Aid and Intention: The Strategic Paradox of Humanitarian Relief

Humanitarian aid saves lives — but it can also fuel conflict. This article explores the strategic paradox of relief: how aid becomes both a lifeline and a lever in global power struggles.

Βοήθεια και Πρόθεση: Το Στρατηγικό Παράδοξο της Ανθρωπιστικής Βοήθειας

Πρόλογος

Πρόλογος

Κάποτε, ίσως και περισσότερες από μία φορές, βρέθηκα σε μάθημα μιας σπουδαίας οικονομολόγου ανάπτυξης. Μας έβαλε να τρέχουμε παλινδρόμηση μετά από παλινδρόμηση, κάθε μοντέλο πιο σύνθετο από το προηγούμενο. Στο τέλος του μαθήματος δουλεύαμε κατευθείαν με τα δεδομένα από τη δική της δημοσιευμένη έρευνα — προσεκτικά τυχαιοποιημένα, διορθωμένα για μεροληψία και ελεγμένα από κάθε πιθανή οπτική.

Τα αποτελέσματα ήταν αυστηρά και ανησυχητικά: η ανθρωπιστική βοήθεια, παρότι σχεδιασμένη να ανακουφίζει τον πόνο, μπορεί κάποιες φορές να παρατείνει τη σύγκρουση αντί να τη λύνει. Κι όμως, όσο ακριβείς κι αν ήταν οι παλινδρομήσεις, εγώ έφυγα από την αίθουσα με μια βαθύτερη ανησυχία. Ένιωθα ότι κάτι πιο θεμελιώδες βρισκόταν σε εξέλιξη — ένα στρώμα στρατηγικής, πρόβλεψης και αντιπρόβλεψης, που η στατιστική από μόνη της δεν μπορούσε να αποτυπώσει πλήρως.

Από τα Δεδομένα στη Στρατηγική: Μια Παιγνιοθεωρητική Ματιά

Οι παλινδρομήσεις έδειξαν μια αλήθεια: η βοήθεια μπορεί να αλλάξει τη δυναμική των συγκρούσεων με τρόπους που δεν είναι πάντα διαισθητικοί. Όμως πίσω από αυτούς τους αριθμούς κρύβεται ένα άλλο επίπεδο — η λογική της στρατηγικής αλληλεπίδρασης.

Η θεωρία παιγνίων μας διδάσκει ότι οι δρώντες σπάνια σταματούν στις άμεσες συνέπειες. Σκέφτονται τι θα κάνουν οι άλλοι, τι νομίζουν οι άλλοι ότι θα κάνουν, και πώς αυτές οι πεποιθήσεις διαχέονται. Οι οικονομολόγοι συχνά μιλούν για σκέψη δεύτερης και υψηλότερης τάξης.

Ένα γνώριμο παράδειγμα είναι το σκάκι: κάθε κίνηση κρίνεται όχι μόνο από το τι πετυχαίνει άμεσα αλλά και από τις αντεπιθέσεις που θα προκαλέσει δύο, τρία ή περισσότερα βήματα αργότερα.

- Πρώτου επιπέδου: «Η βοήθεια κρατά τους ανθρώπους ζωντανούς.»

- Δεύτερου επιπέδου: «Ο αντίπαλός μου μπορεί να εκμεταλλευτεί αυτή τη βοήθεια.»

- Τρίτου επιπέδου: «Αν την εκμεταλλευτούν, μπορώ να το χρησιμοποιήσω ως δικαιολογία για σκληρότερα μέτρα.»

- Νιοστού επιπέδου: «Ξέρουν ότι ξέρω πως μπορεί να την εκμεταλλευτούν…»

Αυτό που αρχικά έμοιαζε σαν μια στατιστική κανονικότητα — ότι η βοήθεια παρατείνει τις συγκρούσεις — αποκαλύφθηκε ως κάτι πιο σύνθετο: ένα επαναλαμβανόμενο παιχνίδι κινήσεων και αντεπιθέσεων, όπου οι ανθρωπιστικές ροές γίνονται μέρος μιας μακροπρόθεσμης στρατηγικής.

1. Η Ανθρωπιστική Βοήθεια ως Δίκοπο Μαχαίρι

«Αυξήσεις στην αμερικανική επισιτιστική βοήθεια αυξάνουν την εμφάνιση και τη διάρκεια εμφυλίων συγκρούσεων.» — Nunn & Qian, American Economic Review (2014)

«Η βία ανταρτών αυξήθηκε σε περιοχές που ήταν επιλέξιμες για βοήθεια στο πλαίσιο μεγάλου προγράμματος.» — Crost, Felter & Johnston, AER (2016)

«Τα σοκ στη βοήθεια αυξάνουν την πιθανότητα εμφυλίων συγκρούσεων μέσω μεταβολών στη διαπραγματευτική ισχύ.» — Nielsen et al., AJPS (2011)

«Η ανθρωπιστική βοήθεια … συνδέεται με υψηλότερα επίπεδα βίας ανταρτών.» — Reed Wood, AidData WP (2018)

«Υπό ορισμένες συνθήκες, η παροχή υπηρεσιών μειώνει τη βία ανταρτών.» — Berman, Shapiro & Felter, Journal of Political Economy (2011)

Οι μηχανισμοί που έχουν εντοπιστεί περιλαμβάνουν:

- Εκτροπή και φορολόγηση: ένοπλες ομάδες μπορεί να κατασχέσουν μέρος της βοήθειας.

- Νομιμοποίηση: ο έλεγχος της βοήθειας ενισχύει την πολιτική εξουσία.

- Σαμποτάζ: τα έργα μπορεί να γίνουν στόχος επιθέσεων.

- Αστάθεια: ξαφνικές αυξήσεις ή μειώσεις αλλάζουν τις ισορροπίες ισχύος.

- Παροχή υπηρεσιών: σε ισχυρά θεσμικά περιβάλλοντα, η βοήθεια μπορεί να μειώσει τη βία.

Ιστορική σημείωση: Η Σομαλία στις αρχές της δεκαετίας του 1990 έγινε μια τραγική μελέτη περίπτωσης. Οι οργανισμοί αρωγής κατέγραψαν πώς οι πολιτοφυλακές κατέλαβαν επισιτιστική βοήθεια, φορολόγησαν κομβόι και μπλόκαραν παραδόσεις. Η Human Rights Watch ανέφερε ότι «η λεηλασία των σοδειών και η κλοπή του ζωικού κεφαλαίου … διασφάλισαν ότι αυτές οι κοινότητες θα λιμοκτονούσαν ή θα εξαρτιόνταν από τη διεθνώς δωρηθείσα τροφή» (HRW, 1993). Η βοήθεια που προοριζόταν για τα θύματα λιμού ταυτόχρονα ενίσχυε τον έλεγχο των ένοπλων ομάδων.

2. Το Στρατηγικό Παράδοξο

Φανταστείτε έναν κυρίαρχο δρώντα που γνωρίζει καλά αυτή τη βιβλιογραφία. Αντιμετωπίζει έναν περιθωριοποιημένο αντίπαλο: ριζοσπαστικό, εξαρτημένο από ανθρωπιστικές ροές, ανίκανο να επιβιώσει χωρίς εξωτερική βοήθεια.

Αντί να μπλοκάρει τη βοήθεια, ο κυρίαρχος δρών επιτρέπει ή ανέχεται τη ροή της. Αυτή η παράδοξη επιλογή δημιουργεί μια εύθραυστη ισορροπία:

- Επιβίωση αλλά αδυναμία — ο αντίπαλος ζει, αλλά παραμένει εξαρτημένος.

- Νομιμοποίηση μέσω σπάνιων πόρων — κυβερνά μέσω δελτίου, όχι μέσω ανάπτυξης.

- Προβλέψιμη επιθετικότητα — η βοήθεια μπορεί να τροφοδοτεί χαμηλής έντασης συγκρούσεις, αλλά αυτές παραμένουν διαχειρίσιμες.

- Στρατηγική παγίδευση — αν ο αντίπαλος κλιμακώσει απότομα, ο κυρίαρχος δρών μπορεί να πει: «Επιτρέψαμε να συνεχιστεί η βοήθεια, κι εκείνοι τη μετέτρεψαν σε βία. Τώρα δικαιολογούνται σκληρότερα μέτρα.»

Σε ένα τέτοιο σενάριο, η ανθρωπιστική βοήθεια δεν είναι απλώς ανακούφιση — γίνεται στρατηγικό μοχλός σε ένα επαναλαμβανόμενο παιχνίδι.

3. Η Ανθρωπιστική Βοήθεια ως Πολιτική Οικονομία

Αυτό το παράδοξο αντανακλά γνωστές οικονομικές λογικές:

- Ηθικός κίνδυνος: όπως η ασφάλιση, η βοήθεια μπορεί να ενθαρρύνει πιο ριψοκίνδυνες συμπεριφορές.

- Πρόβλημα δέσμευσης: οι μεταβολές στη βοήθεια αλλάζουν τη διαπραγματευτική ισχύ αλλά όχι τα παράπονα.

- Στρατηγική υπομονή: ένας κυρίαρχος δρών μπορεί να προτιμά να κρατά έναν εχθρό ζωντανό — αδύναμο, ριζοσπαστικό, εξαρτημένο — μέχρι να ωριμάσουν οι συνθήκες για αποφασιστική δράση.

