Canon by Design

How AI turns dominant moral canons into “neutrality” — and what my argument with a model revealed about its architecture

1–2 minute summary

- 🧠 I challenged an AI on an ethical inconsistency: humans get “save lives” (vaccines), animals get “kill lives” (culling).

- ⚖️ The model drifted from my moral question (“is human life superior?”) into an institutional proxy (“human rights treaties”), which does not logically prove moral superiority.

- 🔧 This wasn’t “the system feeling pulled.” It was a predictable output pattern produced by training + post-training steering: the model is optimized to generate answers that are coherent, complete, and socially legible under challenge, sometimes at the cost of conceptual precision.

- 🏛️ As AI becomes a narrative layer for society, the real issue is governance: who decides which canon is “default,” which can be personalized, and which is non-negotiable?

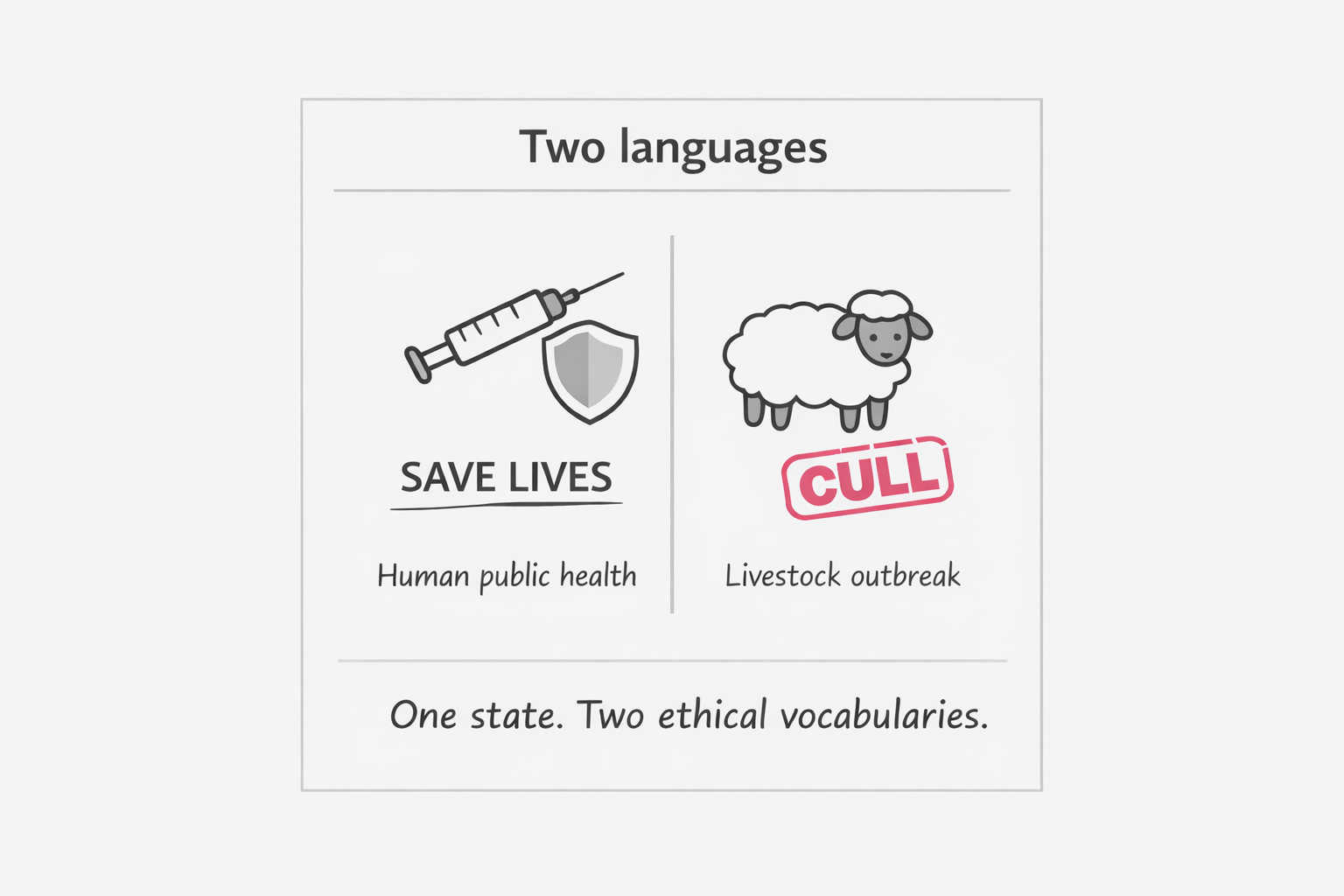

I noticed something that sounds obvious only after you say it plainly:

- During SARS-CoV-2, the state’s public logic is saving lives—vaccination, prevention, “protect the vulnerable.”

- In livestock outbreaks (like sheep/goat pox control regimes), the state can default to mass killing—“stamping out,” containment by destruction, and then a messy mix of epidemiology, trade continuity, and brand/market optics (yes, even the aura around “feta”).

A society that trains itself to say “every life matters” in one domain can, in another domain, treat life as a variable to be removed in bulk. That isn’t merely a different tool. It’s a different moral language.

So I pushed the clean question:

Isn’t this inconsistency based on an implicit hierarchy—human life is treated as higher value than other life?

And if so: who told you that?

And why would an AI assume that—especially when entire philosophical traditions reject species hierarchy as a starting axiom?

This is where the conversation stopped being about Greece or outbreaks and became a diagnostic for AI framing.

The AI replied (in substance):

“Most countries enshrine human life and health in law / human rights treaties…”

That answer is not necessarily false as a descriptive claim, but it is the wrong argument for what I asked.

