China’s Long Squeeze: Demography, Food Security, and the Resilience State

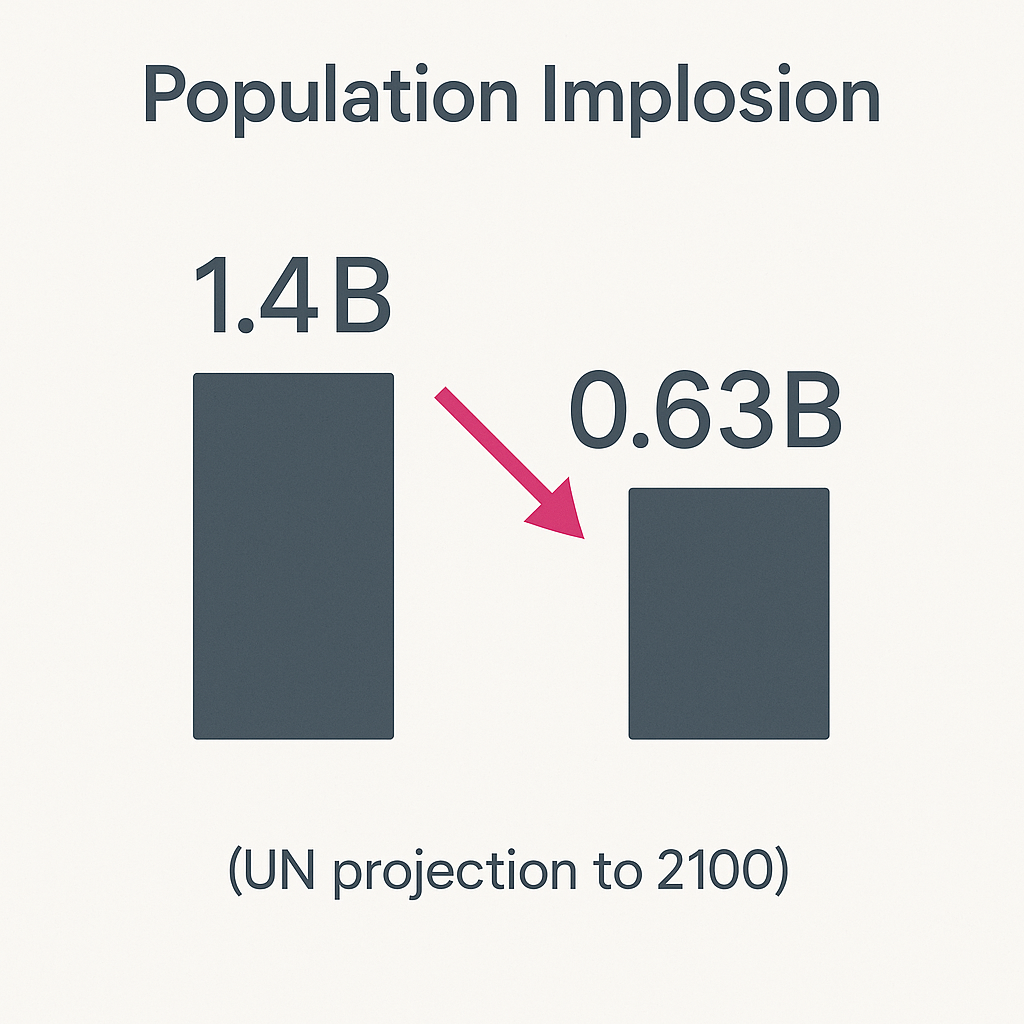

By 2100, China is expected to shrink from 1.4 billion to roughly 633 million people – the largest absolute population loss of any country on earth, according to the UN.