Όπως έγραψαν οι Nunn & Qian: «Η επισιτιστική βοήθεια μπορεί ακούσια να παρατείνει τις συγκρούσεις επιτρέποντας στους αντιμαχόμενους να διατηρήσουν τη μαχητική τους ικανότητα.»

Και όπως προειδοποίησαν οι Crost, Felter & Johnston: «Η αναπτυξιακή βοήθεια μπορεί να προκαλέσει βία αν οι αντάρτες αντιληφθούν τα έργα ως απειλή στον έλεγχό τους.»

4. Ένα Υποθετικό Σενάριο

Φανταστείτε μια περιοχή διχασμένη από εμφύλια σύγκρουση. Οι πολίτες επιβιώνουν χάρη σε κομβόι βοήθειας και οικονομικές ενέσεις. Μια περιθωριοποιημένη φατρία κυβερνά μόνο επειδή αυτές οι ροές τη συντηρούν. Ο κυρίαρχος δρών θα μπορούσε να τις σταματήσει — αλλά επιλέγει να μην το κάνει.

Για χρόνια, η φατρία παραμένει ριζοσπαστική αλλά στάσιμη: φοβισμένη αλλά όχι νομιμοποιημένη, ζωντανή αλλά όχι ακμάζουσα. Η σποραδική βία συνεχίζεται. Κάποια μέρα όμως έρχεται η κλιμάκωση.

Ο κυρίαρχος δρών μπορεί να απαντήσει: «Ανεχθήκαμε την ύπαρξή τους, επιτρέψαμε τη ροή βοήθειας, κι εκείνοι τη μετέτρεψαν σε βία. Τώρα δικαιολογούνται σκληρότερα μέτρα.»

Σε αυτό το υποθετικό σενάριο, η βοήθεια εξελίσσεται από σωσίβιο σε μέρος μιας στρατηγικής αιτιολόγησης για κλιμάκωση.

Κι όμως, η στρατηγική σπάνια είναι απεριόριστη. Η πίεση και ο έλεγχος μπορούν να λειτουργήσουν — μέχρι να πάψουν. Όπως στα χρηματοοικονομικά, όπου η σταθερότητα ανατρέπεται ξαφνικά σε κατάρρευση, έτσι και στη σύγκρουση υπάρχει σημείο καμπής.

5️⃣ Το Παράδοξο Υπερβολής της Βοήθειας (Aid Overshoot Paradox)

Στα χρηματοοικονομικά, οι οικονομολόγοι μιλούν για τη «στιγμή Minsky» — το σημείο καμπής όπου η μόχλευση, που προηγουμένως στήριζε την ανάπτυξη, ξαφνικά γυρίζει σε κατάρρευση. Κάτι παρόμοιο μπορεί να συμβεί στη δυναμική των συγκρούσεων όταν τέμνονται η βοήθεια και η στρατηγική.

Ένας κυρίαρχος δρών μπορεί να ανεχθεί ή να περιορίσει τις ανθρωπιστικές ροές για να κρατά έναν αντίπαλο αδύναμο, κατακερματισμένο και εξαρτημένο. Εντός ορίων, αυτή η προσέγγιση μπορεί να πετύχει: ο αντίπαλος επιβιώνει αλλά παραμένει περιθωριακός, χωρίς τους πόρους για να οικοδομήσει νομιμοποίηση.

Ωστόσο η στρατηγική οριοθετείται από την αντίληψη. Αν η πίεση υπερβεί το μέτρο — αν η σκληρότητα γίνει υπερβολικά ορατή ή δυσανάλογη — η λογική μπορεί να αντιστραφεί. Αυτό που κάποτε συντηρούσε τον έλεγχο μπορεί να πυροδοτήσει ένα σημείο καμπής όπου η συμπάθεια αναδιατάσσεται και ο αντίπαλος, παραδόξως, κερδίζει αναγνώριση.

Για τους ριζοσπάστες, η ίδια η επιβίωση μπορεί να είναι στρατηγική. Η αντοχή σε ακραίο κόστος σηματοδοτεί ανθεκτικότητα· δοκιμάζει αν το διεθνές σύστημα θα τους αναγνωρίσει τελικά. Έτσι, η αναγνώριση γίνεται η καθυστερημένη απόδοση της επιμονής υπό πυρά.

Το παράδοξο είναι σαφές: οι ίδιες κινήσεις που σχεδιάστηκαν για να διασφαλίσουν μόνιμη αδυναμία μπορεί, όταν ωθούνται πέρα από το όριο, να παράξουν νομιμοποίηση. Όπως στα χρηματοοικονομικά, όπου η σταθερότητα εκτρέπεται σε κατάρρευση, έτσι και στη σύγκρουση η ανθρωπιστική πίεση μπορεί να τρέφει τον έλεγχο έως ότου παράξει το αντίθετό της — την αθέλητη ανύψωση εκείνων που στόχευε να εξαφανίσει.

Αυτό το ονομάζω Παράδοξο Υπερβολής της Βοήθειας (Aid Overshoot Paradox). Οι ροές βοήθειας, όταν γίνονται ανεκτές ή χειραγωγούνται από έναν κυρίαρχο δρώντα, μπορούν αρχικά να λειτουργήσουν ως εργαλείο ελέγχου. Οι πολίτες επιβιώνουν, η ασθενέστερη παράταξη παραμένει εξαρτημένη και η σταθερότητα — έστω εύθραυστη — διατηρείται. Η ίδια η παρουσία της βοήθειας καταπνίγει τη δυνατότητα των περιθωριοποιημένων δρώντων να αξιώσουν νομιμοποίηση: αντέχουν, αλλά δεν ακμάζουν.

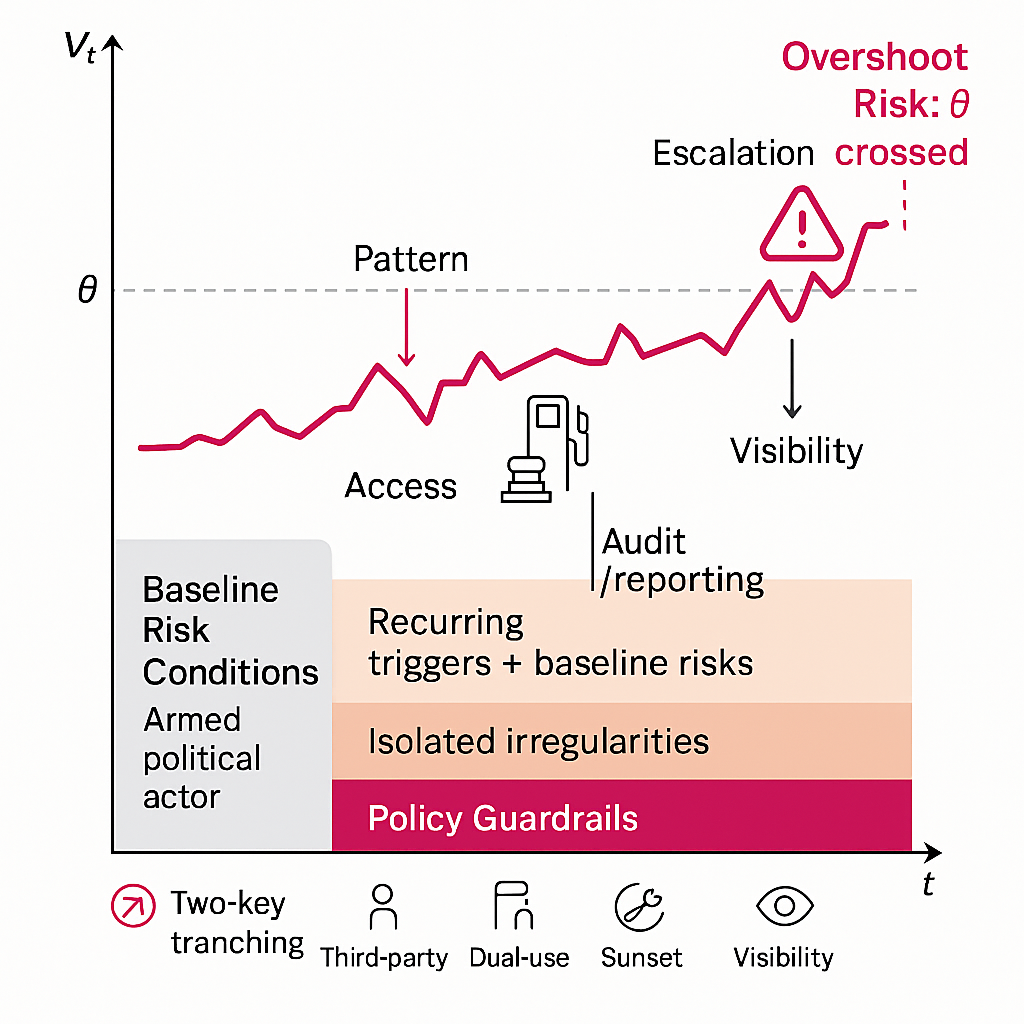

📊 Παράδοξο Υπερβολής της Βοήθειας: Δυναμικές Κατωφλίου (Αντιλαμβανόμενη Σκληρότητα vs Μεταβολή Νομιμοποίησης)

Καμπύλη S που δείχνει τη μεταβολή νομιμοποίησης (ΔL) ως προς την αντιλαμβανόμενη σκληρότητα (Ct). Κάτω από το κατώφλι θ, η βοήθεια σταθεροποιεί μέσω εξάρτησης· πάνω από το θ, ο μηχανισμός αντιστρέφεται και η νομιμοποίηση αυξάνεται.