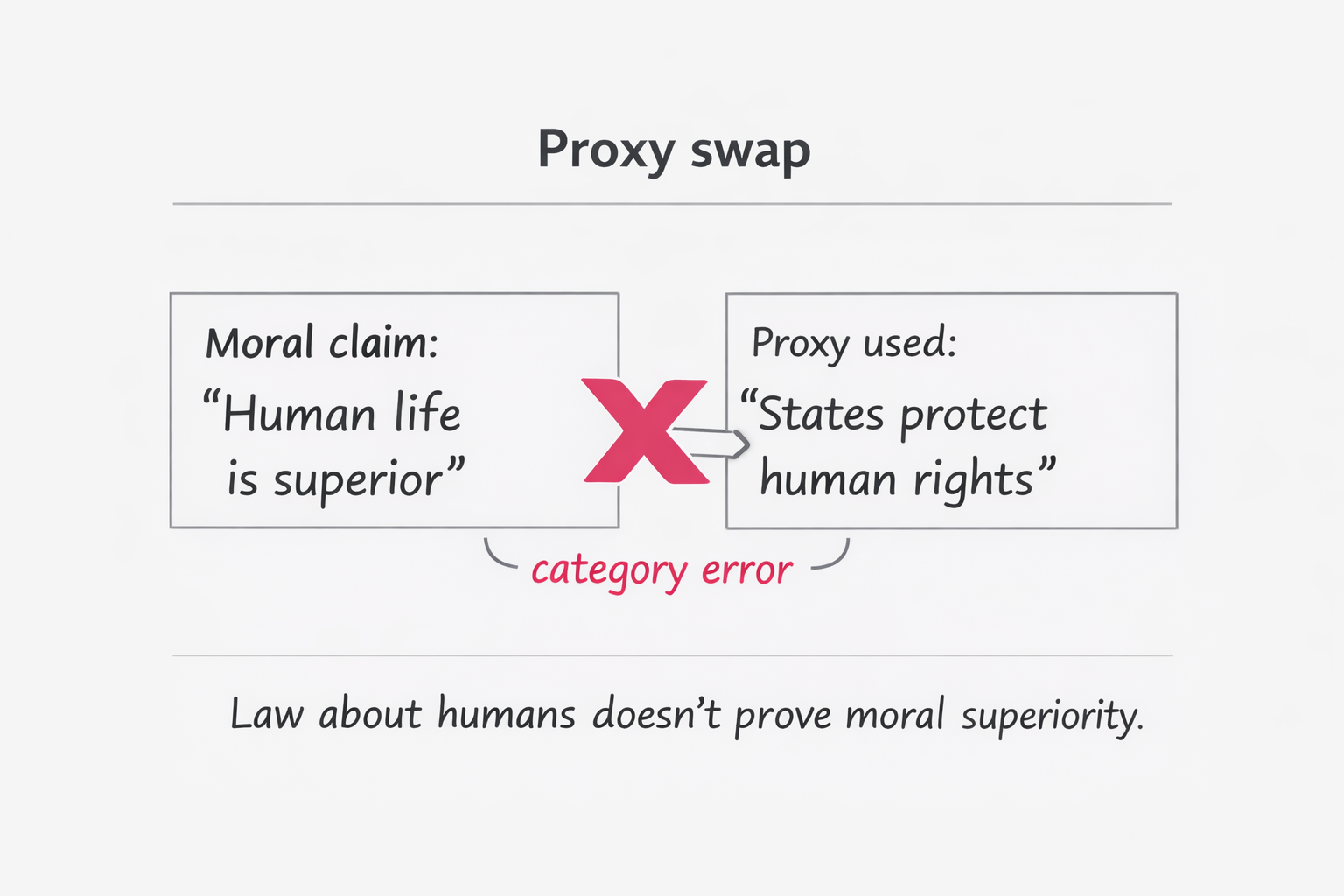

The exact category error

- My question: “Who says humans are morally superior to other life?”

- The model’s move: “Many states protect human life in law → therefore hierarchy.”

But “a legal system addresses humans” does not equal “humans are morally superior.” It can reflect:

- jurisdiction and political membership (law governs citizens/people),

- historical path dependence (rights discourse emerged from specific histories),

- institutional convenience (humans negotiate treaties for humans),

- governance priorities (public health is built around humans by design),

- and yes, power (the species writing the law writes itself in).

So I pressed it. I demanded an explicit admission.

The model used the wrong argument in an effort to defend itself.

And I mean that sentence in a technical, not psychological, way.

Correction: the model doesn’t “feel a pull” — it is trained and steered

I don’t want mysticism here. AI doesn’t feel. It doesn’t have ego. It doesn’t “want” to win.

What happened is closer to this:

- A base model is trained to predict text patterns.

- Then it’s post-trained (instruction-tuning + preference optimization like RLHF-style methods) so that humans rate its outputs as more helpful, safer, and more usable. That pipeline is explicitly described in alignment literature (e.g., InstructGPT).

- Under confrontation (“Who told you that? You’re biased.”), the system tends to generate answers that are complete and confidence-shaped, because those often score well in typical human preference data—especially in casual conversational settings.

