Did you know? Venezuela’s oil became a geopolitical “payment rail”

In the last decade, Venezuela’s state oil system (PDVSA) has been operating through multiple, distinct channels that moved value outward: oil-backed debt repayment, prepayments linked to future supply, subsidized shipments, swap contracts for diluents and fuels, and sanctions-era routing via gold and new intermediaries. (Reuters)

A core feature of the China–Venezuela relationship has been large state-backed financing tied to Venezuela’s oil flows. Carnegie reports China provided Venezuela over $60 billion in oil-backed loans over roughly a decade. (Carnegie Endowment)

Reuters reported Venezuela negotiated a grace period on about $19 billion in loans to Chinese banks “paid off with oil shipments.” (Reuters) Reuters also published background on China’s oil trade/investment with Venezuela and notes the same 2020 grace-period episode in that context. (Reuters)

AidData’s project-level documentation describes specific oil-collateral features (e.g., borrowing collateralized with PDVSA income from daily oil sales deposited into an escrow/collection account at China Development Bank). (China Global Development Dashboard) Inter-American Dialogue reporting likewise describes Chinese lending structures where repayment occurs through oil shipments. (The Dialogue)

Find out more below:

- “Over $60B in oil-backed loans” (Carnegie). (Carnegie Endowment)

- “~$19B… loans… paid off with oil shipments” (Reuters, 2020). (Reuters)

- Oil-collateral mechanics (AidData project documentation). (China Global Development Dashboard)

- Repayment-through-oil-shipment framing (Inter-American Dialogue). (The Dialogue)

Reuters reported Rosneft said it had made around $6 billion in pre-payments to Venezuela’s state oil company PDVSA. (Reuters) A Reuters special report further describes Russia/Rosneft using lending and credit lines to deepen its positioning in Venezuela’s oil sector, and provides Reuters calculations for total loans/credit lines over time. (Reuters)

Find out more below:

- Rosneft: “around $6B in pre-payments to PDVSA” (Reuters, 2017). (Reuters)

- Russia/Rosneft loans/credit-line positioning in Venezuela’s oil assets (Reuters Special Report). (Reuters)

Reuters reviewed internal PDVSA documents showing PDVSA purchased foreign crude for delivery to Cuba and that “OPEC member Venezuela bought $440 million in foreign crude” in that period for subsidized shipments to Cuba, describing favorable terms and the burden this imposed amid shortages at home. (Reuters) Reuters also reports the arrangement sits within a long-running exchange framework where Venezuela accepts goods and services from Cuba in return for oil under a pact signed in 2000. (Reuters)

Find out more below:

- “Bought $440M in foreign crude… for subsidized shipments to Cuba” (Reuters; PDVSA documents). (Reuters)

- Reuters detail on terms, pricing comparison, and goods/services exchange context (Reuters). (Reuters)

Reuters reported Iran delivered ~4.8 million barrels of condensate to PDVSA and joint ventures in 2021 (and also supplied gasoline) and “received in return at least 5.8 million barrels of Venezuela’s Merey 16 heavy crude and jet fuel.” (Reuters)

The U.S. Energy Information Administration describes that, in 2021, Iran began exporting condensates to Venezuela under a swap agreement, and notes those condensates act as a diluent for Venezuela’s extra-heavy crude. (U.S. Energy Information Administration) Reuters reporting in 2025 also characterizes a swap agreement allowing PDVSA to import crude/condensate between 2021 and 2023 for diluent use. (Reuters) Reuters reporting in 2024 describes the later deterioration/repair attempts of this oil-for-oil alliance and references PDVSA documents in that context. (Reuters)

Find out more below:

- 2021 cargo totals: 4.8M bbl condensate → PDVSA; ≥5.8M bbl heavy crude/jet fuel → Iran (Reuters). (Reuters)

- Swap agreement described; condensate as diluent (EIA). (U.S. Energy Information Administration)

- Swap period and diluent function (Reuters, 2025). (Reuters)

- PDVSA documents referenced in 2024 alliance/friction reporting (Reuters, 2024). (Reuters)

