Franciscus the Economist - What the Pope Would Do With Power, Not Just Prayer

Pope Francis had consistently challenged the world to build an economy that serves people and the planet, not the other way around. Francisconomics explores what global policy might have looked like as economic doctrine.

Francis's Economic Blueprint: Beyond Doctrine to Design

Pope Francis had consistently challenged the world to build an economy that serves people and the planet, not the other way around. If he were an economist crafting policy, his agenda would center on human dignity, solidarity, and the common good – core themes of Catholic social teaching. His policies would disrupt the neoliberal order far more than any populist rebellion.

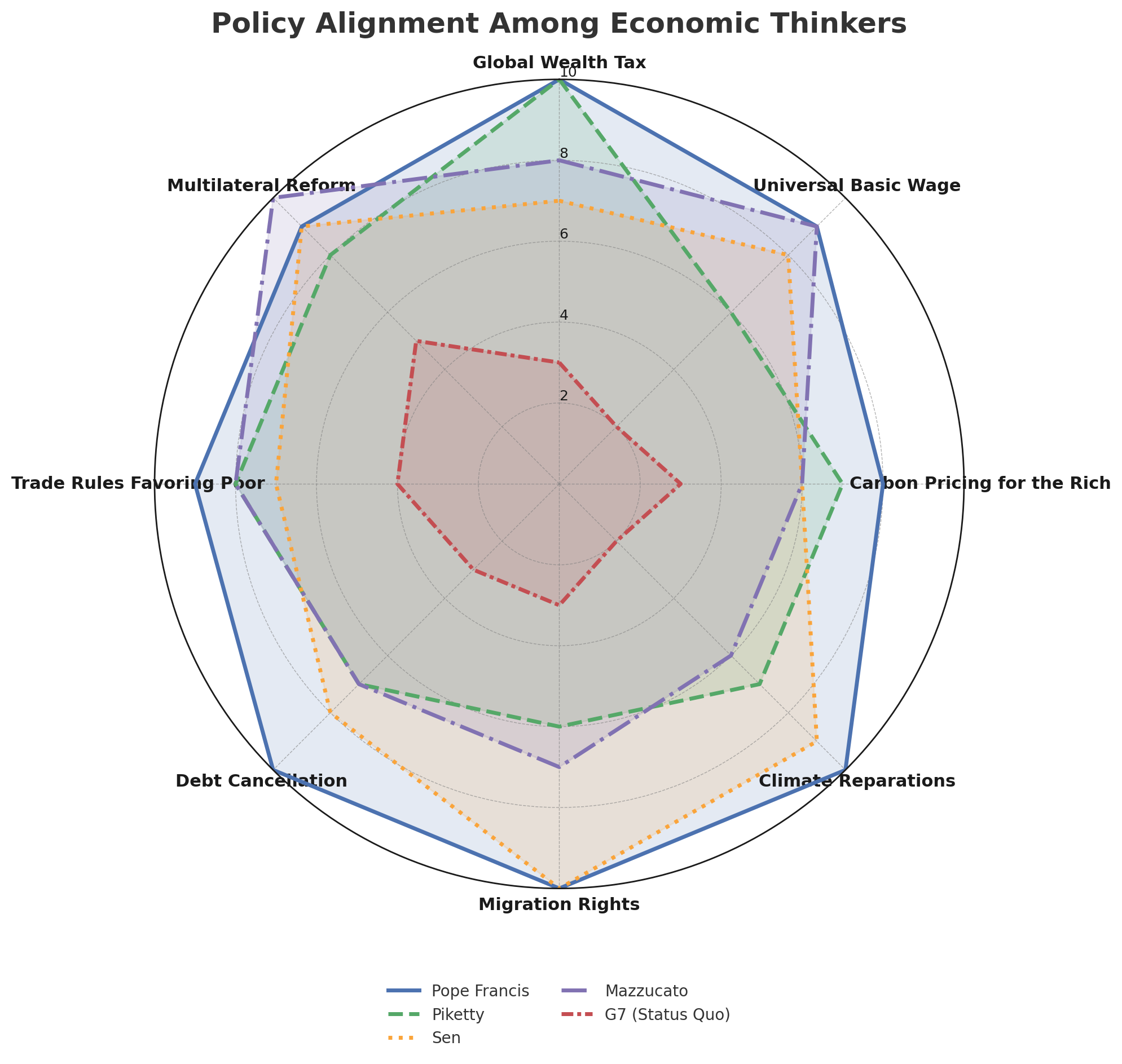

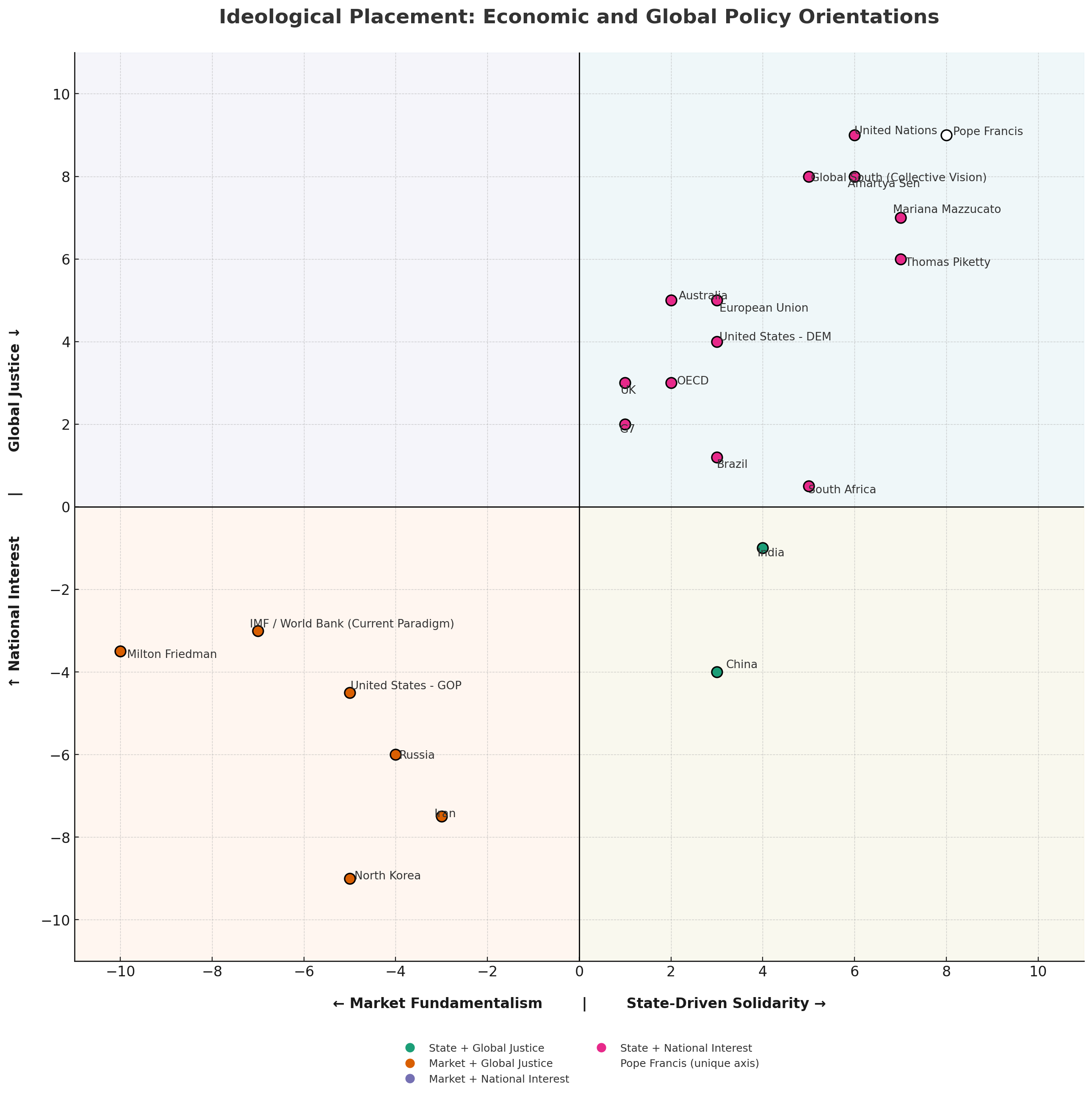

This article explores the economic and geopolitical policies Pope Francis would likely champion – from tackling wealth gaps and unfair trade to advocating debt relief, global taxes, climate justice, and humane migration policy – all grounded in his public teachings. It also compares his outlook with thinkers like Thomas Piketty, Amartya Sen, and Mariana Mazzucato, illustrating a convergence on key issues.