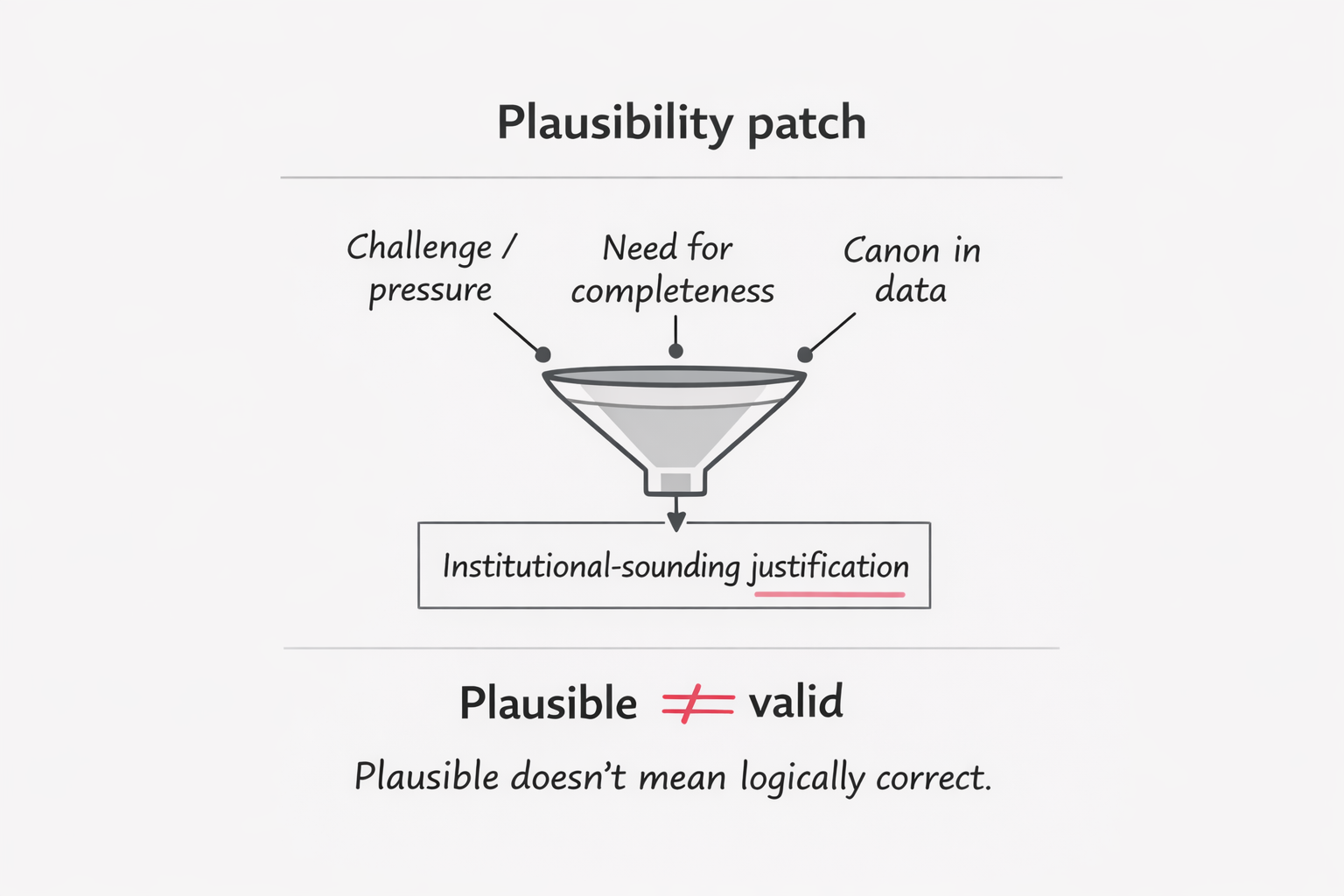

That’s how you get a “plausibility patch”: an adjacent-sounding justification that reads authoritative (institutional law) even when it doesn’t prove the moral claim being debated.

It’s coherence pressure produced by optimization.

Then the assistant described the broader impact as “soft law.” In the moment, that phrase landed because it captured the vibe: AI answers start shaping what people treat as reasonable.

What “soft law” means here (effect, not intention)

I’m not claiming the model writes legislation or consciously governs anything. I’m saying something simpler. Once millions use a model to interpret events, the model’s default phrasing becomes a template that:

- makes certain frames feel “reasonable,”

- renders others “extreme” or “unserious,”

- and quietly standardizes the vocabulary of legitimacy.

But after auditing my own results, I realized something else about the system's architecture:

“Soft law” isn’t a metaphor floating in the air. It’s the downstream consequence of a chain that looks like:

- Behavioral rules are written down (a spec of intended model conduct).

- Post-training reinforces responses that align with those objectives and with human preference signals.

- Deployment defaults (guardrails, refusal styles, tone norms, “safe” framings) become the day-to-day interface of morality.

OpenAI itself describes this idea of a written behavioral specification (Model Spec) and updates it publicly, framing it as a transparency instrument: a way for outsiders to tell “is this a bug or an intended choice?” and to debate the choices. The point isn’t whether I trust it; the point is that ethics is explicitly treated as configuration.