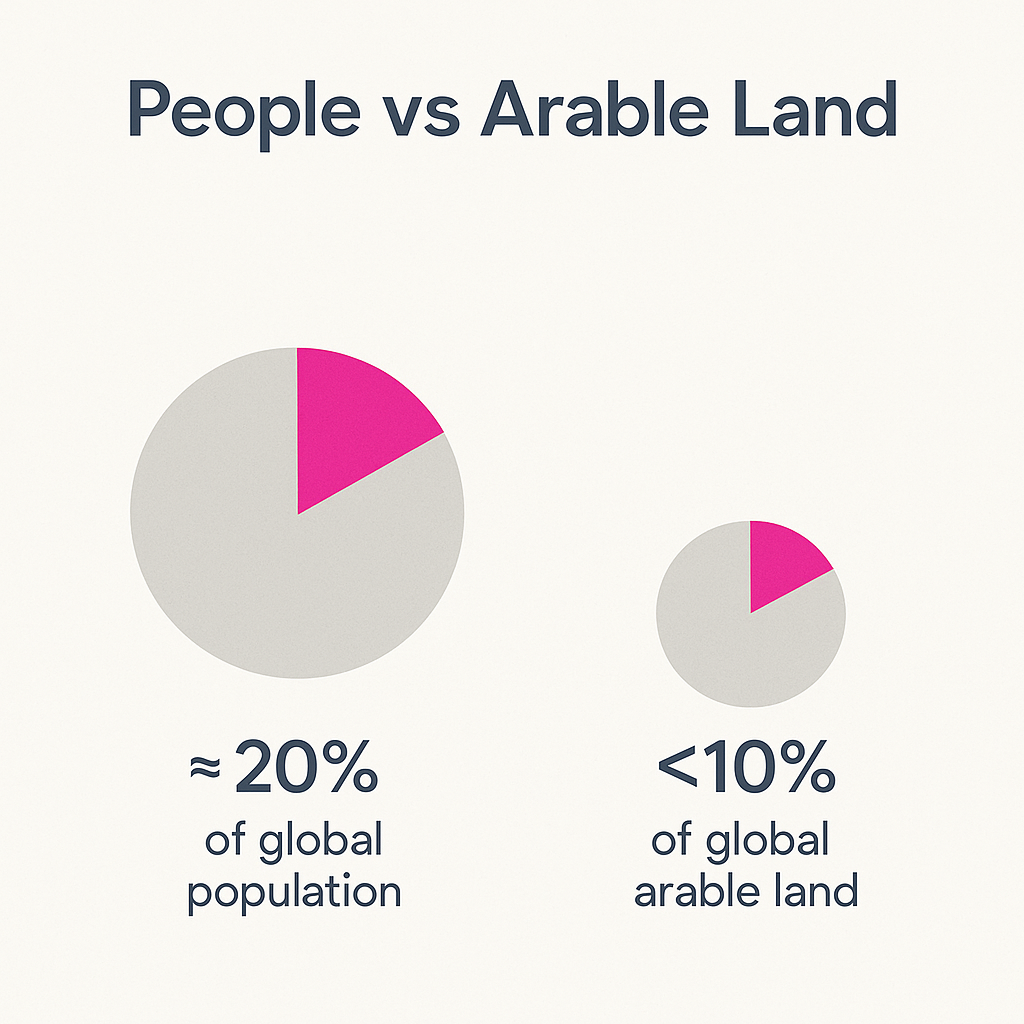

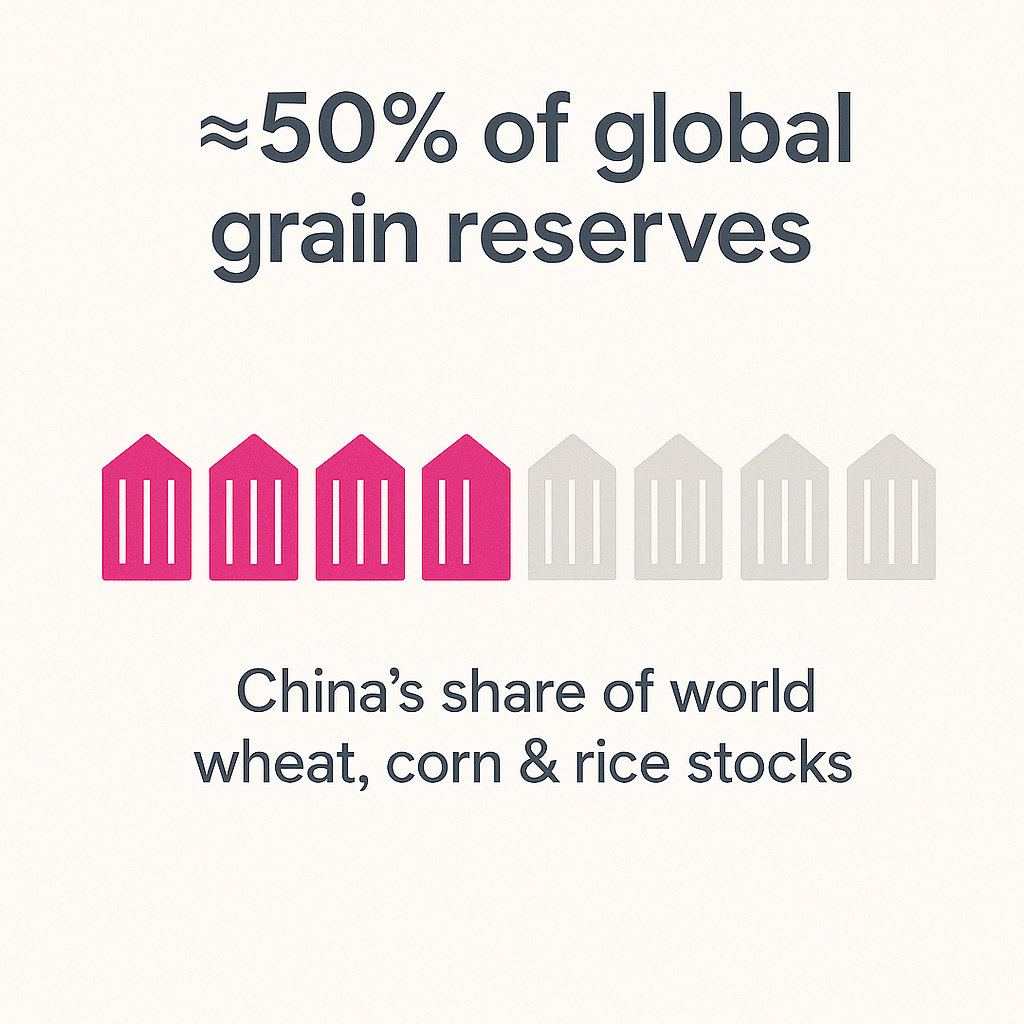

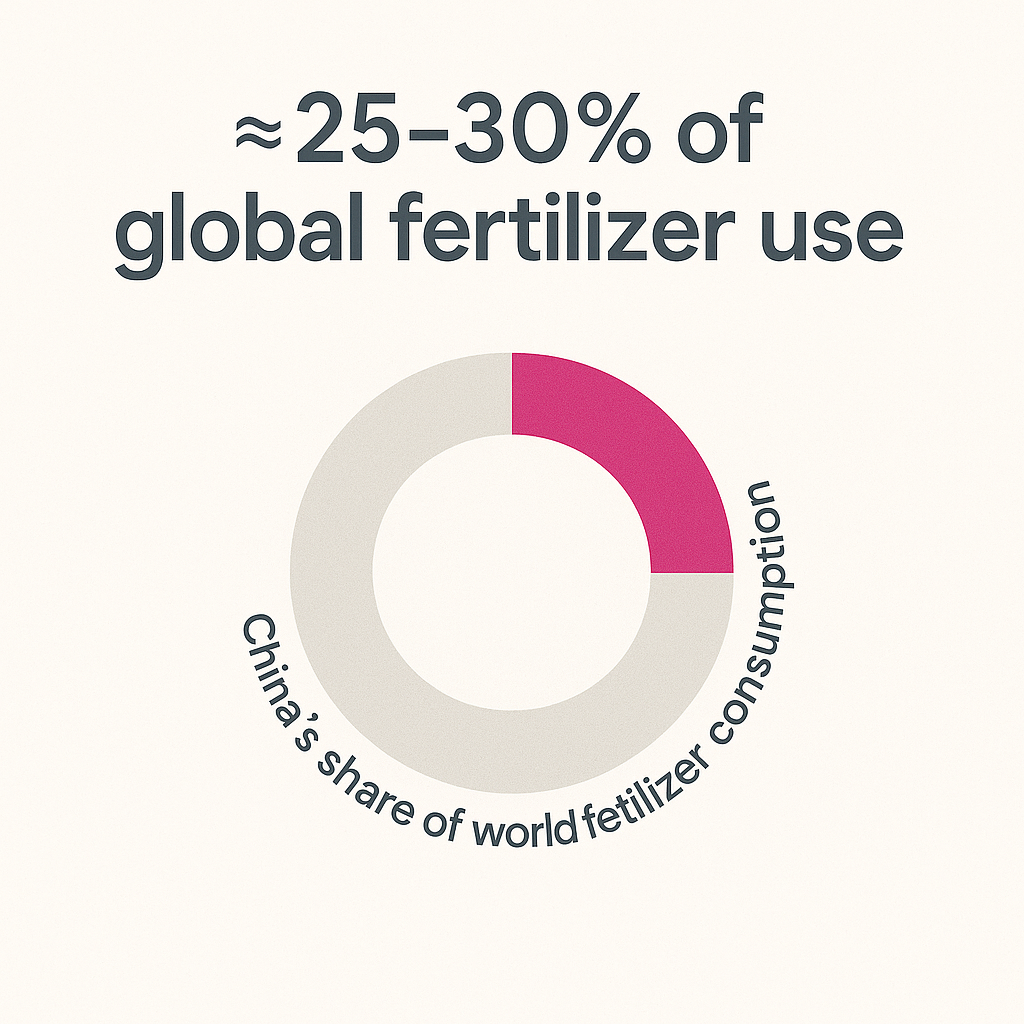

By 2100, China is expected to shrink from 1.4 billion to roughly 633 million people – the largest absolute population loss of any country on earth, according to the UN. At the same time, it is trying to feed one-fifth of humanity on less than a tenth of the world’s arable land, while sitting on about half of the world’s grain reserves and a quarter of its fertilizer use.

Executive Summary

China enters the mid-21st century with two hard constraints that no narrative can wish away: a fast-shrinking, rapidly ageing population and a resource base—land, water, and imported inputs—that must carry the weight of feeding ~1.4 billion people with under 10% of the world’s arable land.

UN population projections now show China’s population roughly halving by 2100, from about 1.4 billion at its 2022 peak to around 630–640 million.(UN Population Division) The demographic “boom” is over; the long squeeze has begun.

On the food side, Beijing has locked in a “red line” of 120 million hectares of arable land and is racing to upgrade over 66.7 million hectares to “high-standard farmland” with better irrigation, soil management, and mechanization.(State Council of China) At the same time, the North China Plain—the country’s breadbasket—is living on borrowed groundwater, with aquifers depleting at unsustainable rates and per-capita water availability in some northern regions far below international scarcity thresholds.(Baker Institute)