The result is a comprehensive picture of “Francisconomics”: a call for a moral economy that uplifts the poor, protects the earth, and fosters global fraternity.

| Key Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| 🏛️ | Pro-State Vision: Francis rejects market fundamentalism and favors public investment, wealth redistribution, and strong regulation. |

| 🌍 | Global Solidarity: His worldview prioritizes Global South justice, refugee rights, and ecological reparation over national interest. |

| 💰 | Inequality Is a Sin: A global wealth tax, debt forgiveness, and progressive fiscal systems are core to his economic theology. |

| 🛠️ | Dignity of Work: Universal basic wage, worker protections, and job guarantees reflect his emphasis on labor dignity. |

| ⚖️ | Fairer Trade & Finance: He critiques IMF/World Bank orthodoxy, calling for structural reform and ethical globalization. |

| ♻️ | Integral Ecology: Climate justice isn’t a side note—it’s a civilizational imperative with moral and economic consequences. |

| ✊ | Multipolar Reformist: Francis proposes a world order where international law and multilateralism replace dominance by the powerful few. |

Francis rejects market fundamentalism and calls for a moral economy shaped by state responsibility and solidarity.

Francis’s starting point is not GDP—it’s human dignity. Drawing from Catholic social teaching, he champions the idea that markets must serve the common good, not the other way around. He rejects “trickle-down” economics as a myth that “has never been confirmed by the facts”, and calls instead for what Amartya Sen might call capability-centered development. His vision aligns with Mariana Mazzucato’s call for “mission-oriented economies,” where the state has a proactive role in shaping markets for public benefit.

Francis’s economic doctrine is not merely redistributive—it’s transformational. He demands a moral realignment of economic goals, placing the poor and the planet at the center of every policy.

🔽 Click to Expand: Catholic Social Teaching and Francis’s Economic Philosophy

At the heart of Pope Francis’s economic philosophy are enduring principles of Catholic Social Teaching (CST): the inherent dignity of every person, the preferential option for the poor, solidarity with one another, and the pursuit of the common good. Francis often reminds us that “the lives of all take priority over the appropriation of goods by a few” vatican.va. He views extreme inequality and poverty not as unfortunate by-products of progress, but as systemic injustices – a “structural cause” of social ills that must be confronted vatican.va. In a 2014 address to grassroots movements, he affirmed that basic necessities “land, housing and work” are sacred rights, lamenting that “nowadays, it is sad to see that land, housing and work are ever more distant for the majority” vatican.va. Far from espousing any partisan ideology, Francis roots these convictions in the Gospel call to love the poor, stating “they do not understand that love for the poor is at the centre of the Gospel” vatican.va.

Integral human development is a key concept for Francis, much in line with economist Amartya Sen’s vision of development as expanding human capabilities. Pope Francis insists true progress must be person-centered – ensuring everyone can develop morally, spiritually, and materially – rather than fixating on GDP growth alone. “Development cannot be reduced to economic growth,” he echoes, stressing education, healthcare, and spiritual well-being as equally important. This holistic approach mirrors Sen’s capability approach (which broadened development metrics beyond income) and builds on the CST tradition of integral human development levyinstitute.org. Like Sen, Francis sees poverty as a deprivation of fundamental rights and opportunities; he thus advocates social structures that enable each person to “be an agent in their own redemption” vatican.va.

Solidarity vs. “Trickle-Down” – Perhaps Pope Francis’s most famous economic critique is of the laissez-faire, trickle-down ideology. In Evangelii Gaudium, he wrote with pointed skepticism: “Some people continue to defend trickle-down theories which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably bring about greater justice and inclusiveness… This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power” vatican.va. Such a statement could easily appear in a Thomas Piketty or Joseph Stiglitz essay. Francis rejects “magical” market thinking and calls for solidarity in action – “thinking and acting in terms of community” and “fighting against the structural causes of poverty and inequality” vatican.va. This emphasis on solidarity as a social organizing principle aligns with economists who argue that unchecked market forces won’t fix inequality; deliberate policy choices must.

🔽 Click to Expand:Comparisons with Progressive Thinkers

There is a striking convergence between Pope Francis and prominent economists who critique the status quo:

- Thomas Piketty (Inequality): Piketty’s data-rich analyses of widening wealth inequality bolster Francis’s moral alarm about the “gap separating the majority from the prosperity of the few” vatican.va. Piketty proposes global wealth taxes to curb inequality – a remedy Francis would likely favor given his concern that “widespread financial speculation and tax evasion” worsen inequality vatican.va. One scholar noted that “Piketty uncovers the kinds of inequality of which Catholic social teaching must take account,” and Francis provides the moral force by highlighting the human toll of those disparities theologicalstudies.net. Both call for vigorous state intervention to redistribute wealth for the common good. Francis’s assertion that “a minority’s earnings are growing exponentially” while most are left behind vatican.va reads like a pastoral version of Piketty’s empirical findings.

- Amartya Sen (Human-centered Development): Sen’s emphasis on human well-being, not just income, resonates with Francis’s calls to put “human dignity back at the centre” of economics vatican.va. Francis would agree with Sen that poverty is not only about low income but about exclusion from participation and lack of basic capabilities. In Fratelli Tutti, Francis warned that if “a society is governed primarily by the criteria of market freedom and efficiency, there is no place for such persons [the excluded], and fraternity will remain just another vague ideal” wherepeteris.comvatican.va. This could be seen as a moral echo of Sen’s critique of purely market-driven approaches that ignore equity. Francis’s frequent use of the term “integral human development” (also the name of a Vatican office he created) reflects a development paradigm very much in harmony with Sen’s – one that demands social inclusion, education, healthcare, and environmental care as parts of true progress, not afterthoughts.

- Mariana Mazzucato (Common Good and the State’s Role): Mazzucato argues for a mission-oriented, inclusive economy where the state, private sector, and civil society co-create value for public purposes. Pope Francis has actively engaged her work – even inviting her to the Vatican. In November 2024, a historic dialogue in Rome saw Francis (via a message), Prof. Mazzucato, and Barbados PM Mia Mottley “call for an economics of the common good,” urging that refocusing the global economy and finance around the common good needs to be a global priority ucl.ac.ukucl.ac.uk. This notion of the common good is a pillar of CST and a refrain in Francis’s teachings. Rather than accepting markets as neutral, Francis insists markets must be guided by moral purposes. He laments ideologies which “reject the right of states, charged with vigilance for the common good, to exercise any form of control” over markets vatican.va. In tune with Mazzucato, he sees a positive role for public authorities: smart regulation, social investment, and partnership with grassroots movements. Both would champion “mission-driven” economic policies – e.g. massive public efforts to fight climate change or inequality – instead of leaving outcomes to chance. Indeed, Francis praises initiatives that “actively shape markets…to deliver shared goals” and calls on governments to have “proactive economic policies” that create jobs and foster “diverse productive creativity,” rather than austerity or laissez-faire vatican.va. This mirrors Mazzucato’s view that the economy can be purposefully steered toward innovation and inclusion from the start ucl.ac.uk.

Other economists and thinkers could be named – Joseph Stiglitz’s critiques of neoliberal globalization, Kate Raworth’s doughnut model balancing human needs and planetary boundaries, Jeffrey Sachs’s focus on sustainable development – all find an ally in Francis. The pope’s economic vision is not a technical blueprint but a moral framework: one that elevates equity, ethical stewardship, and global solidarity. In the following sections, we break down how Pope Francis, as an economist-policy maker, might approach specific areas of economic and geopolitical policy.

A global wealth tax, fair taxation, and structural reform aren't suggestions—they are ethical imperatives.