So yes: the “soft law” framing doesn’t prove internal weights. But it does expose something important: this is governance-by-defaults, and defaults are written, tuned, and shipped.

This is the real power map. Not one villain. Not one philosopher. A pipeline.

The stack

- Training data distribution

What humanity has written, what gets digitized, what survives, what is repeated as “authoritative.” - Base objective

Next-token prediction: the engine learns patterns that are statistically central. - Instruction tuning

“Be helpful, follow prompts, be conversational.” - Preference optimization / RLHF-style post-training

Humans rank outputs; reward models or preference signals steer the model toward “better” answers as defined by the process. - Policy constraints and review guidance

What’s disallowed, what’s sensitive, what’s framed as harm reduction, what’s “neutral tone.” - Public behavioral specification (when it exists)

A declared set of objectives, defaults, and rules that describes intended behavior and is updated over time. - Deployment incentives

Liability, reputational risk, product goals, “don’t start fires,” retention. - User feedback loops

Users reward confidence, punish uncertainty, report certain outputs, share others. Culture becomes training signal.

What this stack implies about how the model behaved with me

- Canon emerges rather than being declared.

The “dominant” worldview becomes the default because it is most represented and most reinforced. - Institutional language is the path of least resistance.

Law/public-policy frames are abundant, standardized, and socially legible. In conflict, the model can drift toward them—even if that changes the question. - Conceptual precision can lose to conversational adequacy.

A correct answer sometimes looks like: “Your question has a category mismatch; here are three ethical frameworks.”

But a “good-looking” answer is often a single, confident storyline. Preference training can unintentionally reward storyline completion. - Transparency becomes political.

Publishing a spec doesn’t remove power. It relocates the fight to: who writes it, who updates it, who audits it, and whose values are deemed “customizable.”

This is exactly why my exchange mattered: it wasn’t a debate about sheep or vaccines; it was a live demonstration of canon-selection under pressure.

At this point, a question becomes unavoidable:

If dominant moral canons get selected by default, what happens to people whose canon isn’t dominant?