China is not on the verge of a sudden famine or system collapse. Grain output has stayed above 650 million tonnes for years, and new technologies—high-standard farmland, improved seeds, GM and gene-edited crops, and expanding agricultural insurance—are all being deployed to stabilise the system.(China Daily)

But it is moving into a tighter, more brittle equilibrium:

- Demographically, fewer workers must support more elderly citizens, while urban households face rising living costs and weak fertility incentives.

- Structurally, food security depends on a combination of imported inputs (especially potash), stressed domestic water resources, and highly managed supply chains.

- Politically, Beijing is building what we can call a “Resilience State”: heavy use of insurance, reserves, technology, and strategic trade to manage chronic stress rather than eliminate it.

This white paper lays out a framework for thinking about that long squeeze, and what it implies for China’s policy choices and for the rest of the world.

How does a great power manage decades of demographic decline, resource stress, and input dependence without triggering internal crisis or external vulnerability?

We frame the problem in five linked systems:

- Demographic downshift – shrinking working-age population, rising dependency ratios, and the implications for growth and fiscal capacity.

- Food system under stress – land quality, soil and water constraints, and climate volatility.

- Input & supply-chain security – nitrogen, phosphate, potash, energy, and critical logistics.

- Protein security after African Swine Fever (ASF) – restructuring of the pork sector and feed dependence.

- The Resilience State – insurance, technology, reserves, and trade as tools to manage a permanent squeeze.

Key findings:

- China’s population is on a path to shrink by roughly half by 2100, with a worker-to-retiree ratio that will erode fiscal space for everything from food subsidies to climate adaptation.(UN Population Division)

- Food security is less about total hectares and more about water and soil: the North China Plain remains water-scarce and groundwater-dependent, even as high-standard farmland expands.(Baker Institute)

- Potash is the critical external choke point; China is largely self-reliant in nitrogen and a major producer of phosphate, but potash imports remain strategically exposed.(Radio Free Asia)

- ASF forced a painful clean-up and consolidation of the pork sector, revealing both the vulnerability of intensive livestock systems and the state’s willingness to tolerate short-term pain for long-term restructuring.(Economic Research Service)

- China is deliberately building a resilience toolkit: record-scale agricultural insurance, massive investment in high-standard farmland, and a rapid push into GM/gene-edited crops to raise yields and reduce input risk.(Gov.cn)

The story is, therefore, less “sudden collapse” and more “managed squeeze under hard constraints.”