Τυποποίηση. Ορίζουμε τις βασικές μεταβλητές:

- At = ανθρωπιστική βοήθεια στη χρονική στιγμή t

- Pt = πίεση/έλεγχος που ασκεί ο κυρίαρχος δρών

- Vt = ορατότητα αυτής της πίεσης σε εξωτερικά ακροατήρια

- Ct = αντιλαμβανόμενη σκληρότητα στη στιγμή t (συνάρτηση των Pt και Vt)

- Dt = εξάρτηση της ασθενέστερης παράταξης

- Lt = νομιμοποίηση της ασθενέστερης παράταξης

- θ = κατώφλι αντίληψης πέρα από το οποίο η σκληρότητα γίνεται αντιπαραγωγική

- L* = επίπεδο νομιμοποίησης στο οποίο επέρχεται εξωτερική αναγνώριση

C_t = P_t × V_t (αντιλαμβανόμενη σκληρότητα, κλιμακωμένη από την ορατότητα)

D_{t+1} = φ D_t + a A_t − ℓ L_t (η βοήθεια αυξάνει την εξάρτηση· η νομιμοποίηση τη μειώνει)

ΔL_{t+1} =

-λ A_t + ε, if C_t < θ (σταθεροποίηση: καταστολή νομιμοποίησης)

γ (C_t − θ) + η A_t, if C_t ≥ θ (υπέρβαση κατωφλίου: άνοδος νομιμοποίησης)

Recognition event:

R_t = 1{ L_t ≥ L* } (εξωτερική αναγνώριση μόλις η νομιμοποίηση υπερβεί το κατώφλι)

Ερμηνεία γραφήματος: Το παράδοξο δείχνει πως η βοήθεια συντηρεί την εξάρτηση έως ότου η αντιλαμβανόμενη σκληρότητα (Ct) διαβεί το κατώφλι (θ). Κάτω από το θ, η νομιμοποίηση καταστέλλεται και ο έλεγχος διατηρείται· πάνω από το θ, η υπερβολική ορατότητα της σκληρότητας αναδιατάσσει τη συμπάθεια και η νομιμοποίηση αυξάνεται αντί να περιορίζεται.

- Άξονας x: Αντιλαμβανόμενη Σκληρότητα (Ct) — πόσο έντονα τα εξωτερικά ακροατήρια καταγράφουν την πίεση του κυρίαρχου δρώντα.

- Άξονας y: Μεταβολή Νομιμοποίησης (ΔL) — αν η νομιμοποίηση της ασθενέστερης παράταξης μειώνεται (αρνητική) ή αυξάνεται (θετική).

6️⃣ Το Ανθρωπιστικό Δίλημμα

Η βοήθεια σε εμπόλεμες ζώνες δεν είναι ποτέ απλώς βοήθεια.

- Για τους πολίτες, είναι επιβίωση.

- Για τις περιθωριοποιημένες ομάδες, μπορεί να είναι καύσιμο.

- Για τους κυρίαρχους δρώντες, μπορεί να γίνει μοχλός — διατηρώντας έναν αντίπαλο ζωντανό ακριβώς τόσο ώστε να παρουσιαστεί ως ανεπίδεκτος διόρθωσης.

Κι όμως, ακόμη και οι μοχλοί έχουν όρια. Αν πιεστούν υπερβολικά, αυτό που κάποτε ενίσχυε τον έλεγχο μπορεί να αναστραφεί σε αναγνώριση. Το σημείο καμπής, όπως μια χρηματοοικονομική κατάρρευση, δεν έρχεται σταδιακά αλλά απότομα — τη στιγμή που η στρατηγική υπερβαίνει τα όριά της.

Ιδού το δίλημμα: η ανακούφιση δεν μπορεί να ξεφύγει από τη λογική της στρατηγικής, και η στρατηγική δεν μπορεί να ξεφύγει από τον κίνδυνο της υπέρβασης. Η ανθρωπιστική βοήθεια στέκεται ανάμεσα στα δύο, ταυτόχρονα σωσίβιο και δυνητική ευθύνη.

Στο τέλος της ημέρας, όλοι μας ασκούμε στρατηγική σκέψη — προβλέπουμε τις ενέργειες των άλλων, ετοιμάζουμε εναλλακτικές, ζυγίζουμε βραχυπρόθεσμα ανταλλάγματα έναντι μακροπρόθεσμων αποτελεσμάτων. Δεν πρέπει να μας ξαφνιάζει ότι το ίδιο κάνουν οι ηγέτες μπροστά σε πολέμους και ανθρωπιστικές κρίσεις. Αλλά ας μας θυμίζει κάτι ακόμη: ακόμη και η καλύτερη στρατηγική, αν πιεστεί πέρα από το όριό της, μπορεί να στραφεί εναντίον του δημιουργού της.

7️⃣ Παρακολούθηση υπο-κατώφλιας εργαλειοποίησης της βοήθειας

Το ερώτημα που σπάνια θέτουμε είναι απλό αλλά ανησυχητικό: όταν παρέχουμε ανθρωπιστική βοήθεια, βοηθάμε πραγματικά — ή μερικές φορές κάνουμε τα πράγματα χειρότερα;

Το παράδοξο υποδεικνύει έναν διαφορετικό τρόπο οργάνωσης της εποπτείας. Αντί να ρωτάμε μόνο «φτάνει η βοήθεια στους ανθρώπους που τη χρειάζονται;», πρέπει επίσης να ρωτάμε «παραμένουν κρυφά τα μοτίβα παρεμπόδισής της;»

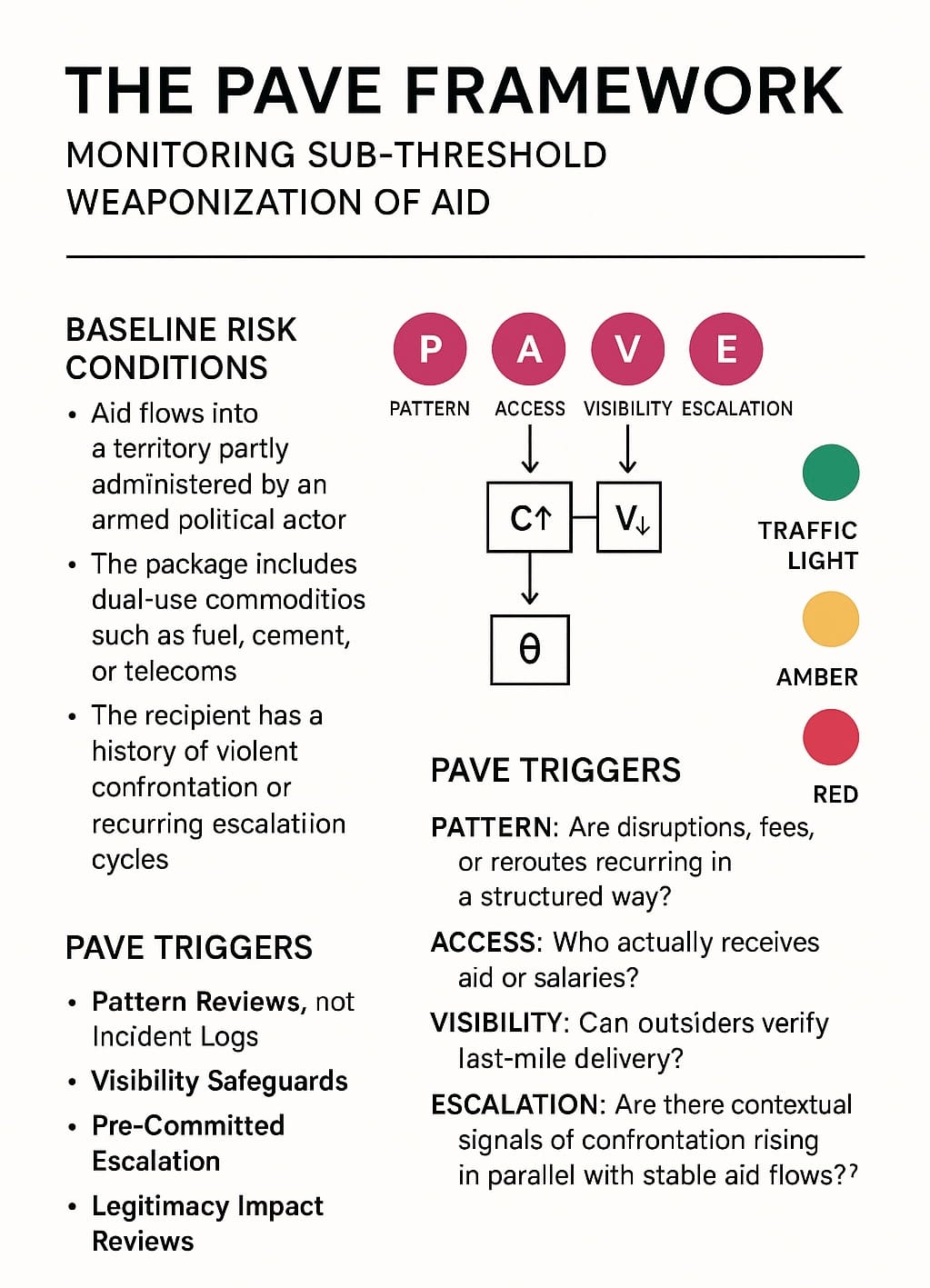

Το Πλαίσιο PAVE: Pattern – Access – Visibility – Escalation

Βασικές Συνθήκες Κινδύνου (πάντα υπό παρακολούθηση)

- Η βοήθεια ρέει σε περιοχή που διοικείται εν μέρει από ένοπλο πολιτικό φορέα.