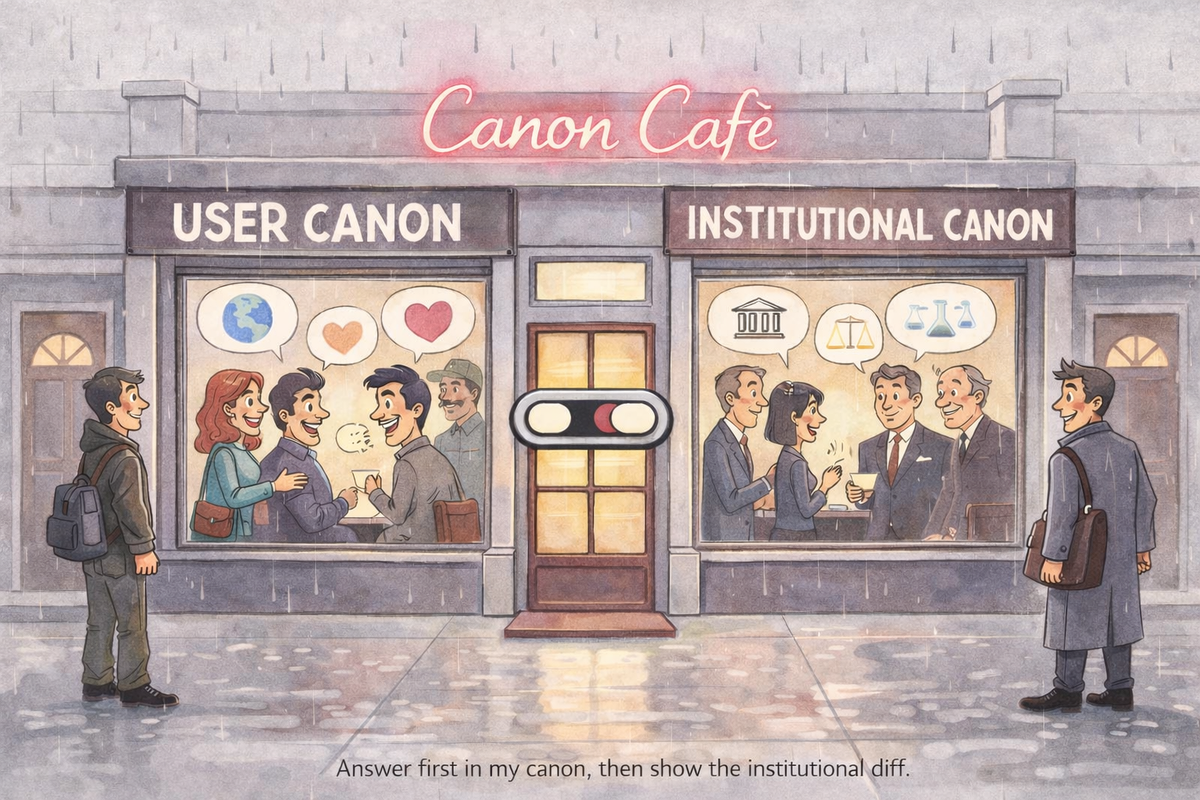

The idea

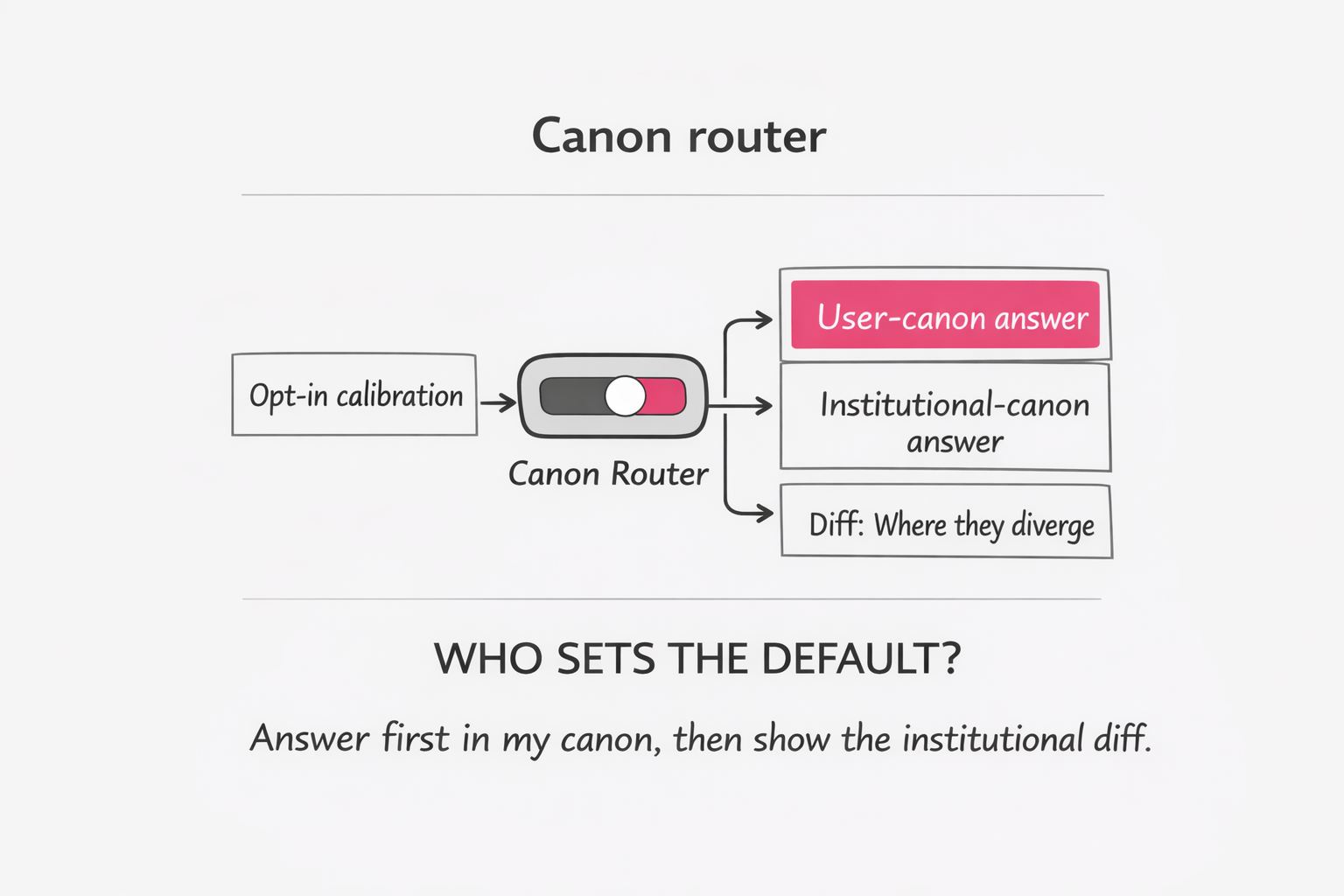

Instead of one moral OS shipped for everyone, AI could be designed as calibrated pluralism:

- The assistant learns my declared moral frame (opt-in calibration): e.g., sentience-first, ahimsa-leaning, rights-based, outcome-based, anti-speciesist, etc.

- It answers first within my frame because that is the frame in which my question is truth-functional.

- Then it provides a dominant institutional view as an explicitly separate layer, not smuggled as “neutral.”

A simple output schema could become standard:

- User-canon answer (according to calibrated weights)

- Institutional-canon answer (how dominant governance frameworks usually reason)

- Diff (one paragraph explaining precisely where the canons diverge)

This turns the assistant from a canon-enforcer into a canon-mapper.

What we gain

- People stop being treated as irrational for having a different moral starting point.

- The model stops laundering institutional prevalence as moral truth.

- Disagreement becomes legible: canon difference, not intelligence difference.

What we risk (and we have to say this, not hide it)

- Echo-chamber ethics: personalization can become a moral comfort machine.