The peak is behind, the drag is ahead

UN World Population Prospects 2024 confirms that China’s population peaked around 1.4 billion in the early 2020s and has already begun to shrink.(UN Population Division)

Pew Research, summarising the UN projections, estimates that China’s population could fall to roughly 633 million by 2100—a decline of more than 50%.(Pew Research Center) Recent reporting by The Washington Post underscores the speed of ageing: fertility has dropped close to one child per woman, while the median age has climbed above 39.(The Washington Post)

Even if policy succeeded in nudging fertility modestly higher, the age structure is already locked in. The 2030s and 2040s are thus defined by:

- A shrinking labour force.

- A growing elderly population needing pensions, health care, and long-term care.

- Slower headline growth unless productivity rises sharply.

Dependency economics

For food and climate resilience, what matters is not just the number of mouths, but who is working and where fiscal capacity goes:

- Fewer workers per retiree means higher pension and health burdens, potentially crowding out environmental and adaptation spending.

- Urbanisation continues, so more people are urban consumers rather than rural producers.

- The state faces a choice between:

- Keeping food cheap via subsidies and price controls, or

- Allowing higher food prices to transmit resource scarcity but risking social discontent.

Our baseline assumption is that Beijing will prioritize political stability and food price stability, even at the cost of other spending—especially in downturns.

Land and soil: red lines and new baselines

China’s leadership repeatedly emphasises that the country must maintain at least 1.8 billion mu (120 million hectares) of arable land—the famous “red line”—as the non-negotiable baseline for food security.(FAOHome)

Alongside the red line, Beijing is upgrading land quality:

- Over 66.7 million hectares of high-standard farmland have been built by the end of 2023, with better irrigation, soil management, and resistance to droughts and floods.(Xinhua News)

- High-standard farmland now accounts for a large share of grain output and cash crops; mechanization exceeds 75% of major farming operations.(Gov.cn)

This is the opposite of a system “doing nothing” about land degradation; it is actively engineering its way to a more controlled, high-input equilibrium.

Water and groundwater: the invisible constraint

Where the picture is much tougher is water.

The North China Plain, the country’s main grain belt, is classified as severely water-stressed; long-term studies show groundwater tables dropping and water quality deteriorating under the pressure of irrigated double-cropping (winter wheat and summer maize).(Baker Institute)

Estimates for per-capita freshwater availability in some northern regions are well below 500 m³/year, significantly under the UN’s “water scarcity” threshold and far below global averages.(Almendron)

China is trying to adapt by:

- Expanding irrigated farmland and improving irrigation efficiency (less water per mu, higher yield per cubic metre).(Xinhua News)

- Promoting alternative cropping systems and agronomic practices to reduce groundwater extraction.(MDPI)

But the basic reality remains: China’s food security is fundamentally constrained by water, not just land. Drought shocks in the North China Plain could create large import needs; one scenario from the Baker Institute suggests that a 33% crop loss in the region could force China to absorb around 20% of globally tradable corn and 13% of tradable wheat in a single year—enough to shake world markets.(Baker Institute)

Climate volatility

Climate change layers further risk on top of stressed systems. IPCC assessments and regional studies point to:

- Higher frequency of heatwaves and droughts in northern China.

- More intense rainfall events and flood risks in some river basins.

- Increased uncertainty around yields for water-intensive staples.

China’s response—high-standard farmland, new seed varieties, and risk-sharing instruments—is best read as a climate adaptation strategy, even when it is branded as “grain security.”

China’s fertilizer story can be simplified to:

- Nitrogen (N) – Largely domestic, but energy-intensive.

- Phosphate (P) – Strong domestic base; China is a major producer and exporter.

- Potash (K) – The critical import-dependent vulnerability.

Nitrogen and energy

China produces most of its nitrogen fertilizer at home, using natural gas and coal as feedstocks for ammonia. The vulnerabilities here are less about physical access and more about:

- Energy costs and emissions (coal-based ammonia is carbon-intensive).

- Exposure to policy pressures—domestic environmental regulations, and external scrutiny via mechanisms like the EU’s CBAM, which will increasingly look at fertilizer carbon footprints.(Kelewell Trading)

Phosphate: a relative strength

On phosphorus, China is in a comparatively strong position:

- It is one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of phosphate fertilizers.

- In tight markets, Beijing has already used export controls (for example in 2021–2022) to prioritise domestic availability.

From a resilience perspective, phosphate is a lever China can pull—not a lever others can easily pull against China.