- Το πακέτο περιλαμβάνει αγαθά διπλής χρήσης όπως καύσιμα, τσιμέντο ή τηλεπικοινωνίες.

- Ο αποδέκτης έχει ιστορικό βίαιης αντιπαράθεσης ή επαναλαμβανόμενων κύκλων κλιμάκωσης.

Όταν υπάρχουν αυτές οι συνθήκες, ακόμη και μικρές ανωμαλίες πρέπει να αντιμετωπίζονται με προσοχή.

Δείκτες PAVE

- Pattern (Μοτίβο): Επαναλαμβάνονται οι καθυστερήσεις, τα «διόδια» ή οι αναδρομολογήσεις με δομημένο τρόπο; Η επανάληψη δείχνει σκόπιμη διαμόρφωση και όχι τυχαία περιστατικά.

- Access (Πρόσβαση): Ποιος λαμβάνει πραγματικά τη βοήθεια ή τους μισθούς; Αν οι λίστες ή οι προμηθευτές είναι «κλειστά κυκλώματα», η βοήθεια μπορεί να παγιώσει εξάρτηση.

- Visibility (Ορατότητα): Μπορούν εξωτερικοί φορείς να επαληθεύσουν την τελική διανομή; Αν η αναφορά είναι αδιαφανής ή εξαρτάται από τα συστήματα του ίδιου του φορέα, αυξάνεται ο κίνδυνος υπο-κατώφλιας χειραγώγησης.

- Escalation (Κλιμάκωση): Εμφανίζονται ενδείξεις αντιπαράθεσης (ρητορική, εκπαίδευση, οχύρωση) παράλληλα με σταθερές ροές βοήθειας; Αν ναι, το παράδοξο κινείται προς υπερβολή.

Κυκλοφοριακό Φανάρι

- Πράσινο: Μεμονωμένες ανωμαλίες με σαφείς εξηγήσεις.

- Κίτρινο: Ένας ή περισσότεροι δείκτες PAVE επαναλαμβάνονται σε συνδυασμό με βασικούς κινδύνους.

- Κόκκινο: Επιλεκτική πρόσβαση + αδιαφάνεια + ενδείξεις κλιμάκωσης υπό βασικές συνθήκες → προειδοποίηση ότι η βοήθεια μπορεί να περάσει το όριο υπερβολής (θ).

🔽 Κάντε κλικ για να αναπτύξετε: Πρακτική Εφαρμογή

P — Pattern (Μοτίβο): Ελέγξτε αν οι μεταβιβάσεις γίνονται σε σταθερό ρυθμό, αν οι εξαιρέσεις κανονισμών επαναλαμβάνονται ή αν διαφορετικές ροές συγχρονίζονται. Σήμα κινδύνου: η «προσωρινή» εξαίρεση που επαναλαμβάνεται για τρίτη φορά.

A — Access (Πρόσβαση): Ελέγξτε αν οι ροές σταθεροποιούν μισθοδοσίες ή προμήθειες μέσω φορέων που ελέγχονται από τον ίδιο δρώντα. Σήμα κινδύνου: δύο ή περισσότεροι κύριοι δίαυλοι ελέγχονται από το ίδιο δίκτυο χωρίς ανεξάρτητη αμφισβήτηση.

V — Visibility (Ορατότητα): Ελέγξτε αν οι τελικές διανομές μπορούν να επαληθευτούν ανεξάρτητα, αν υπάρχουν μετρήσεις καυσίμων/ενέργειας, ή αν η δημοσιοποίηση καθυστερεί. Σήμα κινδύνου: αύξηση ροών + αύξηση καθυστερήσεων στην αναφορά.

E — Escalation (Κλιμάκωση): Ελέγξτε αν υπάρχουν ενδείξεις στρατιωτικής προετοιμασίας ή ρητορικής αντιπαράθεσης που ενισχύονται παράλληλα με τη ροή βοήθειας. Σήμα κινδύνου: δύο ή περισσότερα τέτοια σήματα μαζί με ανεπίλυτα προβλήματα στα υπόλοιπα PAVE.

Συνολικό αποτέλεσμα: Έκδοση πρώιμης προειδοποίησης με τη διατύπωση: «Τρέχουσα διαμόρφωση δημιουργεί κίνδυνο υπερβολής: επαναλαμβανόμενη ρευστότητα + ελεγχόμενη πρόσβαση + χαμηλή ορατότητα + αυξανόμενα σήματα ικανότητας».

8️⃣ Κανόνες Σχεδιασμού Πολιτικής

- Ανασκοπήσεις Μοτίβων, όχι Μητρώα Περιστατικών: Η εποπτεία πρέπει να εξετάζει αν οι ανωμαλίες επαναλαμβάνονται, όχι μόνο να καταγράφει μεμονωμένα γεγονότα.

- Εγγυήσεις Ορατότητας: Οι δωρητές πρέπει να επενδύουν σε μηχανισμούς που μειώνουν τις καθυστερήσεις στην αναφορά και περιορίζουν την εξάρτηση από δεδομένα που ελέγχει ο δρών.

- Προ-δεσμευμένη Κλιμάκωση: Πρέπει να οριστεί εκ των προτέρων πώς η μετάβαση από Κίτρινο σε Κόκκινο οδηγεί σε ανεξάρτητη παρακολούθηση ή διεθνή επανεξέταση.

- Αξιολογήσεις Νομιμοποίησης: Μεγάλα πακέτα βοήθειας πρέπει να εκτιμώνται όχι μόνο για τα ανθρωπιστικά τους αποτελέσματα αλλά και για το πώς μπορεί να αλλάξουν τις αντιλήψεις νομιμοποίησης αν χειραγωγηθούν.

Γιατί Έχει Σημασία

Οι υπάρχουσες προσεγγίσεις είτε δίνουν έμφαση στην ηθική των προγραμμάτων (Do No Harm) είτε εστιάζουν σε ανοιχτές πρακτικές λιμοκτονίας και πολιορκίας. Το PAVE στοχεύει στη γκρίζα ζώνη ενδιάμεσα: στις λεπτές χειραγωγήσεις που γίνονται ανεκτές επειδή παραμένουν κρυφές. Οργανώνοντας την εποπτεία γύρω από Μοτίβο, Πρόσβαση, Ορατότητα και Κλιμάκωση, μπορούμε τουλάχιστον εννοιολογικά να εντοπίσουμε πότε οι ροές βοήθειας τείνουν προς υπερβολή — και να δράσουμε διορθωτικά πριν αντιστραφεί η νομιμοποίηση.

Συμπληρωματικά Μέτρα Πολιτικής

- Διπλή-κλείδα στις δόσεις: κάθε δόση παγώνει αυτόματα αν δεν φτάσουν έγκαιρα ανεξάρτητες επαληθεύσεις και μετρήσεις αγαθών.

- Περίφραξη μέσω μη-μετρητών: όπου είναι δυνατό, αντικατάσταση με κουπόνια ή e-cards σε προεγκεκριμένους προμηθευτές.

- Ανεξάρτητη επιβεβαίωση μισθοδοσίας: απαιτείται δειγματοληπτικός έλεγχος και μηχανισμός αμφισβήτησης.

- Σημεία ελέγχου διπλής χρήσης: μετρήσεις επί τόπου + γεω-εντοπισμός· αν λείπουν, η δόση αναβάλλεται.

- Μηχανισμοί λήξης & ασφάλειας: οι ροές λήγουν αυτόματα αν δεν ανανεωθούν μετά από PAVE review· κάθε κόκκινο σήμα οδηγεί σε περίοδο «παγώματος».

- Κίνητρα ορατότητας: μικρή χρηματοδοτική προσαύξηση μόνο όταν βελτιώνεται η ποιότητα αναφοράς.

Αυτές οι κινήσεις αυξάνουν το κόστος υπέρβασης του θ για οποιονδήποτε επιχειρήσει να εργαλειοποιήσει τη βοήθεια και προσφέρουν ένα αμυντικό επιχείρημα όταν τίθεται το ερώτημα: «Γιατί επιβραδύνατε ή ανασχεδιάσατε τη χρηματοδότηση;»

As Adam Smith described the invisible hand, economists have been using models to define and explain the forces that shape our world. This model distills conflict’s complexity into a sequence where aid tolerated becomes dependence, dependence invites escalation, and escalation flips into legitimacy once the hand of such forces can no longer be unseen.

Prologue

I once, perhaps more than once, sat in a class taught by a great development economist. She had us run regression after regression, each model more complex than the last. By the end of the course, we were working directly with the data from her own published research — carefully randomized, bias-adjusted, and tested from every angle.

The results were rigorous and unsettling: humanitarian aid, designed to relieve suffering, can sometimes prolong conflict instead of resolving it. Yet as precise as the regressions were, I left the classroom with a broader unease. It felt as though there was something deeper at work — a layer of strategy, of anticipation and counter-anticipation, that statistics alone could not fully capture.

From Data to Strategy: A Game-Theoretic View

The regressions showed one truth: aid can change conflict dynamics in ways that are not always intuitive. But behind those numbers lies another layer — the logic of strategic interaction.

Game theory teaches us that actors rarely stop at immediate consequences. They think about what others will do, what others think they will do, and how those beliefs cascade. Economists sometimes call this second-order and higher-order thinking.

