries like Poland). If domestic factions continue to treat politics as zero-sum warfare, democracies could degrade into dysfunctional, illiberal states or even break apart. Another concern is the global context of high-stakes crises – climate change, pandemics, and security threats might tempt societies to favor “efficient” authoritarian responses over the messiness of democracy. For instance, some argue that swift autocratic decision-making is better equipped to handle emergencies, which could sway opinions if democracies don’t rise to the occasion.

Most likely, the trajectory of global democracy will not be uniform. Different regions may diverge: we might see pockets of democratic renewal (for example, in some Asian or African countries where young populations push for change, or in Latin America if new leaders address corruption), even as entrenched autocracies persist elsewhere. International pressure and support will continue to matter – a concerted effort by democratic nations to prioritize democracy (through things like election monitoring, sanctions for coups, support for independent media abroad) could help tip the balance. Conversely, if the great power rivalry intensifies, authoritarian leaders may double down, anticipating little unified pushback.

In conclusion, evidence from 2000–2025 indicates that democracy has indeed been in a period of global decline, manifested in weaker institutions, more autocratic governments, and eroding public faith. The drivers are multifaceted – from populist politics and institutional failures to socioeconomic upheavals and geopolitical headwinds. History reminds us that such periods of decline are not unprecedented, and not irreversible. Whether this “democratic recession” marks a temporary setback or a more fundamental shift will depend on how democracies respond to their current challenges. If they can renew themselves – by reducing inequalities, restoring trust, regulating the digital sphere, and uniting to counter authoritarian influence – the global democratic wave may rise again. If not, the world could be entering an era in which liberal democracy is no longer the dominant governing paradigm.

The coming years will be crucial in determining democracy’s future trajectory, but the enduring desire of people for freedom and accountable government suggests that, even if diminished, democracy is far from defeated.

Key Takeaways 🗝️

- 🌍 Democracy in Retreat: Global democratic freedom has declined for 17 years, with only 8% of the world’s population living in full democracies, while nearly 40% live under authoritarian regimes.

- 📉 Populist Strongmen on the Rise: Leaders in Hungary, Turkey, and Brazil have weakened democratic institutions under the guise of reform.

- 💰 Economic Inequality & Disillusionment: Wages have stagnated, inequality has deepened, and many people prioritize stability over democratic principles.

- 📱 The Role of Social Media: Misinformation and digital surveillance are fueling polarization and weakening trust in democracy.

- 🇨🇳 Authoritarian Influence: China and Russia are reshaping global governance, offering alternative models to democratic institutions.

- 🔄 History Suggests Cycles: Democracy has declined before and rebounded—can it adapt and recover again?

Visual Insights 📊

The graphs below illustrate key economic and political trends shaping the decline of democracy.

📊 Graph 1: Global Democracy Trends (2000-2025) – Shows how full democracies have declined while authoritarian regimes have risen worldwide.

📊 Graph 2: Global Inequality Trends (2000-2025) – Illustrates the widening income and wealth gap between the top 1% and the bottom 50%, emphasizing the economic dimension of democracy’s decline.

Sources:

- Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2005–2023 reports (global freedom scores and country status trends) gijn.orggijn.org.

- Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, Democracy Report 2023 (data on regime types and population under autocracy) v-dem.netv-dem.net.

- Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2006–2023 (global and regional index scores) democracywithoutborders.org democracywithoutborders.org.

- Larry Diamond, “When Does Populism Become a Threat to Democracy?” (Stanford University talk, 2017) – analysis of democratic recession and populist/authoritarian trends diamond-democracy.stanford.edu diamond-democracy.stanford.edu diamond-democracy.stanford.edu diamond-democracy.stanford.edu.

- Roberto Foa et al., University of Cambridge Global Satisfaction with Democracy 2020 (survey of democratic discontent reaching record highs) cam.ac.ukcam.ac.uk.

- Pew Research Center & Edelman Trust Barometer (2010s–2023 global surveys on institutional trust and democratic attitudes) cam.ac.ukweforum.org.

- Brookings Institution, “Misinformation is eroding the public’s confidence in democracy” (2022) – on the impact of social media and foreign interference on U.S. democracy brookings.edu.

- Democracy Without Borders, “EIU 2023 Democracy Report: Regression in an Age of Conflict” (Feb. 2024) – summary of EIU findings and discussion of conflict and democracy democracywithoutborders.org democracywithoutborders.org.

- Freedom House, “Global Freedom Declines for 17th Consecutive Year” (press release, Feb. 2023) gijn.orggijn.org.

- Our World in Data, “Share of democracies has recently stagnated” (2024) – data showing long-term trends in democratic prevalence ourworldindata.orgourworldindata.org.

- World Inequality Lab, World Inequality Report 2022 (data on income and wealth inequality trends) wid.world.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF), Economic Inequality and Growth Reports (impact of inequality on economic stability) imf.org.

- Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (analysis of wealth concentration and its risks to democracy) piketty.pse.ens.fr.

- World Bank, Global Inequality and Economic Development Reports (data on the growing income gap) worldbank.org.