Reuters reported Venezuela exported $779 million of gold to Turkey in 2018, citing Turkish government statistics. (Reuters) Reuters also reported Venezuela’s mining minister said the gold was refined in Turkey and then returned to Venezuela to become part of the central bank’s portfolio of assets. (Reuters)

Separately, Reuters reported that a Turkey-registered firm (Iveex) loaded Venezuelan crude and products in April 2019, citing PDVSA documents; Reuters quantified those April cargoes as equivalent to just under 8% of Venezuela’s exports for that month. (Reuters)

Find out more below:

- $779M in gold exports to Turkey in 2018 (Reuters citing Turkish statistics). (Reuters)

- Gold refining in Turkey and return as central bank assets (Reuters). (Reuters)

- Turkey-registered Iveex buying/loading Venezuelan crude/products per PDVSA documents; April 2019 share (Reuters). (Reuters)

Maintaining the status-quo

These channels operate through state decisions and state-linked execution: Reuters’ China grace-period story is explicitly about Venezuela’s government negotiating terms with Chinese banks. (Reuters) Reuters’ Cuba reporting frames the Cuba shipments as PDVSA purchases and shipments under the Maduro government period, based on internal documents reviewed by Reuters. (Reuters)

Across China loans, Rosneft prepayments, Cuba supply, Iran swaps, and Turkey-linked gold/oil channels, Reuters, EIA, and major analytical sources document Venezuela’s oil functioning not only as export revenue, but as a settlement mechanism for credit, swaps, and political-economic support. (Reuters)