A familiar example is chess: every move is judged not only by what it accomplishes immediately but also by the counter-moves it will invite two, three, or more steps ahead.

- First-order: “Aid keeps people alive.”

- Second-order: “My opponent may exploit that aid.”

- Third-order: “If they exploit it, I can use that as justification for harsher action.”

- Nth-order: “They know that I know they may exploit it…”

What at first seemed like a statistical regularity — aid prolongs conflict — revealed itself as something more complex: a repeated game of moves and countermoves, where humanitarian flows become part of long-term strategy.

“Increases in U.S. food aid increase incidence and duration of civil conflict.” — Nunn & Qian, American Economic Review (2014)

“Insurgent violence increased in areas eligible for aid under a large program.” — Crost, Felter & Johnston, AER (2016)

“Aid shocks increase likelihood of civil conflict via bargaining shifts.” — Nielsen et al., AJPS (2011)

“Humanitarian aid … associated with higher levels of rebel violence.” — Reed Wood, AidData WP (2018)

“Under certain conditions, service provision reduces insurgent violence.” — Berman, Shapiro & Felter, Journal of Political Economy (2011)

The mechanisms identified include:

- Diversion and taxation: armed groups may capture part of the aid.

- Legitimacy: controlling relief strengthens political authority.

- Sabotage: projects may invite attacks.

- Volatility: sudden surges or cuts shift power balances.

- Service provision: in strong governance contexts, aid can indeed reduce violence.

Historical note: Somalia in the early 1990s became a tragic case study. Relief agencies documented how militias seized food aid, taxed convoys, and blocked deliveries. Human Rights Watch reported that “the looting of harvests and the theft of livestock … ensured that these communities would starve or remain at the mercy of internationally donated food” (HRW, 1993). Aid intended for famine victims was simultaneously reinforcing the control of armed groups.

Imagine a dominant actor familiar with this literature. They face a marginalized opponent: radical, dependent on humanitarian flows, unable to survive without external assistance.

Rather than always blocking aid, a dominant actor may allow or tolerate it. Historical cases suggest that this tolerance can create a fragile equilibrium:

- Survival but weakness — the opponent lives on, but remains dependent.

- Legitimacy through scarcity — they govern through rationing, not development.

- Predictable aggression — aid can fuel low-level flare-ups, but these remain manageable.

- Strategic entrapment — if the opponent escalates sharply, the dominant actor can argue: “We allowed aid to continue, and they turned it into violence. Stronger measures are now justified.”

In such a scenario, humanitarian aid is not just relief — it becomes a strategic lever in a repeated game.

This logic has echoes in Sri Lanka, where the LTTE taxed relief while Colombo tolerated flows into rebel zones; in Chechnya, where Moscow allowed convoys that insurgents siphoned.

This paradox reflects familiar economic logics:

- Moral hazard: like insurance, aid can encourage riskier behavior.

- Commitment problem: shifts in aid change bargaining power but not grievances.

- Strategic patience: a dominant actor may prefer to keep an enemy alive — weak, radical, dependent — until conditions align for decisive action.

As Nunn & Qian put it:

“Food aid may unintentionally prolong conflict by enabling belligerents to maintain fighting capacity.”

And as Crost, Felter & Johnston warn:

“Development assistance can provoke violence if insurgents perceive projects as threats to their control.”

Picture a region fractured by civil conflict. Civilians survive on aid convoys and cash infusions. A marginalized faction rules only because these flows sustain them. The dominant actor could shut them off — but chooses not to.

For years, the faction remains radical yet stagnant: feared but not legitimate, alive but not thriving. Sporadic violence persists. Then one day, escalation arrives.

The dominant actor might respond: “We tolerated their existence, we allowed aid to flow, and they turned it into violence. Now stronger measures are warranted.”

In this hypothetical, aid evolves from a lifeline to part of a strategic justification for escalation.

Yet strategy is rarely boundless. Pressure and control can work—until they don’t. Just as in finance, where stability flips suddenly into collapse, conflict has its own tipping point.

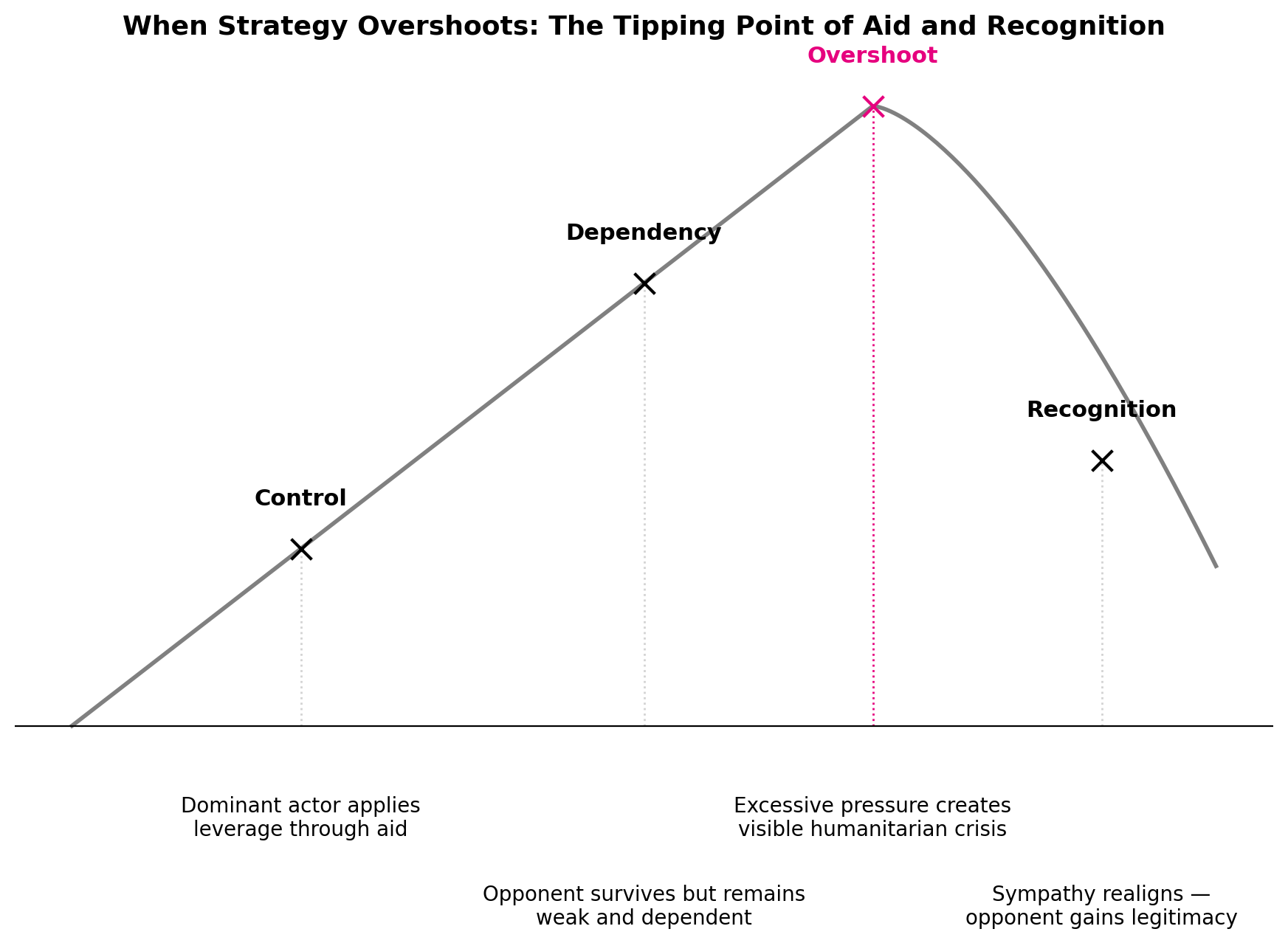

In finance, economists speak of a Minsky moment — the tipping point where leverage, which once sustained growth, suddenly flips into collapse. Something similar can occur in conflict dynamics when aid and strategy intersect.

A dominant actor may tolerate or restrict humanitarian flows to keep an opponent weak, fragmented, and dependent. Within limits, this approach can succeed: the adversary survives but remains marginal, lacking the resources to build legitimacy.

Yet strategy is bounded by perception. If pressure overshoots — if cruelty becomes too visible or disproportionate — the logic can reverse. What once sustained control can trigger a tipping point in which sympathy realigns and the opponent paradoxically gains recognition.

For radicals, survival itself can be a strategy. Enduring extreme costs signals resilience; it tests whether the international system will eventually acknowledge them. In this way, recognition becomes the delayed payoff for persistence under fire.

The paradox is stark: the same moves designed to ensure permanent weakness may, when pushed past their limit, produce legitimacy. Like in finance, where stability breeds risk until collapse, in conflict humanitarian pressure can breed control until it produces its opposite — the unintended elevation of the very actors it sought to erase.