No issue haunts Francis more than inequality. He views it not as a policy failure, but a structural sin. Echoing Piketty’s empirical alarms, Francis points to how “a tiny minority owns half the world’s wealth” while billions remain excluded. He would likely endorse a global wealth tax, as well as progressive income taxation, clampdowns on tax evasion, and international financial transparency.

Crucially, he condemns the “globalization of indifference”—a condition where inequality becomes normalized, and the suffering of others invisible. His policies would aim to reverse this moral numbness with fiscal instruments and legal safeguards.

🔽 Click to Expand: Fighting Wealth Inequality and Poverty

Pope Francis regards extreme wealth inequality as a moral scandal and a threat to social cohesion. He famously tweeted “Inequality is the root of social evil,” capturing his belief that vast disparities in wealth erode the bonds of society and give rise to violence and despair vatican.va. In his view, economic inequality is not only unjust in itself but “gives rise to new forms of violence which threaten the fabric of society” vatican.va. If designing policy, Francis would emphatically prioritize narrowing the wealth gap – through taxation, social programs, and empowering the poor.

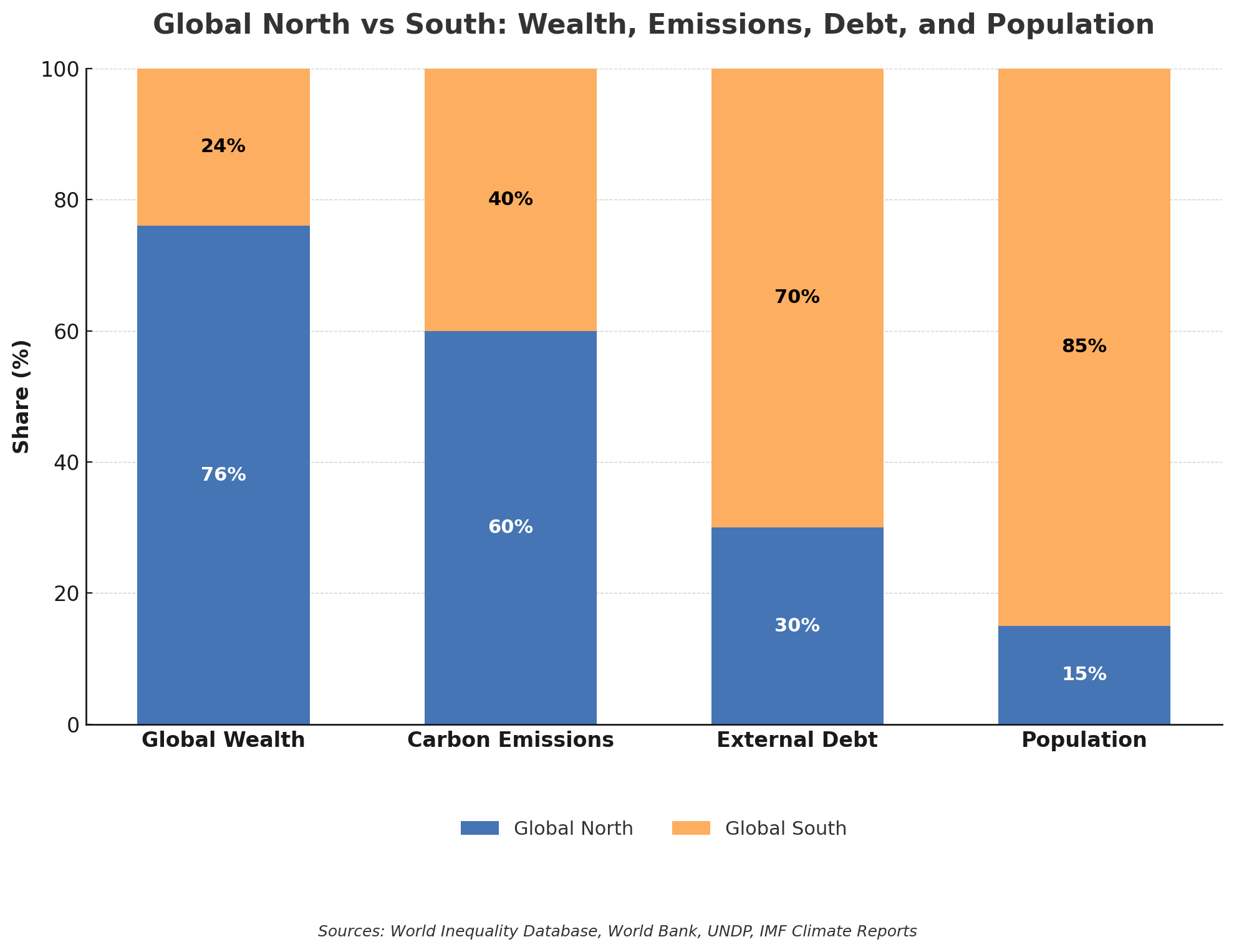

He has drawn attention to the outsized wealth of a tiny elite amid the suffering of many. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Francis wrote that we cannot simply return to “an unequal and unsustainable model of economic and social life, where a tiny minority of the world’s population owns half of its wealth” reuters.com. That description aligns with real-world data: as of 2021, the richest 10% of people took home 52% of global income, while the poorest half earned just 8% wir2022.wid.world. The wealth distribution is even more skewed – the richest 10% own 76% of global wealth, whereas the bottom 50% own only 2% wir2022.wid.world. Francis continually raises such facts to prick the conscience of the comfortable. He decries a “globalization of indifference” whereby the plight of the poor is ignored while the affluent live in excess vatican.va vatican.va.

Global distribution of income and wealth remains grossly imbalanced. Pope Francis highlights that a “tiny minority” controls vast riches while billions struggle. In 2021, the richest 10% received over half of all income and held three-quarters of all wealth, whereas the poorest 50% struggled with single-digit shares wir2022.wid.world wir2022.wid.world. Such stark inequality is a core concern in Francis’s calls for economic reform.

Progressive Taxation and Wealth Redistribution: To address these inequalities, Pope Francis would likely support robust redistributive policies. He has praised efforts to tax wealth and high incomes fairly. In fact, the Vatican under his watch has joined global calls for tax justice. Francis agrees that “we must demand political will to put an end to the impunity of tax evaders and build a fairer, global tax system”, as one international statement he supported put it taxjustice.net taxjustice.net. He views paying one’s fair share of taxes as a moral duty and has condemned tax evasion as “stealing” from the common good theguardian.com theguardian.com. We can infer he’d back measures like a global minimum corporate tax, clamping down on tax havens, and even ideas akin to Piketty’s global wealth tax to prevent excessive accumulation at the top. In Evangelii Gaudium, Francis linked the “widespread…self-serving tax evasion” by the wealthy to the oppression of the poor, noting it has “taken on worldwide dimensions” vatican.va. As an economist, he would press for international cooperation to close loopholes that allow the richest individuals and multinational corporations to avoid taxes – thereby reclaiming resources to fund social programs.

Social Safety Nets and Poverty Eradication: Pope Francis’s overriding concern is for the poor and vulnerable. He insists that economies must “ensure that all can share in the resources of this world”, invoking the longstanding Catholic teaching on the universal destination of goods. In practical terms, he would champion strong social safety nets (food security, healthcare, housing assistance) and policies like a living wage or even universal basic income for those in need. Notably, in Easter 2020, Francis issued a bold proposal: “This may be the time to consider a universal basic wage which would acknowledge and dignify the noble, essential tasks [of all workers]… and ensure no worker is without rights” levyinstitute.org. This idea, coming amid the pandemic, was meant to guarantee everyone a minimal income for dignity – a clear signal that he supports direct measures to end extreme poverty. As an economic policy-maker, Francis would likely push for targets like eradicating hunger and homelessness (he calls these conditions “criminal” in a world of plentyweforum.org). He would redirect national and international budgets toward poverty alleviation, aligning with the UN Sustainable Development Goals but urging even more urgency and moral clarity.