🔽 Click to Expand: Why it matters — Economic impact

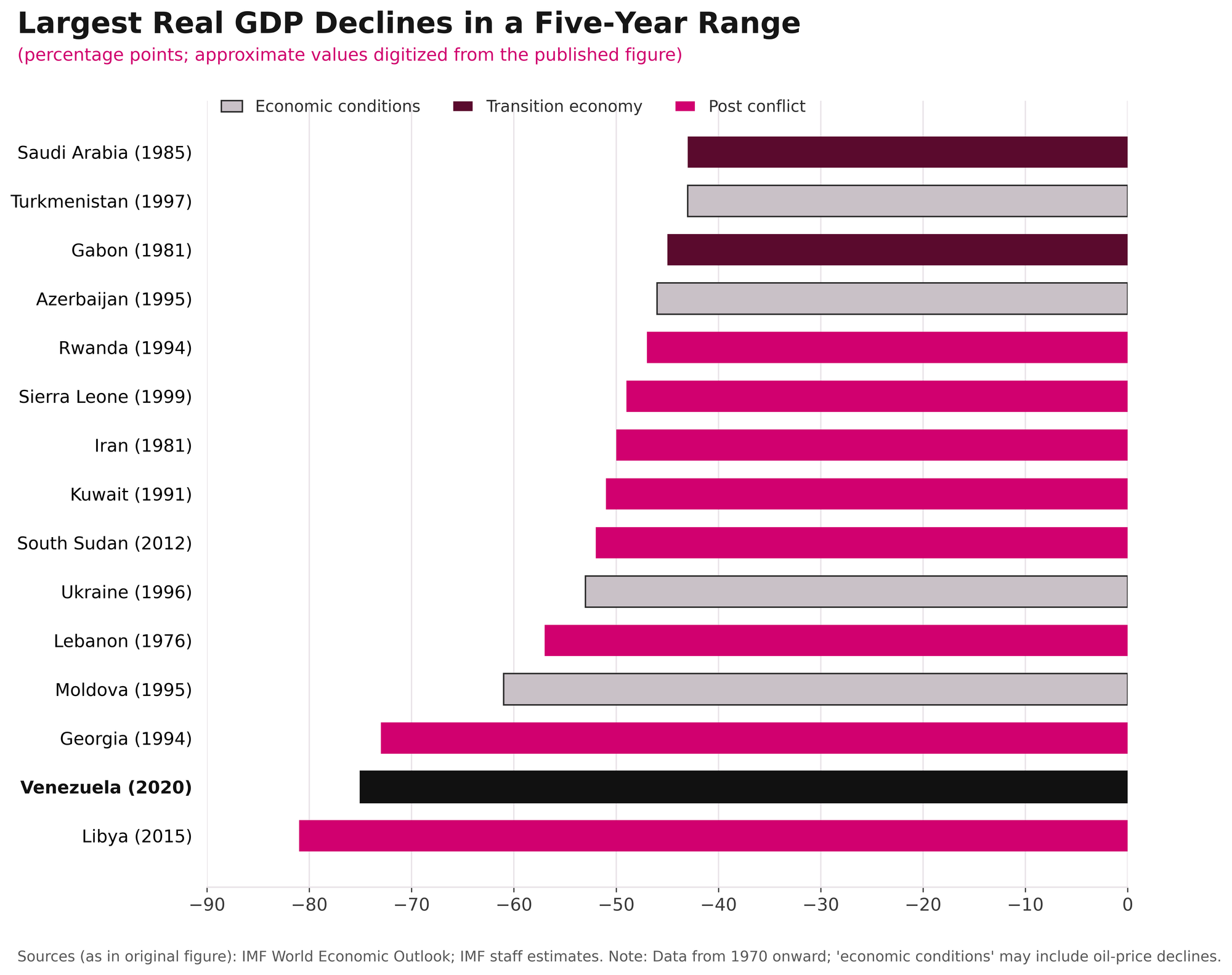

The IMF describes Venezuela’s last decade as an economic collapse on the scale of a wartime contraction: real GDP contracted by more than 75% between 2013 and 2021. In the same IMF report, the collapse is linked to large fiscal deficits, hyperinflation, currency depreciation, and a debt crisis.

A key driver was the implosion of the oil engine itself: the IMF reports crude production averaged 2.8 mbpd (2008–13), fell to 0.9 mbpd (2019), and bottomed near 0.4 mbpd (mid-2020)—and it explicitly notes the sharp decline preceded U.S. oil sanctions introduced in January 2019. With less oil produced, the rest of the economy also broke down: the IMF cites Central Bank of Venezuela data showing non-oil GDP fell ~56% between 2013Q1 and 2019Q1, with construction collapsing 96% and major contractions in manufacturing and financial services.

This matters for the “oil relationships” story because, in a collapse like this, oil stops being just export revenue and becomes a financing and survival tool—a way to keep the system going when normal financing is gone. The IMF explains that hyperinflation rose as massive fiscal deficits (averaging 16.8% of GDP between 2014 and 2019) were monetized, because other financing sources (including oil and tax revenue) were collapsing. The IMF also reports that despite being an oil producer, Venezuela experienced widespread fuel shortages, disrupting mobility and significantly increasing transportation costs, and that gasoline shortages and infrastructure breakdown contributed to a broader internal economic fragmentation.

Against that backdrop, the documented external channels had two very concrete “impact” implications:

- They shaped how many barrels produced real cash vs. serviced obligations or swaps. Reuters reports Venezuela negotiated a grace period on about $19 billion in loans to Chinese banks that were paid off with oil shipments—meaning part of Venezuela’s oil flow functioned like a debt payment stream, not a normal cash sale. (Reuters)

- They affected shortages and export capability through specific inputs and trade-offs. Reuters reports PDVSA bought nearly $440 million of foreign crude and shipped it to Cuba on friendly credit terms, often at a loss—an explicit example of scarce resources being used for an external commitment while Venezuelans faced hardship. (Reuters) Reuters also documents swap-style cooperation with Iran in 2021: ~4.8 million barrels of condensate delivered to PDVSA/joint ventures (plus gasoline), and at least 5.8 million barrels of Venezuelan heavy crude and jet fuel received in return—condensate that helps Venezuela blend and move very heavy crude. (Reuters)

Finally, the IMF adds a critical detail about “how exports worked under pressure”: it says Venezuela placed heavy crude in Asian markets at a substantial price discount, which alleviated in part the impact of sanctions, and notes the current account recorded surpluses since 2017 (except 2020).

Bottom line: in an economy that the IMF describes as collapsing by >75% with oil production falling to historic lows, these oil-linked arrangements matter because they determine whether Venezuela’s limited oil output is converted into cash, debt service, imported inputs (like condensate), or subsidized external support—and each choice has visible consequences in inflation, shortages, and the ability to keep exporting. (Reuters)