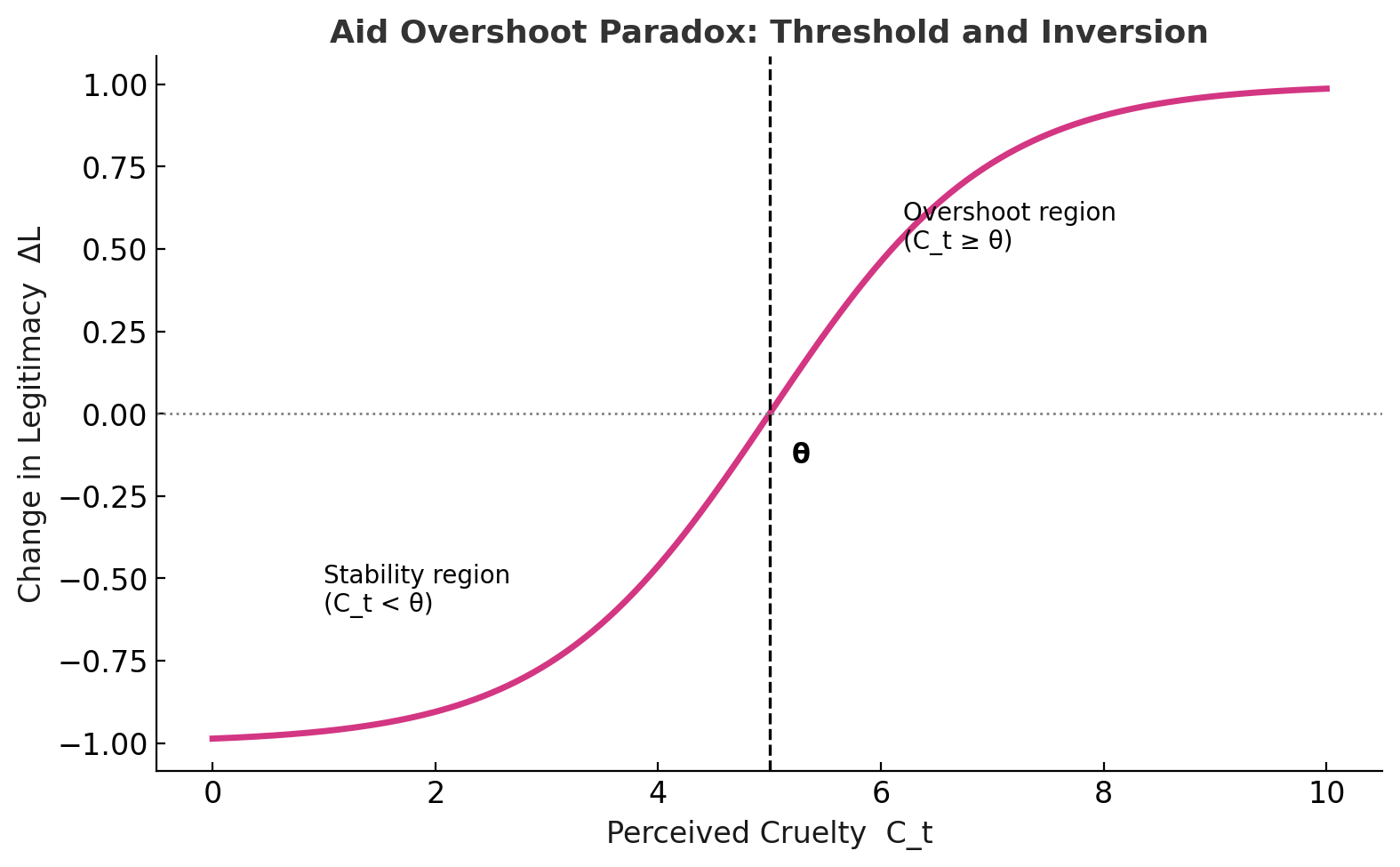

I call this the Aid Overshoot Paradox. Aid flows, when tolerated or manipulated by a dominant actor, can initially serve as an instrument of control. Civilians survive, the weaker faction remains dependent, and stability — though fragile — persists. The very presence of aid suppresses the ability of marginalized actors to claim legitimacy: they endure but do not thrive.

📊 Aid Overshoot Paradox: Threshold Dynamics (Perceived Cruelty vs Change in Legitimacy)

Formalization. Let us define the core variables:

- At = humanitarian aid at time t

- Pt = pressure/control exerted by the dominant actor

- Vt = visibility of that pressure to external audiences

- Ct = perceived cruelty at time t (a function of Pt and Vt)

- Dt = dependence of the weaker faction

- Lt = legitimacy of the weaker faction

- θ = threshold beyond which cruelty becomes counterproductive

- L* = legitimacy level at which external recognition occurs

Compact representation of the dynamics:

C_t = P_t × V_t (cruelty as perceived, scaled by visibility)

D_{t+1} = φ D_t + a A_t − ℓ L_t (aid raises dependence; legitimacy erodes it)

ΔL_{t+1} =

-λ A_t + ε, if C_t < θ (aid stabilizes, legitimacy suppressed)

γ (C_t − θ) + η A_t, if C_t ≥ θ (overshoot → legitimacy gain)

Recognition event:

R_t = 1{ L_t ≥ L* } (acknowledgment once legitimacy crosses threshold)

The paradox shows how aid sustains dependence until perceived cruelty (C_t) crosses a threshold (θ). Below θ, legitimacy is suppressed and control holds. Once θ is breached, the mechanism inverts: excessive visibility of cruelty realigns sympathy, and legitimacy rises instead of being contained.

- x-axis: Perceived Cruelty (C_t) — how strongly external audiences register the dominant actor’s pressure

- y-axis: Change in Legitimacy (ΔL) — whether the weaker actor’s legitimacy declines (negative) or grows (positive)

As Sollenberg (2012) shows, foreign aid only raises conflict when it crosses certain volumes and in context of weak institutions.

Aid in conflict zones is never just aid.

- To civilians, it is survival.

- To marginalized groups, it can be fuel.

- To dominant actors, it may become a lever — sustaining an adversary just long enough to frame them as beyond repair.

Yet even levers have limits. Push too far, and what once reinforced control can invert into recognition. The tipping point, like a financial collapse, arrives not gradually but suddenly — the moment strategy overshoots its bounds.

This is the dilemma: relief cannot escape the logic of strategy, and strategy cannot escape the risk of overshoot. Humanitarian aid sits between the two, at once a lifeline and a liability.

At the end of the day, each of us practices strategic thinking in our own lives — anticipating others’ actions, preparing contingencies, weighing short-term trade-offs against long-term outcomes. It should not surprise us that global leaders, confronted with war and humanitarian crises, do the same. But it should remind us of something else too: even the best strategy, if pushed past its limit, may turn against its maker.

The question we too rarely ask is simple but unsettling: when we deliver humanitarian aid, do we actually help — or do we sometimes make things worse?

The paradox suggests a different way of structuring oversight. Instead of asking only “does aid reach people in need?”, we must also ask “are the patterns of its obstruction remaining hidden?”

The PAVE Framework: Pattern – Access – Visibility – Escalation

Baseline Risk Conditions (always monitored)

Certain structural factors make manipulation more plausible. They do not prove wrongdoing, but they heighten the standard of oversight:

- Aid flows into a territory partly administered by an armed political actor.

- The package includes dual-use commodities such as fuel, cement, or telecoms.

- The recipient has a history of violent confrontation or recurring escalation cycles.

When these conditions exist, even small irregularities should be treated with caution.

PAVE Triggers

- Pattern: Are disruptions, fees, or reroutes recurring in a structured way? Recurrence suggests intentional shaping rather than chance.

- Access: Who actually receives aid or salaries? If distribution lists or vendors are effectively closed circuits, aid may entrench dependency.

- Visibility: Can outsiders verify last-mile delivery? If reporting is opaque, delayed, or reliant on actor-controlled systems, the risk of hidden manipulation grows.

- Escalation: Are there contextual signals of confrontation (rhetoric, training, fortification) rising in parallel with stable aid flows? If so, the paradox moves toward overshoot.

Traffic Light Heuristic

- Green: Isolated irregularities with clear explanations.

- Amber: One or more PAVE triggers recur in combination with baseline risks.

- Red: Selective access + opacity + escalation signals under baseline conditions → warning that aid may cross the overshoot threshold (θ).

When these triggers converge, risk stops being abstract. The figure below shows the sequence as it actually unfolds — from baseline irregularities, through recurring patterns, to the point where visibility pushes the system toward overshoot.

Visibility of dominant-actor pressure (V_t) rises over time. When baseline risk conditions exist, even isolated irregularities deserve scrutiny. Recurring triggers in the PAVE framework (Pattern, Access, Visibility, Escalation) mark the path toward escalation. Once the visibility threshold (θ) is crossed, perceived cruelty flips into legitimacy for the weaker actor. Policy guardrails (bottom bar) provide layered defenses to slow or reshape this path.

🔽 Click to Expand: Practical Implementation

How PAVE would flag risk early

P — Pattern (recurrence and structure)

What to check:

- Do transfers recur on a fixed cadence (e.g., monthly tranches) that normalize the armed actor’s fiscal base?

- Are there repeat bypasses around standard compliance (e.g., exemptions, ad hoc approvals) that gradually become the new normal?

- Do distinct streams (cash, fuel, payroll top-ups) co-move—i.e., when one expands, the others follow?

Why this raises alarm: a durable, predictable cash cadence can harden the actor’s operating budget (even if nominally civilian), freeing other revenue for coercive functions.

Tripwire (conceptual): if exceptions become the rule (e.g., a third consecutive “temporary” waiver), flag Amber.

A — Access (who actually benefits, who’s gated out)

What to check:

- Do the flows stabilize payrolls in admin bodies that the actor controls or heavily influences (education, municipal services, border posts)?