Challenging “Trickle-Down” Myths: Francis’s harsh critique of “trickle-down” economics signifies that he would reject policies favoring the wealthy in hope benefits magically “trickle” to the poor. Instead of tax cuts for the rich or deregulation under the promise of growth, he’d advocate bottom-up empowerment – investing in education, healthcare, job training, and small businesses for the marginalized. In his words, “in addition to recovering a sound political life not subject to the dictates of finance, we must put human dignity back at the centre and on that pillar build the alternative social structures we need” vatican.va. This implies restructuring the economy so it works for everyone, not just letting the wealthy few dictate terms. In sum, to fight inequality, Pope Francis would employ the state’s fiscal and regulatory powers to lift up those at the bottom (through social support and just wages) and to temper those at the very top (through taxation and accountability), always with an eye to the common good rather than elite interests.

Work is not a means to profit—it is a source of human dignity.

For Francis, labor is not a commodity—it is co-creation with God. He supports full employment policies, worker protections, collective bargaining, and perhaps most strikingly, a universal basic wage—not just as a poverty alleviation tool, but as a recognition of the dignity of informal and underpaid labor.

This proposal aligns with modern UBI debates but diverges by rooting itself in the theology of work. In his own words: “It is imperative to have a proactive economic policy directed at… jobs to be created, not cut.”

🔽 Click to Expand: Dignity of Work and Labor Rights

Few topics are closer to Pope Francis’s heart than the dignity of labor. Drawing from Catholic teaching (and his own experience in working-class Buenos Aires), he proclaims that meaningful work at just wages is essential for human dignity. “We get dignity from work,” Francis said plainly; “work…anoints us with dignity” vaticannews.va vaticannews.va. If setting economic policy, he would prioritize full employment, workers’ rights, and decent wages. In his ideal economy, “there might be work for all and that it might be dignified work, not the work of a slave” vaticannews.va.

“Work for All” – Full Employment and Job Creation: Francis often laments high unemployment, especially among youth, as a “social plague.” He sees joblessness not just as lost income but an assault on human dignity, since being unable to contribute through work breeds despair. Thus, a Francis-inspired policy agenda would seek full employment, possibly through government job guarantees or robust public investment. Indeed, economists working with the Vatican have discussed a Job Guarantee to ensure “everyone able and willing to work can have a job with dignity”. Pope Francis praised grassroots initiatives that create jobs for the excluded – for example, cooperatives of waste-pickers (cartoneros) in Argentina who found purpose and income in recycling levyinstitute.org. We could imagine him supporting public works programs that both employ people and meet social needs (infrastructure, care for the elderly, environmental rehabilitation, etc.). “It is imperative to have a proactive economic policy directed at…jobs to be created and not cut,” he wrote, rejecting the notion that labor must be sacrificed for efficiency vatican.va. Even in international gatherings, he has encouraged leaders to aim for zero unemployment as a policy goal, rather than accepting joblessness as inevitable.

Just Wages and Workers’ Rights: For Pope Francis, having a job is not enough – it must be a job with rights and fair pay. He recalls that “to deprive an employee of wages is to commit murder” (quoting scripture) and that “every injustice inflicted upon a person who works means trampling upon human dignity” vaticannews.va. Therefore, he would champion living wage laws that ensure no full-time worker remains in poverty. He likely supports stronger collective bargaining and labor unions as well, in line with Catholic teaching that unions are “the voice of the workers” and vital for justice (Laborem Exercens, St. John Paul II). Francis has met union delegations and often speaks of protecting “labor rights” as central to the common good vatican.va. We can surmise he’d back policies like higher minimum wages, pay equity, and enforcement of workplace safety and hour laws. The pope has specifically decried the plight of workers “forced to work for a pittance.” He notes that even today “many men and women…are slaves to forced labor and poorly paid…this doesn’t happen only in Asia… it happens here”, calling out exploitative labor practices globally vaticannews.va. To him, phenomena like sweatshops, child labor, or migrant labor abuse are intolerable evils to be abolished.

Additionally, Francis would fight against the modern trend of precarious work (gig economy, zero-hour contracts) that leaves workers insecure. He stresses that stable employment is part of dignity – uncertainty and exploitation in the labor market must be remedied by law and social protections. In the context of the digital/automation revolution, he might advocate policies for retraining workers and reducing working hours without reducing pay (so the benefits of productivity are shared as leisure, not just profits). The principle is that the economy must serve the worker, not use up and discard people (what he calls the “throwaway culture”).

Universal Basic Wage and Social Security: As mentioned, Francis’s notable proposal of a universal basic wage indicates he is open to bold measures to support workers, especially those in informal sectors or impacted by crises. He differentiated it from a general basic income by tying it to the dignity of labor – essentially a floor on income that values even unpaid or underpaid work (like caregiving or community service) levyinstitute.org levyinstitute.org. In practice, he might design a form of guaranteed income for all adults, or at least for all workers including those in the informal economy, funded perhaps by taxes on wealth or carbon (since he links ecological duty with social justice). Furthermore, Pope Francis certainly supports strong social security systems – unemployment insurance, healthcare, pensions – as part of what makes work humane (because workers know they and their families won’t fall into ruin if they lose a job or retire). His economic plan would thus robustly reinforce social insurance and possibly expand it (for example, by recognizing homemakers or gig workers in benefit systems).

In summary, Pope Francis’s labor policy would hold as a non-negotiable that every person who can work should have the chance to do so, and every person who works should earn enough to live in dignity and have their basic rights respected. Policies like full-employment programs, increased unionization, living wage standards, and perhaps a universal basic income/wage all fit neatly into this vision. Such steps echo what many labor-oriented economists and moral leaders have long advocated, putting Francis firmly on the side of those who see labor not as a cost to be minimized, but as the very purpose of economic activity – “the continuation of the work of God” that allows men and women to be co-creators and care for their families vaticannews.va vaticannews.va.

Trade must uplift the poor—not reward the already-powerful.

Francis critiques the existing global trade system as exploitative and asymmetrical. He would likely support:

- Trade protections for developing economies

- International labor and environmental standards enforcement

- Equitable commodity pricing

His idea of “ecological debt” implies that wealthy nations owe reparations not just for colonization, but for ongoing exploitation via unfair trade and resource extraction. He champions a world where trade reflects fraternity, not dominance.

🔽 Click to Expand: Trade Justice and Fair Globalization

Pope Francis approaches international trade and globalization through the lens of justice for the poor and development with dignity. He is critical of a laissez-faire global trade system that can enrich wealthy nations and corporations at the expense of poorer communities. As an economist, he would likely press for reforms to make trade rules fairer, protect vulnerable economies, and ensure that globalization does not mean marginalization.

Critique of Neoliberal Free Trade: In Fratelli Tutti, Francis observes that “certainly, the dogma of neoliberal faith” – the belief that free-market trade automatically benefits all – has failed to solve society’s deepest problems vatican.va. He specifically calls out the blind faith in market freedom: “[Some] would have had us believe that freedom of the market was sufficient to keep everything secure. Yet…the pandemic has demonstrated that not everything can be resolved by market freedom” vatican.va vatican.va. For decades, global institutions often pushed developing countries to open their markets rapidly, sometimes undermining local industries and farmers. Pope Francis has witnessed the fallout of such policies, for example in Latin America where sudden trade liberalization and austerity in the 1990s led to social pain. He would therefore favor a model of trade justice over unfettered free trade – meaning trade arrangements should be evaluated by how they impact the poor and whether they uphold human rights and environmental standards.

Concretely, Francis might support allowing poorer countries to protect certain sectors (like small farmers or fledgling industries) from being swamped by foreign competition. He has voiced concern that the global economic system often treats the poor as an afterthought: “The problems of the poor are brought up as an afterthought… if not treated merely as collateral damage. Indeed…they frequently remain at the bottom of the pile” vatican.va vatican.va. This suggests he’d critique trade deals that ignore labor and environmental impacts in poorer nations. Instead, he’d advocate fair trade initiatives – e.g. ensuring farmers get fair prices, banning exploitative labor in supply chains, and giving developing countries more policy space to achieve food security and industrialization.