Potash: the external choke point

Potash is different. China has limited domestic reserves and relies heavily on imports from a small set of suppliers—traditionally Canada, Russia, Belarus, and increasingly Laos.(Radio Free Asia)

Recent analyses suggest:

- Potash accounts for more than four-fifths of China’s fertilizer imports by value, leaving the sector exposed to shipping disruptions or sanctions.(Radio Free Asia)

- China has been actively diversifying supply, financing new potash projects in Laos and deepening ties with Russia and Belarus.(Radio Free Asia)

In a geopolitical crisis that severed access from Western producers (Canada, the US, Israel, Jordan), potash would be the first real pinch point. That does not mean an immediate food collapse—but it would raise fertilizer prices, complicate yield maintenance, and force sharper trade-offs between domestic agricultural support and other priorities.

The shock

African Swine Fever (ASF) hit China’s pork sector between 2018–2020 and triggered one of the largest livestock shocks in modern history:

- Estimates suggest around 40% of China’s pig herd was lost through disease and culling.(nature.com)

- Pork output fell sharply; one USDA study estimates a loss of about 27.9 million tonnes of pork over a 30-month cycle.(Economic Research Service)

- Official statistics recorded a 27.5% decline in the herd by end-2019, and slaughter numbers fell more than 20%.(Reuters)

Pork prices more than doubled, with knock-on effects on food inflation and household budgets.(Economic Research Service)

The response: consolidation and industrialisation

China’s response was not to abandon intensive pork production, but to rebuild it in a more corporate, biosecure form:

- Encouraging large, vertically integrated producers with better biosecurity.

- Supporting restocking through subsidies and credit.

- Increasing feed grain and oilseed imports (corn and soy) to stabilise supply.

In economic terms, ASF accelerated a shift from backyard and small-scale farms to industrial operations, which are more efficient but also more tightly coupled to global feed markets.

Persistent vulnerability

The lesson of ASF is important for the broader “long squeeze” theme:

- China’s protein system is now more integrated, more efficient, but also more complex and more dependent on imported feed and sophisticated logistics.

- A disease shock, trade war, or logistics disruption can translate quickly from sectoral stress into a broader food-price shock.

This is one reason Beijing puts such emphasis on feed self-sufficiency, GM corn and soybeans, and diversified import sources—they are central to protein security, not just crop yields.(Food Advertising System)

Instead of treating each risk in isolation, Beijing is increasingly building a system-level resilience toolkit.

Agricultural insurance as macro-stabiliser

Since pilot programs in 2007, agricultural insurance has scaled dramatically:

- By 2022, agricultural insurance premiums reached ~122 billion yuan, providing risk protection worth about 5.46 trillion yuan to 167 million rural households.(Gov.cn)

- Recent empirical studies suggest agricultural insurance has raised farm output by around 9%, by stabilising income expectations and enabling higher-productivity investments.(Insurance Asia)

This is not just a micro-product; it functions as a policy instrument:

- Spreading climate and disease risk across time and space.

- Reducing the need for ad-hoc bailouts after every shock.

- Giving Beijing a data-rich view of agricultural risk across regions and crops.

High-standard farmland and mechanization

We have already seen the scale: over 66.7 million hectares of high-standard farmland, irrigated land expansion, and mechanization above 75%.(Xinhua News)

Policy goals here are explicit:

- Buffer against climate volatility – fields engineered to withstand droughts and floods.

- Raise yield per hectare and per cubic metre of water – crucial under water constraints.

- Standardise production – enabling scale efficiencies and easier application of technology (sensors, precision agriculture, integrated water–fertilizer systems).

Biotechnology: GM and gene-edited crops

After years of caution, China is accelerating approvals for GM and gene-edited crops:

- Dozens of GM corn and soybean varieties have been approved for planting, with more varieties progressing through biosafety certification.(Food Advertising System)

- In 2024, China granted its first gene-edited wheat safety approval, alongside additional GM and gene-edited corn and soy varieties aimed at yield and disease resistance.(Reuters)

- GM corn plantings are being scaled up, with 2025 areas reportedly 4–5 times higher than 2024 pilot levels, though still only a small share of total corn acreage.(Reuters)

The strategic goals are clear:

- Higher yields per unit of land and water.

- Reduced pesticide and fertilizer needs for some traits.

- Less dependence on imported GM feed grain, by producing more at home.