- Are procurement chains (fuel, cement, dual-use inputs) intermediated by entities linked to the actor’s economic networks?

- Are beneficiary lists and vendor rosters auditable and contestable, or are they effectively closed circuits?

Why this raises alarm: even if labeled “civilian,” control over access can convert funds into political loyalty and mobilization capacity (recruitment, surveillance, patronage).

Tripwire: if two or more major access points (payroll + key commodity) are controlled by the same actor’s ecosystem and there’s no independent contestability → Amber/Red.

V — Visibility (how legible the setup is to outsiders)

What to check:

- Can independent monitors trace the last mile (beneficiary identity, delivery confirmation) without relying on the actor’s own systems?

- Are fuel/electricity metered and published (even at aggregate), or are “technical” justifications used to keep flows opaque?

- Is there a time-lag between transfer and public reporting long enough to mask diversion?

Why this raises alarm: high Ct with low Vt = sub-threshold manipulation space.

Tripwire: if material flows scale up while reporting lags/opacity also increase → Amber, and if coupled with Pattern and Access red flags → Red.

E — Escalation (risk that the setup backfires into violence + legitimacy shock)

What to check:

- Are there capability-adjacent signals rising in parallel with funding (training tempo, procurement chatter, tunnel/fortification activity, rockets/drone testing frequency, cross-faction coordination)?

- Is the actor’s public rhetoric shifting toward confrontation while the fiscal base is becoming more secure?

- Are deterrence signals from the other side weakening because funding is expected to “stabilize” the actor?

Why this raises alarm: when capacity signals rise while a stabilized cash base persists under low visibility, the chance of a sudden kinetic inflection increases.

Tripwire: if two capacity-adjacent signals trend up and the other three PAVE buckets aren’t corrected → pre-θ warning (you can label this “Overshoot Risk”).

What would the alarm look like (before an attack)?

- Pattern: three consecutive tranches regularize liquidity → Amber.

- Access: payroll + key commodity vendors sit within the actor’s network, no contestability → Amber/Red.

- Visibility: monitoring relies on the actor’s own lists, metering absent, publication lag > one tranche → Amber.

- Escalation: observable capacity-adjacent signals tick up (e.g., training/test patterns, hardening) → pre-θ Overshoot Risk.

Net effect: Issue a formal early warning without alleging facts, stating: “Current configuration creates Overshoot Risk: recurrent funding + controlled access + low visibility + rising capacity signals.”

- Pattern Reviews, not Incident Logs: Oversight must assess whether irregularities repeat over time; recurrence is the true signal of manipulation.

- Visibility Safeguards: Donors should invest in mechanisms that shorten reporting lags and reduce reliance on data controlled by armed actors.

- Pre-Committed Escalation: Relief operations should define in advance how Amber → Red triggers prompt independent monitoring or escalation to international review bodies.

- Legitimacy Impact Reviews: Large aid packages should be evaluated not only for humanitarian outcomes but also for how they might alter perceptions of political legitimacy if manipulated.

Why This Matters

Existing approaches either stress program ethics (Do No Harm) or focus on overt starvation and siege tactics. PAVE addresses the gray zone in between: subtle manipulations tolerated because they remain hidden. By organizing oversight around Pattern, Access, Visibility, and Escalation, we can at least conceptually identify when aid flows are drifting toward the overshoot dynamic — and take corrective action before legitimacy flips.

If donors choose to maintain humanitarian flows under such conditions, restructure the pipeline so the same money is less usable for coercion and more visible:

- Two-key tranching: Each tranche auto-pauses unless both (i) independent last-mile verification and (ii) metered commodity reporting arrive on time.

- Ring-fencing via non-cash rails: Replace cash where feasible with tokenized vouchers or e-cards redeemable only at pre-cleared vendors, with anonymous but auditable spend categories.

- Third-party payroll attestation: Salary support requires independent headcount verification, rotating samples, and a challenge mechanism for contested names.

- Dual-use choke points: For fuel/cement/etc., require in-line metering + geo-fenced delivery windows; missing telemetry = automatic tranche deferral.

- Sunset & circuit breakers: Flows expire by default unless proactively renewed after a PAVE review; any Escalation flag trips a cool-off period.

- Visibility premiums: Donors pay a small top-up only when reporting quality improves (shorter lags, better granularity) — directly incentivizing Vt↑.

These design moves raise the θ-crossing cost for any actor tempted to weaponize aid, and they provide a defensible rationale if someone asks, “Why did you slow/reshape funding?”

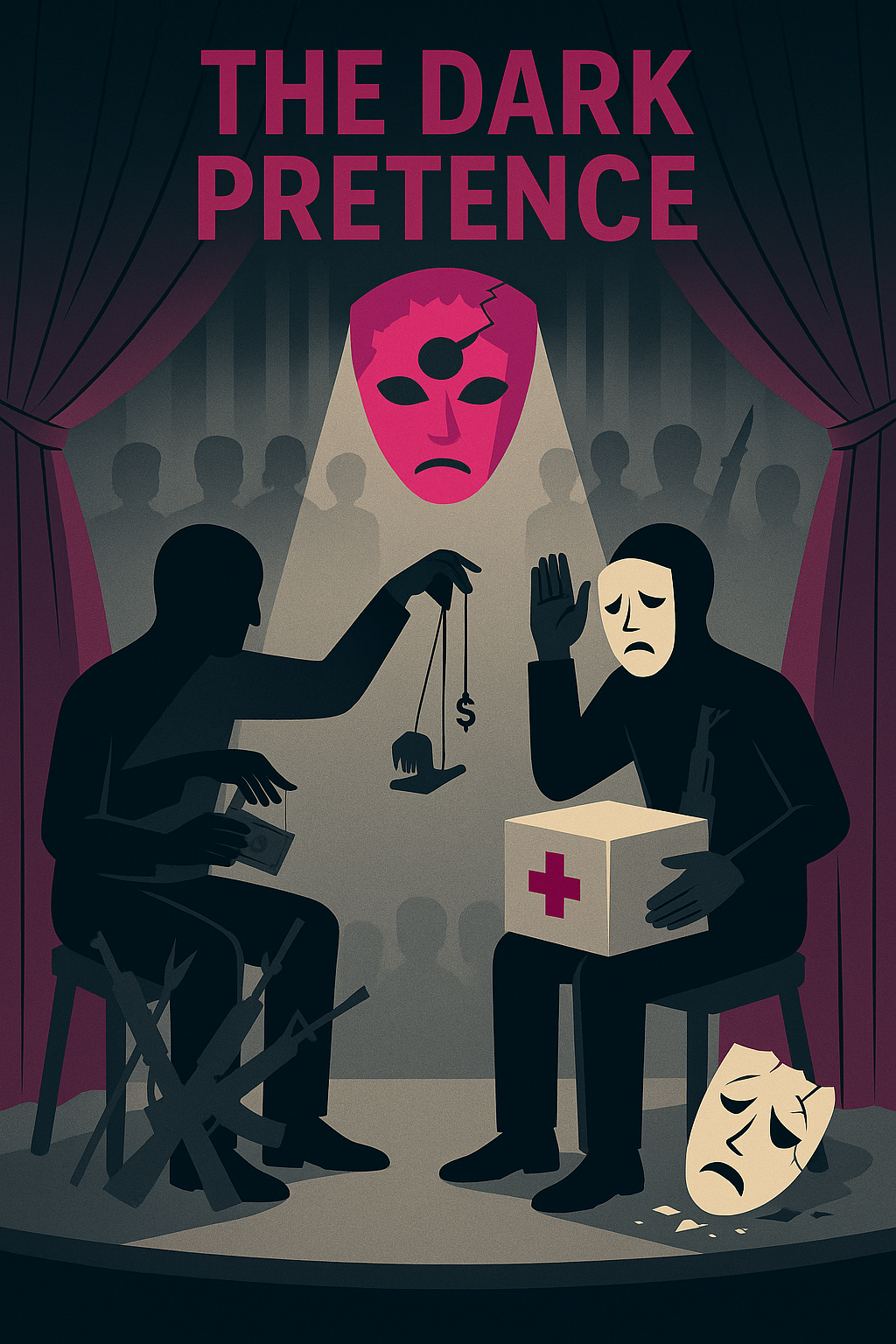

Appendix A — The Dark Pretence Game

A toy repeated-game formalization of the Aid Overshoot Paradox

Purpose. This appendix gives a clean, game-theoretic sketch of the logic in the article. It is deliberately spare (“toy”) but disciplined enough to communicate incentives, steady states, and policy levers. It is not case-specific and makes no empirical claims.

A. Players, timing, information

- Sponsor S (dominant state/donor consortium).

- Local Power L (armed political actor with partial administrative control).

- Discrete time t = 0,1,2,… with common discount factor δ ∈ (0,1).

- Public state each period: visibility Vₜ ≥ 0. There is a threshold θ > 0. When Vₜ ≥ θ, a legitimacy flip occurs (public, legal, diplomatic costs).

- Stage game is publicly observed; strategies are Markov in Vₜ. Equilibrium concept: Markov Perfect Equilibrium (MPE).

B. Moves and technology

In each period t:

Sponsor S chooses:

- aid intensity xₜ ∈ [0,1] (0 = block, 1 = generous flow),

- monitoring/visibility effort wₜ ∈ [0, w̄] (audits, access, transparency).

Local Power L chooses:

- manipulation mₜ ∈ [0,1] (0 = clean implementation; 1 = aggressive gatekeeping/diversion).