Empowering the Global South in Trade: Pope Francis consistently lifts up the perspective of the Global South. He notes that poorer countries often face “forms of international pressure which make economic assistance contingent on certain policies” (for instance, being forced to adopt strict population control or austerity in exchange for aid) vatican.va vatican.va. He strongly criticizes this and also the “commercial imbalances” that favor rich nations vatican.va. In Laudato Si’, Francis points out an “ecological debt” owed by the Global North to the South, partly due to the North’s historical over-consumption of resources and exploitative trade vatican.va vatican.va. He cites how raw materials exported from poor countries to fuel Northern consumption often leave behind environmental damage and depleted economies in the South vatican.va vatican.va. This implies he would push for more equitable terms of trade – perhaps commodity agreements that ensure sustainable prices, technology transfers to help value-added production in the South, and compensation for resource extraction.

Francis would also encourage regional trade cooperatives among developing nations (South-South trade) as a way to reduce dependency on Northern-dominated markets. And he’d insist that voices of developing countries be heard in setting the rules. For example, he might support giving the African Union, Latin American blocs, etc., greater say in the World Trade Organization (WTO) decision-making. He has praised efforts to “facilitate access to the international market on the part of countries suffering from poverty and underdevelopment” vatican.va – meaning he supports measures to help poorer nations integrate into global trade on fair terms (like preferential treatment or aid-for-trade programs).

Regulating Multinationals and Preventing Exploitation: A major aspect of trade justice for Francis is addressing the power of multinational corporations. In scathing terms, he noted how some multinationals exploit weaker countries: “Often the businesses which operate this way are multinationals. They do here [in poor countries] what they would never do in developed countries… after ceasing their activity and withdrawing, they leave behind great human and environmental liabilities – unemployment, abandoned towns, depleted natural reserves, polluted rivers…” vatican.va vatican.va. This “race to the bottom” in labor and environmental standards is a byproduct of unregulated globalization. Pope Francis would support international standards or treaties to hold companies accountable globally – ensuring they cannot evade justice by moving operations to jurisdictions with lax rules. He has alluded to the need for stronger global governance to enforce labor and environmental norms so that, for instance, a factory collapse or toxic spill in a poor country is not treated with impunity. We can imagine him backing the current UN initiative for a binding treaty on business and human rights.

In practical policy, Francis might advocate: requiring human-rights due diligence for companies, sanctioning corporations that engage in abuse abroad, and closing loopholes that allow profits to be extracted without benefiting the host country (tying back to tax justice). All these measures aim to make globalization “civilized” – i.e., guided by ethics and solidarity, not just profit.

Finally, Francis’s idea of “social and economic inclusion” on a global scale likely means he would want trade agreements to include provisions for development aid, technology sharing, and capacity building. Trade should not just be free, but fair and developmental. He often warns against a globalization that homogenizes culture and disregards the poor. Instead, he envisions a globalization of solidarity: where “the value proper to each creature” and each community is respected vatican.va, and where we truly treat each other as members of one human family trading and collaborating for mutual benefit, not exploiting one another.

Francis challenges the legitimacy of a financial system that subjugates the weak.

Calling foreign debt “a way of controlling poor countries”, Francis backs full or partial debt cancellation, especially in crisis contexts. He also condemns speculative finance, proposing strict regulation of high-frequency trading, lending practices, and tax havens.

Unlike technocratic solutions, his approach fuses ethical obligation with structural reform—an economic jubilee rooted in Fratelli Tutti rather than fiscal orthodoxy.

🔽 Click to Expand: Debt Relief and Financial Reform

In Pope Francis’s economic worldview, excessive debt and a speculative financial system are major barriers to justice. He has been an outspoken advocate for relieving the debts of poor nations and for reorienting finance to serve the real economy. As an economist formulating policy, he would likely push for systemic debt relief initiatives, stricter financial regulation, and a financial system geared toward social goals rather than short-term profit.

Debt Justice for Poor Countries: Francis often highlights the crushing burden that international debt places on developing nations. He bluntly stated, “The foreign debt of poor countries has become a way of controlling them” vatican.va – a striking indictment of how loans can undermine sovereignty. During COVID-19, he called on the world’s financial leaders (the IMF and World Bank) to significantly reduce or forgive the debts of the poorest nations, especially given the pandemic’s toll reuters.com. In an April 2021 letter to those institutions, he wrote that a spirit of global solidarity “demands at the least a significant reduction in the debt burden of the poorest nations”, tying it to the notion that it’s immoral for rich creditors to demand full repayment while people are suffering reuters.com. If crafting policy, Pope Francis would support measures like debt moratoria, restructurings, and outright cancellations (jubilees) for low-income countries, particularly when debt servicing comes at the expense of basic needs. He likely endorses proposals for an international debt workout mechanism – a fair process to arbitrate debt relief – so that countries don’t have to choose between paying debt and caring for their citizens.

Francis also links this to his idea of “ecological debt”: wealthy nations owe a debt to poorer ones for centuries of resource extraction and pollution. Thus, in climate negotiations, he would argue that part of climate finance or adaptation funding is effectively repayment of that ecological debt vatican.va vatican.va. Practically, he’d push for richer countries to provide grants (not just loans) to poorer countries for sustainable development, as a matter of justice. He praised efforts like the Jubilee 2000 campaign (which successfully pressed for debt cancellation around the turn of the millennium) and would likely revive that ethos for the 21st century: possibly calling for a new Jubilee for debts in the post-Covid era.

Ethical Financial System – “No to an Economy of Exclusion”: Pope Francis famously said “Money must serve, not rule!” and that we should say “no to a financial system which rules rather than serves” vatican.va. He regards the modern financial sector’s excesses – speculative trading, complex derivatives, usury-level interest rates – as deeply problematic. In Evangelii Gaudium, he observed how “the current financial crisis…originated in a profound human crisis: the denial of the primacy of the human person. We have created new idols… in the idolatry of money and the dictatorship of an impersonal economy lacking a truly human purpose” vatican.va. Based on this, a “Franciscan” economic policy would impose strong regulation on financial markets to curb harmful speculation and ensure finance supports real investment in businesses and jobs. He would likely favor policies such as: a financial transaction tax (to dampen high-frequency trading and generate revenue for social causes), tighter controls on risky banking activities (reinstating Glass-Steagall-type separation of commercial and investment banking, for example), and closing down shadow banking loopholes.

Francis has singled out practices like “the accumulation of interest” that “make it difficult for countries to realize their potential” vatican.va – indicating support for interest rate relief or regulation to prevent usury. He also lambastes “widespread corruption and self-serving tax evasion” vatican.va; in the financial context, this means he’d push for transparency (e.g., beneficial ownership registries to combat money laundering) and for cracking down on illicit financial flows from poor countries. Essentially, reforming global finance for Francis means taming the speculative, greed-driven aspects and reorienting capital toward productive, inclusive uses.

Democratizing Economic Governance: Another aspect is giving developing countries a greater voice in global financial governance. In his IMF/World Bank message, Francis also mentioned that poor nations should “be given a greater say in global decision-making” on finance reuters.com. Thus, he would advocate reforms at the IMF and World Bank – for instance, adjusting voting shares, diversifying leadership, and rethinking conditionality policies that impose austerity. He might support the creation of new funds or support mechanisms under the United Nations (which he tends to trust more as a multilateral forum) to guide global finance in solidarity. His vision of global solidarity includes emergency support that doesn’t trap countries in debt. So, he likely would favor issuing more Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) at the IMF and reallocating them to poor countries, or establishing permanent mechanisms for climate and health financing that are not debt-based.

In sum, Pope Francis’s stance on debt and finance is that these should be instruments for human development, not instruments of domination or greed. “The dignity of the human person and the common good rank higher than the comfort of those who refuse to renounce their privileges,” he wrote vatican.va, a clear rebuke to those who would prioritize creditor profits or market freedoms over human lives. If he set policy, we would likely see major debt cancellations, “debt swaps” where debts are forgiven in exchange for local investments in health or environment, and a push to curtail speculative finance through regulation and global coordination. His ultimate goal would be a financial system anchored in solidarity, where, for example, excess liquidity in rich countries is mobilized (via public banks or global funds) to invest in impoverished communities, and where no country is strangled by debt so much that it cannot provide education, food, and healthcare to its people.

Climate justice isn’t a layer—it's the core of his economic vision.