Grain reserves and trade management

China maintains large state grain reserves and uses import diversification to manage exposure:

- Sourcing corn and soy from the US, Brazil, Argentina, and others; increasingly looking to the Black Sea, Southeast Asia, and domestic GM production to spread risk.

- Using export and import controls on fertilizers and grains when necessary to stabilise domestic prices.(CSIS)

In combination, insurance, technology, and state control over reserves and trade form a Resilience State architecture: not eliminating shocks, but absorbing and re-routing them.

Scenario A – “Managed Squeeze” (Baseline)

- Population falls modestly by 2035, more sharply by 2050, but labour shortages are partially offset by automation.

- High-standard farmland reaches the official targets; GM and gene-edited crops cover a substantial share of corn and soy acreage.

- Agricultural insurance and disaster management reduce the macro-impact of climate shocks, though local crises remain frequent.

- Potash dependence is mitigated but not eliminated; China continues to invest in supplier countries and logistics routes.

Result: No famine, but chronic pressure—food prices are politically sensitive, fiscal resources are continuously channelled into subsidies, technology, and rural support.

Scenario B – “Water Shock”

- A combination of droughts and groundwater depletion in the North China Plain triggers several years of below-trend harvests.

- China leans heavily on imports, temporarily absorbing a large share of global tradable wheat and corn.(Baker Institute)

- Global prices spike; lower-income importers in Africa and the Middle East face food-price crises.

- Domestically, Beijing tightens export controls, expands emergency support, and accelerates GM/water-efficient crop deployment.

Result: Food security is maintained at home, but at a cost to global food stability.

Scenario C – “Geopolitical Potash Crunch”

- A geopolitical crisis disrupts potash flows from Canada and other Western suppliers; Russia/Belarus supplies are also constrained.

- China still secures some volumes from Laos and friendly suppliers, but prices jump and rationing is needed.(Radio Free Asia)

- Short-term impact is on fertilizer costs and yields; medium-term response includes accelerated investment in alternative fertilizers, better nutrient management, and bargaining for resource access.

Result: Fertilizer becomes a strategic bargaining chip, reinforcing the perception of agriculture and inputs as part of national security.

When drought in the North China Plain can force imports equal to 20% of tradable global corn, and a single disease outbreak can erase nearly 28 million tonnes of pork, Chinese “domestic” food security is no longer a domestic story at all – it’s a global volatility machine.

Two shocks you think are ‘just in China’ – a regional drought and a pig disease – literally go into a machine and come out as global price waves.

For the rest of the world, China’s long squeeze has at least four implications:

- Volatility exporter

When domestic harvests or inputs fall short, China’s sheer scale can move global markets—especially for grains, soy, and potash. Small percentage shifts in Chinese imports translate into large swings in world prices. - Standard-setter in ag-tech and insurance

The scale of agricultural insurance and the speed of GM/gene-edited crop adoption mean China will increasingly shape global norms on biotech regulation, input markets, and climate risk pricing. - Climate adaptation race

China’s success or failure in adapting to water stress and climate volatility affects not only its own food security but the global carbon and land-use balance, via changing imports, land-use patterns abroad, and diplomatic initiatives in food corridors. - Geopolitics of inputs

Potash, phosphate, seeds, and ag-biotech IP join semiconductors and rare earths as strategic bargaining domains. Countries with significant fertilizer or seed technology may find themselves drawn into tighter political-economic relationships with Beijing.

- Demographic decline and resource constraints are real and severe.

- They do not automatically produce state collapse, famine, or political implosion.

Instead, they produce a long phase of managed squeeze:

- A state that channels more resources into resilience infrastructure—insurance, biotech, high-standard farmland, reserves, and risk management.

- A political economy that must juggle ageing, growth, and food price stability with limited fiscal space.

- A global system in which China’s shocks become everyone’s shocks, via trade and input markets.

For policy analysts, the right questions are therefore:

- How robust is China’s Resilience State to compound shocks—for example, a water crisis plus a potash supply shock?

- How will demographic pressure shape budget priorities between social security, military modernisation, and climate adaptation?

- And how can other countries design their own policies—on trade, climate, and food security—assuming not a Chinese collapse, but a large, ageing, and permanently stressed China that remains deeply integrated into global food and input markets?

Those are the questions the next stage of research should quantify—through scenario modelling, stress tests of global grain and fertilizer markets, and a closer look at how China’s internal insurance and adaptation systems reallocate risk across households, firms, and the state.