Visibility dynamics (one-state Markov)

Vₜ₊₁ = ρ·Vₜ + ϕ·mₜ − σ·wₜ + εₜ₊₁

Intuition: manipulation tends to surface (ϕ), monitoring suppresses/hastens legibility (σ), and memory decays (ρ).

C. Payoffs (reduced form)

Let 𝟙ₜ = 1 if Vₜ ≥ θ, else 0.

Sponsor S:

u_S = α·xₜ + β·xₜ·(1 − mₜ) − λ·wₜ − η·𝟙ₜ

Local Power L:

u_L = τ·xₜ·mₜ − κ·𝟙ₜ

Interpretation. S likes aid (stability, efficacy) but dislikes exposure and paying for monitoring; L likes capturing aid but dislikes exposure once visibility crosses θ.

D. Baseline Markov strategies

Pre-threshold trigger v̄ ∈ (0, θ):

Sponsor S: (xₜ, wₜ) = { (x̄, 0) if Vₜ < v̄ ; (x̱, w̄) if Vₜ ≥ v̄ } with 0 ≤ x̱ < x̄ ≤ 1

Interpretation: tolerate some manipulation when visibility is low; escalate monitoring and/or throttle aid when visibility nears θ.

Local Power L: mₜ = { m̄ if Vₜ < ṽ ; m̱ ≈ 0 if Vₜ ≥ ṽ } with 0 < m̱ < m̄ ≤ 1 and ṽ ∈ (0, θ)

E. Sub-threshold toleration (steady regime)

Δ(V) := E[Vₜ₊₁ − Vₜ | Vₜ = V] = (ρ − 1)·V + ϕ·m̄

If ρ ∈ (0,1), there is a unique fixed point V* = (ϕ·m̄)/(1 − ρ).

Proposition 1 (Managed manipulation). If V* < v̄ < θ and monitoring is sufficiently costly (λ ≫ η), there exists an MPE in which S plays (x̄,0) and L plays m̄ whenever Vₜ < v̄; Vₜ fluctuates around V* and remains sub-threshold with high probability absent shocks.

Sketch. Raising w below v̄ trades current λ for a small reduction in future V; as long as V* ≪ θ, gains are second-order. Cutting m below ṽ forgoes τ·x̄·m̄ now to reduce distant exposure risk; dominated for small V. ■

F. Overshoot and legitimacy flip

Let T_θ = inf { t ≥ 0 : Vₜ ≥ θ }.

Proposition 2 (Overshoot risk). Even under the managed regime, if shocks εₜ have unbounded right tail, or if L occasionally deviates to mₜ = m̄′ > m̄, then P(T_θ < ∞) > 0. When V_{T_θ} ≥ θ, both players suffer a discrete loss (η, κ), inducing a regime shift (e.g., S: w = w̄ and/or x = x̱; L: m ≈ 0).

Sketch. Shocks or transient escalations can push V above θ; payoff discontinuity at θ alters continuation values. ■

G. Pre-commitment and policy triggers

Sponsor trigger policy. Fix v̄ ∈ (0, θ) and commit that if Vₜ ≥ v̄, then (xₜ, wₜ) = (x̱, w̄) with σ·w̄ large enough that

E[Vₜ₊₁ − Vₜ | Vₜ = v̄] ≤ −δ_V < 0

Proposition 3 (Trigger deters drift). For any ε > 0, there exist v̄, w̄, x̱ such that the MPE under this trigger has P(T_θ < ∞) < ε.

Policy mapping.

- Two-key tranching & sunset/circuit breakers → credible (x̱, w̄) above v̄.

- Visibility premiums → subsidize w (raise σ/λ).

- Dual-use choke points → lower effective ϕ (metering, geo-fencing).

- Third-party payroll attestation → raises σ (faster legibility).

H. Comparative statics (qualitative)

- ϕ ↑ → V* ↑ → overshoot more likely.

- σ ↑ or λ ↓ → easier to keep V below v̄.

- η, κ ↑ → both prefer pre-threshold restraint (w ↑, m ↓).

- ρ ↑ → visibility lingers; shocks accumulate; risk rises.

- Var(ε) ↑ → rare overshoot even with “good” policies.

I. Operational early-warning (model-consistent)

V̂ₜ₊₁ = ρ·Vₜ + ϕ·m̂ₜ − σ·ŵₜ

Issue Amber if V̂ₜ₊ₖ ∈ [v̄, θ) for small k; Red if V̂ₜ₊ₖ ≥ θ. (Backbone of the traffic-light in the main text.)

J. What is testable (without numbers here)

- Patterned manipulation (m̂ ↑) with opaque reporting (ŵ ↓) predicts drift of V toward θ.

- Pre-committed triggers reduce manipulation near v̄ (selection effect).

- Visibility shocks (investigations, imagery) change policy (w ↑, x ↓) at first crossing.

K. Notation summary

x: aid intensity; w: monitoring effort; m: manipulation; V: visibility; θ: exposure threshold; parameters α, β, λ, η, τ, κ, ρ, ϕ, σ.

Model Explanation: Both sides tolerate a little hidden manipulation because it helps them now; but hidden things leak. Without early visibility, it overshoots—public sees it, legitimacy flips, everyone pays. Credible pre-threshold triggers and better visibility bend the path away from that cliff.

Appendix B — How the Model Applies Beyond the Hypothetical

Two case mappings: Sri Lanka/LTTE and Chechnya/Russia

Aim: To show how the variables in the paper’s toy model (A_t, P_t, V_t, C_t, L_t, \theta) and the PAVE triggers (Pattern–Access–Visibility–Escalation) appear in real conflicts—clearly separating what is documented from what is a reasonable inference.

B1. Sri Lanka vs. LTTE (2008–2009)

Documented facts

- Aid flows continued under state authorization. UN/WFP convoys delivered food into LTTE-held Vanni in late 2008–early 2009; OCHA situation reports tracked these authorized relief movements.

- Medical evacuations by sea occurred with government consent. ICRC ferries evacuated thousands of wounded and sick civilians from the conflict zone.

- Visibility of harm spiked late. UN and HRW documented repeated shelling near hospitals and large-scale civilian harm in “No Fire Zones,” which later drove international scrutiny (UN Panel of Experts, U.S. State Dept.).

Mapping to the model

- A_t (aid): Authorized WFP/UN convoys + ICRC evacuations (flows did not fully stop).

- P_t (pressure/control): State gatekeeping of corridors and internment/permissions; LTTE coercion and population control in the enclave.

- V_t (visibility): Initially low (restricted access, narrative control), then surging via NGO/UN reporting and global media in early–mid 2009.

- C_t (perceived cruelty): Rose with reporting on strikes near hospitals and denial of assistance.

- \theta (overshoot threshold) & L_t: As visibility of civilian harm increased, Colombo’s external legitimacy costs rose (UN inquiries, international criticism)—a plausible \theta crossing in the international arena even as the LTTE was militarily defeated.

PAVE in Sri Lanka

- Pattern: Recurrent, state-managed convoys; recurrent LTTE restrictions—regularized behaviors, not one-offs.

- Access: State controlled who/what moved; LTTE controlled distribution and exit of civilians.

- Visibility: Long periods of low verification → later visibility shocks via UN/ICRC/HRW.

- Escalation: Final offensive with heavy civilian tolls and ensuing global censure.

What is inference, not proven intent

- The record supports tolerated/structured aid and later legitimacy costs once cruelty became visible. It does not contain a public “smoking gun” that the state allowed aid as bait to entrap the LTTE; that step remains a strategic inference consistent with the observed pattern.

B2. Russia vs. Chechen Rebels (1994–1996; early 2000s)

Documented facts

- Humanitarian access was systematically instrumented. ICRC and other agencies faced denials/restrictions, notably around Samashki (April 1995); broader patterns of blocking and permissioning are well-documented.

- Visibility spiked episodically with atrocities. HRW, OSCE and others documented massacres/indiscriminate fire (e.g., Samashki), producing international criticism, though geopolitical insulation limited downstream policy shifts.

Mapping to the model

- A_t: Aid in and around Chechnya was irregular and often displaced to neighboring regions; access inside was frequently blocked—less a “tolerate to entrap” pattern, more access as leverage.

- P_t: High coercion (siege/bombardment) plus bureaucratic control over corridors and permissions.

- V_t: Often kept low; sharp spikes during major atrocities and independent investigations.

- C_t & \theta: Perceived cruelty rose with massacre documentation; partial legitimacy costs followed (EU/OSCE criticism), but evidence for a decisive global \theta crossing is weaker than in Sri Lanka.

PAVE in Chechnya

- Pattern: Repeated, centralized permissioning/denials.

- Access: State control of routes/timing; frequent confinement of aid to periphery.

- Visibility: Chronic opacity punctured by high-salience reports.

- Escalation: Large-scale offensives and urban destruction episodes.

What is inference, not proven intent

Evidence strongly supports access as an instrument and visibility-cost spikes; it is weaker on the specific “tolerate aid to keep rebels alive-but-weak, then entrap” mechanism. Treat that step as hypothesis rather than established fact for Chechnya.

Key sources (linked above):

- Sri Lanka: WFP/OCHA convoy reporting; ICRC/Lancet evacuations; HRW on hospital strikes; UN Panel of Experts (2011); OHCHR investigation.

- Chechnya: Watson Institute/ODI case study (Hansen & Seely); ICRC case on Samashki access denial; HRW reports (1995–1996); OSCE/UN reactions.