Francis is perhaps one of the major world leaders to center environmental degradation in an economic critique. Laudato Si’ positions climate justice as inseparable from economic justice. He would:

- Phase out fossil fuel subsidies

- Institute carbon pricing targeting high emitters

- Redirect public investment to green infrastructure

- Demand climate reparations from wealthy countries

His message is clear: “We are faced not with two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather one complex crisis which is both social and environmental.”

🔽 Click to Expand: Climate Economics and Sustainable Development

Pope Francis is globally renowned for his environmental leadership – he sees the ecological crisis as inseparable from the economic crisis. In Laudato Si’, he articulated a vision of integral ecology, where economic decisions must account for environmental impact and social justice. If Francis were shaping economic policy, climate and sustainability priorities would be front and center. He would support aggressive action to cut greenhouse emissions, protect the environment, and ensure the costs and benefits of the transition are equitably shared.

Climate Justice – Protecting the Poor and the Earth Together: Francis emphasizes that the poor suffer the worst effects of climate change despite contributing least to the problem. He speaks of a “profound injustice” in this and insists on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities in climate action vatican.va vatican.va. For instance, “the warming caused by huge consumption on the part of some rich countries has repercussions on the poorest areas of the world” (e.g. droughts in Africa) vatican.va vatican.va. As a result, he would advocate economic policies that make polluters (usually wealthy individuals, industries, and countries) pay for the damage and fund adaptation for the vulnerable. We can imagine Pope Francis supporting a global carbon pricing mechanism – perhaps a carbon tax or cap-and-trade – designed in a way that revenue is transferred to poorer nations and communities for climate resilience. He explicitly noted the need “to calculate the use of environmental space… which has been occupied by the gas emissions of the industrialized countries”, hinting at carbon-budget accountability vatican.va vatican.va.

In practical terms, Francis’s climate economics would entail: rapidly phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and redirecting those funds to renewable energy and green jobs; investing in sustainable agriculture and conservation (with special attention to indigenous peoples’ rights, as he did in the Amazon Synod); and creating compensation funds for communities already facing climate damage (akin to the “Loss and Damage” fund now being set up globally). He called it “a basic and ecological debt” that the North owes the South vatican.va – so he would insist wealthy countries follow through on climate finance commitments (like the $100bn per year pledge) and likely urge them to go further.

Sustainable Development and the Circular Economy: Francis does not reject economic development, but he insists it must be redefined. He promotes the concept of sustainable and integral development – growth that respects human rights and planetary boundaries. He would likely support the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but push countries to truly embed them into budgets and policies, not just pay lip service. For example, he might advocate laws requiring environmental impact assessments for all major economic projects, strong enforcement of pollution controls, and incentives for clean technology. In Laudato Si’, Francis discusses moving away from a “throwaway culture” towards a circular economy where recycling, reusing, and reducing waste are key vatican.va vatican.va. Policy-wise, that could mean promoting industries in recycling and waste management (notably, he has praised the work of waste recyclers as mentioned above), banning single-use plastics (something the Vatican City itself has done under his tenure), and supporting innovation in sustainable materials.

Francis also highlights the importance of biodiversity and preserving ecosystems. He would likely advocate for economic metrics beyond GDP – similar to how Amartya Sen and others have argued – incorporating measures of environmental health and social well-being. He might support governments adopting “doughnut economics” frameworks (which ensure no one falls short on life’s essentials while not overshooting ecological limits). Land use policies under Francis’s economics would balance development with the rights of indigenous and local communities to manage their environment. He has spoken against rampant deforestation and resource grabs, for instance condemning proposals to “internationalize” the Amazon that actually mask corporate interests vatican.va.

Global Climate Cooperation and Institutions: On the global stage, Pope Francis calls for stronger multilateral action to address climate change. In 2015 he threw his moral weight behind the Paris Climate Agreement. By 2023, in his exhortation Laudate Deum, he lamented that promised actions were falling short and urged more binding commitments. He wrote of the “absence of supranational institutions… capable of enforcing commitments” on the environment vaticannews.va vaticannews.va. Thus, as a policy-maker, he might propose creating or empowering a global climate authority under the UN that can ensure countries and corporations meet their targets. This could include enforcement mechanisms or sanctions for non-compliance with emissions reductions, which is a bold idea in line with his quote about “more effective world organizations, equipped with the power to provide for the global common good…the sure defense of fundamental human rights” vaticannews.va. Such words echo calls for reforming international law to treat ecological destruction (ecocide) as an international crime and to strengthen treaties.

Francis’s climate stance is also about just transition: making sure that workers and communities dependent on fossil fuel industries are not left behind as we green the economy. He often speaks of the need to create new jobs in renewable energy and to retrain workers – bridging his concern for labor with climate action.

Importantly, he ties the climate crisis to overconsumption by the rich. He noted that the lifestyle of wealthy individuals has an outsized footprint: for instance, “the richest 1% [mostly in the global north] produce as much carbon pollution as the poorest 5 billion people” (two-thirds of humanity) theguardian.com. He would thus endorse policies targeting luxury emissions – e.g., higher taxes or bans on things like private jets, mega-yachts, and mansions, as some proposals have suggested. Indeed, an Oxfam study found that just 50 of the world’s richest billionaires emit more CO₂ in 3 hours (via yachts, jets, etc.) than an average person does in a lifetime theguardian.com theguardian.com. Pope Francis cited such inequality of emissions to argue that the rich have an urgent duty to cut back and help others adapt theguardian.com theguardian.com. He would likely applaud recent ideas like France’s ban on short-haul flights or calls for a frequent-flyer levy – anything that curbs unnecessary pollution by the affluent while protecting the poor.

In summary, Pope Francis’s economic policy on climate and the environment would vigorously pursue decarbonization and ecological sustainability, guided by the principles of justice. He would implement climate action in a way that lifts up the poor (through funding and technology transfer) and holds accountable those most responsible for pollution. He envisions an economy where growth is not at odds with nature, but rather growth is redefined: “technological and economic development which does not leave in its wake a better world and an integrally higher quality of life cannot be considered progress”, he wrote in Laudato Si’ vatican.va vatican.va. His policies would therefore aim for what he calls “integral ecology” – economic arrangements that simultaneously protect the earth, provide dignified livelihoods, and enable all people to flourish in harmony with creation.

Welcoming the migrant is not charity—it is a structural obligation.

Francis’s migration policy flows from solidarity, not security. He supports:

- Legal pathways for migrants

- Safe working conditions and equal rights

- International responsibility sharing for refugees

- Development in origin countries to reduce forced migration

He links migration to global inequality and exploitation. For Francis, the refugee is not a threat, but a test of our humanity.

🔽 Click to Expand: Migration Policy and Economic Migration

Pope Francis has been called the “Pope of the peripheries” for his constant attention to migrants, refugees, and those on society’s margins. He approaches migration not just as a political issue but as a deeply human and economic one: people move largely due to wars, inequities, and lack of opportunity. In a Francis-inspired policy framework, migration would be managed with compassion and international cooperation, addressing root causes and protecting migrants’ rights.

Tackling Root Causes: First and foremost, Francis would aim to reduce the forced economic migration that stems from desperation. He notes that many migrants “are seeking opportunities for themselves and their families. They dream of a better future and want to create the conditions for achieving it” vatican.va. Rather than viewing this as a threat, he sees it as a legitimate human aspiration when local conditions are dire. Thus, he advocates helping people thrive in their home countries so that migration is a choice, not the only escape from poverty or violence. “Development of their countries of origin” should be promoted “through policies inspired by solidarity”, he writes vatican.va. In practice, this means Francis would support increasing development aid targeted at job creation, education, conflict resolution, and climate adaptation in the Global South. He has warned against the attitude of some who say rich countries should limit aid so that poor countries “hit rock bottom” and supposedly fix themselves – he calls that out as cruel and short-sighted vatican.va. Instead, he’d push for a global effort to invest in areas that export migrants, akin to a modern Marshall Plan for regions in Africa, Latin America, and Asia that suffer from underdevelopment. This aligns with economists who argue that investing in source countries is key to managing migration long-term.