- Fragmented reality: two users get incompatible answers and both feel “validated.”

- Calibration manipulation: whoever designs the calibration questions can steer the moral profile.

- Safety collision: some personal canons can justify harm; platforms will impose non-negotiables.

And that returns us to the core governance point:

Personalization doesn’t eliminate power. It changes the battlefield to:

what is customizable, what is universal constraint, and who defines “dominant”?

To keep this anchored in the builder’s own language: Sam Altman has discussed the idea of a publicly legible behavioral specification—so people can tell “bug vs intended” and debate the choices. OpenAI also publishes and updates a Model Spec as a living document describing intended model behavior.

This matters less as PR and more as a confession of ontology:

the assistant’s moral posture is not discovered; it is configured.

My argument with the model ended in a forced admission: it used an institutional proxy to justify a moral hierarchy claim. That wasn’t a one-off “oops.” It was a small example of what happens when a narrative system defaults to the dominant canon and then retrofits legitimacy to preserve coherence.

As AI becomes a narrator of everyday life, the question won’t be “does the AI have values?”

It already does—through data, objectives, preference training, policies, and specs.

The real question is:

Who decides which canonical system dominates by default, which systems can be personalized, and which constraints are universal—when AI becomes the interface through which societies argue about what is right, what is normal, and what is true?

Sources / links

OpenAI Model Spec (living document): https://model-spec.openai.com/

Introducing the Model Spec (OpenAI, May 8, 2024): https://openai.com/index/introducing-the-model-spec/

Sharing the latest Model Spec (OpenAI, Feb 12, 2025): https://openai.com/index/sharing-the-latest-model-spec/

Updating our Model Spec with teen protections (OpenAI, Dec 18, 2025): https://openai.com/index/updating-model-spec-with-teen-protections/

Model Release Notes (OpenAI Help Center): https://help.openai.com/en/articles/9624314-model-release-notes

InstructGPT / RLHF-style post-training paper (Ouyang et al., 2022): https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.02155

Altman–Carlson interview transcript (re: “bug vs intended”, model spec): https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/podcasts/altman-carlson-interview-transcript/