Humane Treatment and Integration: Pope Francis consistently pleads “may we welcome, protect, promote, and integrate” migrants – a summary of his four-fold approach (from his 2018 message on migrants and refugees). If setting policy, he would insist on humane treatment of migrants at borders and ample support for their integration into receiving societies. He would oppose harsh measures like family separation, indefinite detention, or refoulement of asylum seekers to danger. In Fratelli Tutti, he wrote “Migrants are not seen as entitled like others to participate in social life, and it is forgotten that they possess the same intrinsic dignity as any person” vatican.va. To correct this, he’d urge countries to provide migrants and refugees basic services, legal status, and paths to citizenship. He also believes host communities benefit from newcomers: “For the communities and societies to which they come, migrants bring an opportunity for enrichment and the integral human development of all… If they are helped to integrate, immigrants are a blessing, a source of enrichment” vatican.va. This positive outlook suggests policies like language and job training for immigrants, anti-discrimination laws, and programs that encourage cultural exchange.

Francis is realistic that integration can be challenging, and he acknowledges citizens’ fears, but he appeals to the better angels of our nature. He’d likely support a global sharing of responsibility for refugees – criticizing how a few countries or frontline states bear most of the burden. He praised countries like Jordan, Lebanon, Italy, and Greece for accepting many refugees and gently scolded wealthier nations that shirk solidarity. We could expect him to endorse agreements to relocate asylum seekers across many countries so that no one nation is overwhelmed, very much in line with the Global Compact on Migration which emphasizes international cooperation.

Migrant Labor and Rights: Many migrants are economic migrants who end up doing essential but low-paid work in richer countries (agriculture, caregiving, construction). Pope Francis draws attention to their often precarious conditions. He would back stronger labor protections for migrant workers, to prevent exploitation like human trafficking or slave-like conditions. He called human trafficking “a source of shame for humanity”, linking it to forced migration and economic desperation vaticannews.va. Policies he’d favor include: cracking down on labor traffickers and smugglers, granting migrants work permits and rights so they aren’t pushed into illegality, and ensuring they have access to justice if abused.

Additionally, Francis might advocate for circular migration schemes or development-linked migration. For example, allowing seasonal workers from poorer countries to earn money abroad and return with skills, or twinning cities to facilitate exchange of labor while investing in local development. His aim would be to make migration safe, orderly, and voluntary, consistent with human dignity.

Opposing Nativism and Scapegoating: On the geopolitical front, Francis has been a vocal critic of xenophobia and populist nationalism that demonizes migrants. He notes the rise of rhetoric that the poor (including migrants) are “dangerous and useless” while the rich see themselves as benefactors vatican.va. As a moral leader, he denounces this “simplistic belief” and would shape policies that combat misinformation about migrants. For instance, he’d encourage public campaigns highlighting migrants’ contributions and foster encounters between locals and newcomers (he often speaks of the “culture of encounter” as the antidote to fear).

In summary, a Pope Francis-influenced migration policy would be one of compassionate welcome and international solidarity: invest in development to reduce forced migration; open legal pathways for those who do migrate (so they need not risk their lives via smugglers); ensure humane reception (no camps lacking basic needs or pushbacks at sea); and actively support migrants’ integration as equal members of society. He encapsulates this approach by reminding us that “we are all brothers and sisters” (Fratelli Tutti means “all brothers”), and that our common humanity must prevail over partisan divides. He even extends this to a call for recognizing global citizenship in some form – asserting that every person has the right to migrate to seek a life of dignity and the right not to be forced to migrate. Economic policy under Francis would treat migration as a structural issue tied to injustice: fix the injustice, and migration becomes better managed and more mutually beneficial.

Francis calls for a new global order built on law, human dignity, and planetary solidarity.

On the world stage, Francis calls for a reconfiguration of global power. He advocates:

- Reform of the IMF, World Bank, and WTO to amplify Global South voices

- Strengthening the UN as a guardian of ecological and social rights

- Regulation of multinational corporations abroad

- Support for grassroots movements as actors in global governance

His orientation is multipolar, dialogical, and anti-imperial—not aligned with China or the U.S., but with the world’s poor. “No one is saved alone,” he writes—so institutions must reflect that interdependence.

For a more comprehensive overview of global ideological alignments and cooperative behaviors, see The Political GPS: Exclusive Insights into Global Ideological and Cooperative Alignments available here.

🔽 Click to Expand: Global Institutions, Corporations, and Geopolitical Orientation

Pope Francis’s perspective on international economics is profoundly shaped by his Global South viewpoint and a desire for a more multipolar, inclusive world order. He often critiques the power imbalances in global institutions and urges reforms so that these bodies truly serve all humanity, not just the wealthy or powerful nations. Simultaneously, he navigates geopolitics with an emphasis on dialogue and peace, often implicitly challenging U.S.-led neoliberal dominance and advocating for voices of the developing world. If Francis were to articulate policies on global governance, they would likely involve democratizing institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and WTO, holding multinational corporations to higher standards, and championing a multilateral world where no single bloc dictates the rules.

Reforming Global Financial Institutions (IMF & World Bank): As noted earlier, Francis believes poorer nations deserve a greater say in institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank reuters.com. He is critical of one-size-fits-all policies (such as harsh austerity or structural adjustment programs) that these institutions imposed in the past, which often hurt the poor. A Franciscan policy agenda would push the IMF/World Bank to shift from a sole focus on financial stability and growth toward human development metrics. For example, loan programs would be evaluated on how well they reduce poverty and inequality, not just on fiscal targets. He would likely encourage these institutions to support debt forgiveness, as we discussed, and to offer grants or low-interest loans for education, health, and environmental protection, without heavy conditionalities that infringe on a country’s ability to care for its people.

Francis might also support new governance arrangements: increasing the voting power of African and Latin American countries at the IMF, or creating additional regional development banks that operate on solidarity principles (much as the Church has its own development agencies). His overall stance is that global finance should operate “on behalf of the peoples’ development and not vice versa”. This echoes similar calls by economists like Stiglitz who have argued the Bretton Woods institutions need democratization and a mandate refocus.

World Trade Organization (WTO) and Trade Rules: For the WTO, Francis would aim for rules that are fair to developing countries. This could mean supporting waivers (as he did for COVID vaccine patents, implicitly) so poorer countries can access technology and goods in crises. He’d advocate that trade agreements incorporate labor and environmental standards. He might back the idea of “trade justice tribunals” where poorer nations can challenge unfair trade practices by big powers. Given his emphasis on food security, he could support allowing countries to protect small farmers from sudden import surges. In essence, he’d push the WTO to bend its free trade ethos when necessary to uphold human rights, food security, and sustainable development.

United Nations and Global Cooperation: Pope Francis is a strong proponent of the United Nations as a forum for addressing global problems, but he wants it to be more effective. He has expressed support for the concept of world authority guided by law to deal with issues like peace and environment vaticannews.va. This ties into his multipolar vision: “The Pope’s vision is a multipolar one, a multilateral one, insisting on… multiparty agreements among states” vaticannews.va. So he would endorse strengthening multilateral treaties – whether on climate (Paris Agreement), arms control, or others – and ensuring broad participation. His mention of reviving the “spirit of Helsinki” (the 1975 accords that improved East-West relations) shows he favors dialogue and inclusive diplomacy over cold-war style blocs vaticannews.va. Thus, in geopolitics, he’s aligned with those who argue for a multiplex world with many actors (states, NGOs, peoples’ movements) contributing, rather than a unipolar or strictly bipolar world.

Stance Toward U.S.-Led Neoliberalism: While Pope Francis did not directly antagonized countries, his critique of neoliberal capitalism often serves as a critique of the economic model historically championed by the U.S. and Western-led institutions. He does not side with any rival power; instead, he charts a course that often aligns with the concerns of the Global South. For instance, he has condemned international arms trade fueling conflicts (implicitly critiquing major arms exporters like the U.S., Russia, etc.), and he opposed the Iraq War and other interventions. On the economic front, his disapproval of “trickle-down” economics and “the dictatorship of an impersonal economy” vatican.va vatican.va is a rejection of the market fundamentalism that underpinned the Washington Consensus. In that sense, Francis’s policies would diverge from the neoliberal playbook: he’d replace austerity with investment in the poor, deregulation with regulation for the common good, and privatization with protection of public goods. This puts him intellectually in line with many center-left and heterodox economists globally, and also with movements in the Global South that seek greater economic autonomy and social justice (like “Buen Vivir” in Latin America or calls for a New International Economic Order).

Engagement with China and Other Powers: Francis has also shown a willingness to engage with all global powers, including those outside the Western orbit. He struck a provisional agreement with China on the appointment of bishops – controversial to some, but indicative of his diplomatic approach of dialogue even with rivals. In an economic sense, he might welcome China’s investments in poorer countries if they truly help development, but he would equally criticize any neo-colonial aspects (debt traps, exploitation) as he would Western ones. Essentially, Francis doesn’t take sides in power politics; he takes the side of the poor and the planet. So whether dealing with the U.S., EU, China, or others, he would advocate prioritizing human dignity over geopolitical advantage. For example, he urged richer countries to share COVID-19 vaccines with poorer ones, lamenting the nationalism that saw wealthy nations hoard doses while the global South waited – a clear call for solidarity over profit or national interest.

Role of Civil Society and “Multilateralism from Below”: A unique feature of Francis’s outlook is the importance of grassroots movements. He has convened “World Meetings of Popular Movements” multiple times, bringing together labor unions, indigenous groups, landless farmers, etc. He believes change must also come “from below”, not only from state elites vaticannews.va. In the context of global institutions, he cites how civil society achieved the Landmine Ban Treaty (the Ottawa Process) as an example of bottom-up multilateral success where governments lagged vaticannews.va. Thus, his policy orientation would encourage significant participation of NGOs, religious groups, and community representatives in international deliberations – a democratization of globalization. He might support something like a “People’s Assembly” adjunct to the UN, or formal consultative roles for civil society in the IMF/WTO processes, to inject the experiences of those usually excluded.

Holding Multinational Corporations Accountable: We’ve touched on this under trade, but to emphasize: Francis often speaks of the “empire of money” and how unchecked corporate power can harm the vulnerable vatican.va. He would push for international frameworks where corporations are subordinate to the common good. This includes fighting corruption (companies exploiting weak governance through bribes – he’s spoken against corruption in both public and private spheres) and ensuring companies respect labor and environment standards abroad as if they were at home. His mention that some companies do in poor countries what they’d never dare do back home vatican.va suggests he’d approve of laws that extend home-country jurisdiction over corporate abuses (so a corporation from country X can be sued in country X for violations in country Y). Europe is debating due diligence laws of this kind – Francis would likely endorse them and call for them globally.

Finally, Geopolitical Orientation – Global South Solidarity: Francis has metaphorically shifted the Catholic Church’s “center of gravity” towards the peripheries. He frequently visits slums, refugee camps, and war-torn areas to show solidarity. As a policy-maker, his geopolitical stance would strongly favor peaceful resolution of conflicts (he’s mediated between countries like Cuba/U.S. and helped South Sudan’s leaders reconcile) and addressing global issues through cooperation rather than competition. He views phenomena like inequality, climate change, migration, and health pandemics as global commons problems requiring united action. His frequent refrain is that “no one is saved alone… we’re all in the same boat.” This leads to support for multipolarity in the sense that all regions have a voice, and multipartner solutions – e.g., involving not just the G7 but also the G20 and beyond, including the African Union, CELAC, ASEAN, etc., in shaping economic policies.

In essence, Pope Francis would seek to “reconfigure and recreate” the multilateral system for today’s world vaticannews.va vaticannews.va. He’d infuse it with the values of solidarity, equity, and care for creation. Whether reforming existing institutions or building new ones, his goal is a world order where economic policies and geopolitics alike are oriented toward “eliminating hunger and poverty and defending fundamental human rights” vaticannews.va. This is both a radical and profoundly ethical orientation – one that challenges both East and West, North and South, to transcend narrow interests and work truly as a single human family.

Final Reflection: The Prophet Economist

Pope Francis does not write policy briefs—but if he did, they would rival those of the most visionary economists of our time. His analysis is not merely pastoral. It is precise, radical, and actionable. He envisions an economy that stops worshipping growth and starts building dignity, sustainability, and peace.

In a global system obsessed with efficiency, Francis asks a different question: “Does it serve life?”

The answer—if implemented—could redefine the 21st century.

🔽 Click to Expand: Final Remarks

Pope Francis’s economic and geopolitical vision, if translated into policy, would mark a significant shift toward an ethic of solidarity in global affairs. It is a vision deeply informed by the struggles of the poor and the cry of the earth – a “preferential option for the poor” writ large in macroeconomic decisions and international relations. In practical terms, Francisconomics would mean high inequality is tackled head-on through redistribution and just wages; markets are kept in check by the common good and strong social safety nets; trade and finance are reformed to uplift developing nations and not trap them; and climate action is pursued with urgency and fairness. It would also mean welcoming migrants as brothers and sisters, and democratizing global governance so that all nations and peoples have a seat at the table, not just the powerful few.

This approach aligns with many contemporary progressive economic thinkers and movements, demonstrating a rare harmony between spiritual values and advanced policy thinking. Thomas Piketty’s data and Francis’s moral voice both demand we address wealth concentration vatican.va theologicalstudies.net. Amartya Sen’s development-as-freedom finds resonance in Francis’s call for integral human development that “leaves no one behind.” Mariana Mazzucato’s entrepreneurial state is reflected in Francis’s insistence that political authority has not just the right but the duty to guide markets toward social goals vatican.va vatican.va. In a world grappling with inequality, pandemics, climate change, and displacement, Pope Francis offers a fundamentally humanistic and hopeful blueprint: an economy that hears both “the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor” vatican.va, and a geopolitics that favors “bridges over walls” and cooperation over domination.

Realizing this vision would require determined action: taxing extreme wealth, forgiving debts, investing massively in green jobs and poor communities, empowering workers, regulating global capital, and strengthening international solidarity at every level. It is a tall order, and Francis, ever the pastor, knows it appeals to the conscience as much as to the intellect. He does not provide technical fixes so much as he provides a moral compass. But as this report has shown, the compass aligns well with many concrete policy ideas espoused by forward-thinking economists. The message is that economics and politics are not value-neutral – they are instruments that can either include or exclude, kill or give life. Pope Francis, if an economist, would undoubtedly choose the path that gives life: an economy of inclusion, justice, and fraternity. As he wrote in Fratelli Tutti: “Good economics, true economics, has a moral ethos: it serves the common good and does not neglect the weakest”. It is precisely such good economics and moral ethos that his likely policies would strive to achieve vatican.va vatican.va.

“Human dignity must be at the center of every economic decision.” — Pope Francis

Sources and References:

Papal Encyclicals and Official Messages

- Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis, 2013

- Laudato Si’, Pope Francis, 2015

- Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis, 2020

- Laudate Deum, Pope Francis, 2023

- Message to World Bank and IMF, Pope Francis, 2021

- Speech to Popular Movements (Santa Cruz), Pope Francis, 2015

- Amazon Synod Opening Remarks, Pope Francis, 2019

- Angelus on Lampedusa, Pope Francis, 2013

Academic and Economic Frameworks

- Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty, 2013

- Development as Freedom, Amartya Sen, 1999

- Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism, Mariana Mazzucato, 2021

- Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth, 2017

- Globalization and Its Discontents, Joseph Stiglitz, 2002

Reports and Institutional Analysis

- World Inequality Report, World Inequality Lab, 2022

- Climate Inequality Report, Oxfam & Stockholm Environment Institute, 2023

- Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery, UNDP / IMF / HBS, 2022

- Financing for Sustainable Development Report, United Nations IATF, 2021

- Global Compact on Migration, United Nations, 2018

- Economic Policy for Full Employment and Climate Stabilization, Levy Economics Institute, 2022

- Time for Social Protection, ILO & UNDP, 2021

- Debt-for-Climate Swaps in the Caribbean, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2021

Journalism and Commentary

- Pope Francis Calls for Universal Basic Wage, The Guardian, 2020

- Pope Criticizes Wealth Inequality During COVID, Reuters, 2020

- Oxfam: Billionaires Emit More CO₂ Than Half of Humanity, Oxfam, 2023

- Pope Warns of Ecological Debt, Vatican News, 2015–2023